Near the beginning of my 1972 book Ingmar Bergman Directs, I wrote that “Ingmar Bergman is, in my most carefully considered opinion, the greatest filmmaker the world has seen so far.” Forty-six years later, I stand by that judgment. Bergman made about 50 feature films, as well as many television and radio programs. He staged several operas and ballets, and directed—and sometimes wrote—many theater productions. He was the author of books both autobiographical and fictional, not to mention various articles and speeches. But neither quantity nor diversity matters as much as quality and originality, in which his works abound.

Many of Bergman’s films received wide critical acclaim, and even his lesser achievements became objects of fascination and admiration during his lifetime. Whole new modes of filmmaking derived from Bergman, and the vast number of commentators on his works is very nearly equaled by those influenced by him, whether or not they know it. But the passage of time, the evolution of tastes, and our cultural emphasis on the new has meant that today’s young American moviegoers are unfamiliar with the Swedish filmmaker’s work. Even true cinephiles under the age of, say, 40 may never have seen one of his pictures. So Bergman’s centenary—he was born on July 14, 1918—provides a good occasion to introduce his work to new generations of viewers, with a brief overview of his career and a few suggestions for films that could serve as points of entry.

Bergman’s films often revel in extremes—sometimes intimate, sometimes harrowing—about almost-happy families or love affairs that break up. Consider his early film Summer Interlude (a title more accurately rendered Summerplay). In this 1951 movie, a ballerina, Marie, is rehearsing for a production of Swan Lake when she receives an old diary of hers. Reading it, she recollects a summer she spent years earlier as a teenager on a lovely island in the Stockholm archipelago. Henrik, her young lover that summer, dives into shallow water and dies of a broken neck in Marie’s arms. Back in the present, Marie has a new lover, David, with whom she quarrels, but they make up and she dances the lead in the ballet. For quite a while, Bergman called this film, with its meditations on love and loss, his favorite.

The English titles inflicted on Bergman’s films for commercial purposes sometimes distort and confuse. So A Passion becomes The Passion of Anna, even if it is more the passion of her lover Andreas and the implied passion is more Christ-like than physical. In America we got The Naked Night for what the British call Sawdust and Tinsel and the Swedish something like The Clown’s Evening. This, from 1953, was Bergman’s first true masterpiece. The story contrasts the ways of the circus with those of the theater, and contrasts strength (the circus owner and earthy ringmaster) with subtlety (the snotty actor and grandiose theater director).

At the center of the story are three women: the errant but loving wife of the clown; the solid but unexciting wife of the circus owner, who won’t take him back after he leaves her; and the flamboyant equestrienne mistress of the circus owner who gets involved with the arrogant theater star and occasions a spectacular fight between the men on the sand of the arena. The way their relationships play out establishes the conflict between quasi-superior, condescending art and besieged but resisting reality.

The film is a fine example of Bergman’s love for, or at least preoccupation with, women and their ways. It also shows that he was not just an expert teller of complex stories but a great stylist as well, able to bring psychological insight and highly telling detail into the plot.

Equally important in Bergman’s oeuvre is the human face; he uses faces in eloquent, sometimes sublime, close-ups to tell much of the story. Thus in what is called in English The Magician but in Swedish The Face, we get a plot that largely concerns the importance of mask or disguise versus bare reality—their fraught interaction and troubled, troubling coexistence. We also get faces in confrontation, in marvelously probing close-up. The wonder of how faces matter, often in mirrors, always revelatory of the inner being, truly carries the story. This is why, unlike with the work of lesser filmmakers, conventional synopsis often doesn’t suffice with Bergman’s films.

