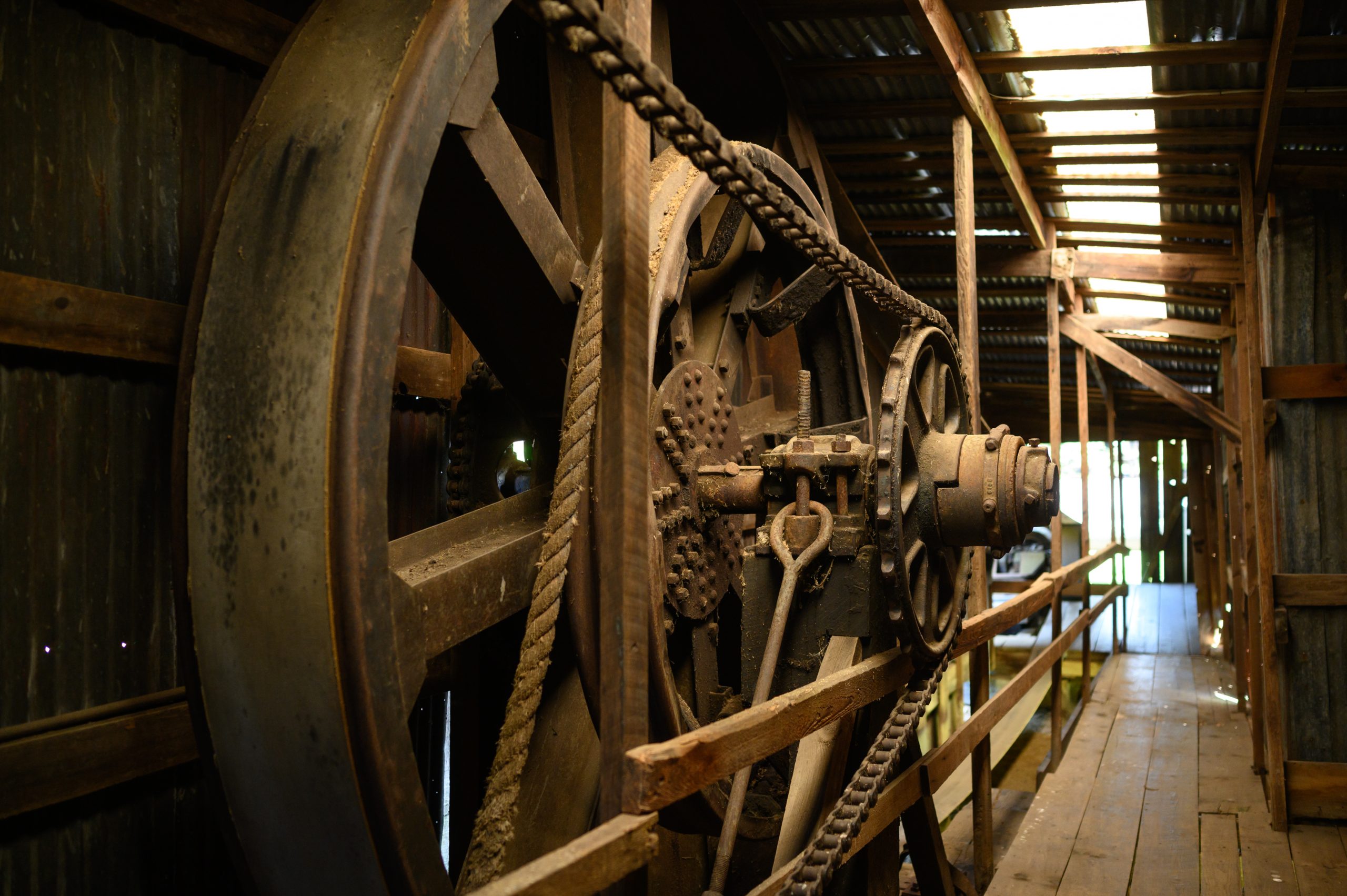

TITUSVILLE, Pennsylvania — In the valley that changed the world, all of the derricks are long gone. But the economic, environmental, and societal effect of Edwin Drake’s oil strike here in 1859 is still being felt today 162 years later.

What set Drake apart from previous oil discoveries was his work here proved petroleum could be produced in large quantities by drilling wells rather than by boiling the oil off of shale rock. That moment marked the beginning of the modern petroleum industry.

What happened here changed the world, taking us from a nation lit by tallow candles, preventing us from working after the sun set, and massively improving our transportation going from the limitations of the horse and cart to soaring in the skies above the earth.

Back then, care of the environment