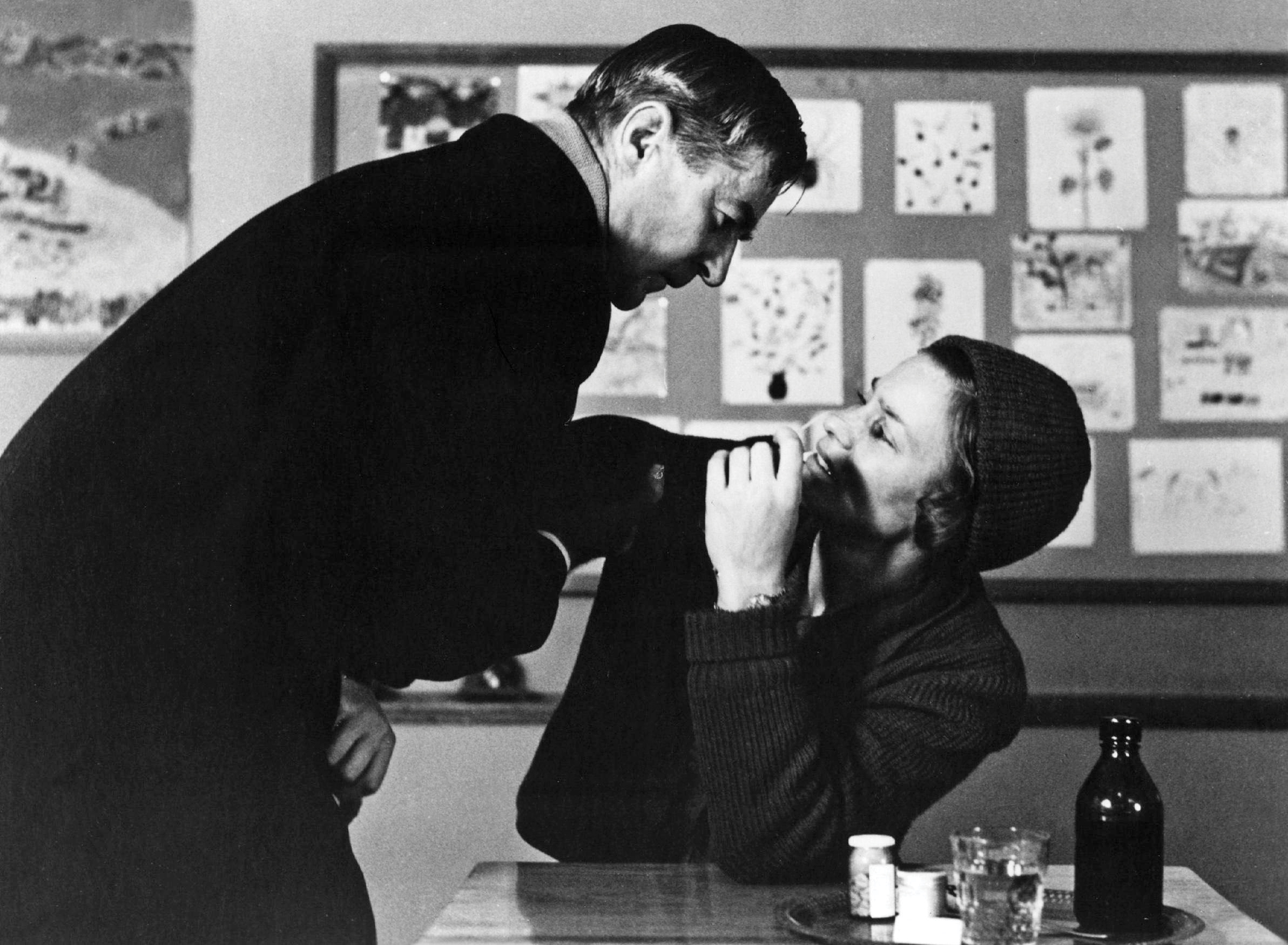

Bergman’s work profited immensely from his having at his disposal the actors and actresses of the Dramaten, Sweden’s Royal Dramatic Theater. They were recurring cast members in his films, appearing in roles in which they were wonderfully diverse yet somehow also affectingly familiar. They are as good-looking as they are talented, often conveying story with searching expressions that mutely speak for themselves.

Consider the 1963 film that would eventually become Bergman’s favorite, the only one that fulfilled everything he wanted to achieve, Winter Light. (In this case, the title change—from The Communicants in Swedish—was wise, since Lutheran ritual and practice are much less resonant in America.) The pale, exquisitely lighted wintry exteriors and interiors, and the chilling implied feelings, are all superbly shot by Sven Nykvist, Ingmar’s final, and probably greatest, cinematographer.

This is one of Bergman’s chamber films, with minimal cast. The widowed pastor Tomas suffers from both a bad flu and from personal coldness toward his parishioners, including his loving mistress, the schoolteacher Märta, whose solicitude merely irritates him. Tomas is conflicted by his memories in viewing old photographs of his dead wife and by his discovery of an old letter from Märta in which she declared her boundless love for him. He is unable to bring peace to a deeply depressed fisherman, Jonas, who commits suicide.

Tomas confronts Märta cruelly—yet he still asks her to accompany him on the drive to another, fairly distant church where it is his duty to hold a service again in the afternoon. On the way, they stop to tell Jonas’s pregnant wife about his death and are impressed by her stalwartness. Before the service at the afternoon church, the hunchbacked sexton, Frövik, tells Tomas that he has realized from the Gospels that Christ’s greatest torture, the real passion, was one he too has endured: that of not being understood by anyone, including God. The greatest agony is not being answered by man or God, the terrible understanding that no one has understood you. But God’s silence must be endured.

The afternoon service is totally unattended and Tomas could skip it, but he doesn’t; he celebrates with “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, the whole earth is full of His glory,” while Märta, kneeling in a pew, prays for their future shared happiness.

The close-ups of Ingrid Thulin as Märta are among the most inspired ever put to film, thanks to the efforts of the director, cinematographer, and actress. The work is a moving tribute to the faith of Bergman’s stern Lutheran minister father, particularly so because by that time the writer-director had given up the God and religion with which he had so long struggled.

Beyond his intense love of women and his unequaled filming of the face, it is worth making three further notes in passing. First, Bergman’s identification with every single one of his characters and their distinctive psychological problems shines through his work. Second, also evident is his respect for other directors, such as Fellini and several earlier Swedish ones, from whom he was not ashamed to learn. Finally, even though music is used very sparingly in Bergman’s films, it is worth mentioning that he loved classical music, from Bach to Bartók and beyond, and its influence can be detected in the way he directed—including his use of a sonata-like form and various musical devices.

The films I’ve described here should serve as a good entrée to Bergman’s work. I have concentrated on less obvious films, though I have unstinting admiration for the more popular ones: The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries (which should be The Strawberry Patch), and that impeccable, profound comedy, Smiles of a Summer Night, to which the 1973 Sondheim musical A Little Night Music pays sincere but diminishing tribute.

I have also omitted discussions of Persona, A Passion, and Scenes from a Marriage, complex masterpieces requiring elaborate analysis. And I have bypassed films that I find less thrilling, such as Hour of the Wolf, The Silence, and Cries and Whispers, although even those contain admirable passages.

Excellent video versions of many of Bergman’s movies—chiefly put out by the Criterion Collection—are readily available for purchase. And any questions you may have about him are handily dealt with in Birgitta Steene’s magnificent, omniscient Ingmar Bergman: A Reference Guide. Filled with all kinds of rewarding insight, it clocks in at 1,150 pages, the sort of thing not elicited by most other filmmakers. Doesn’t that in itself make a statement?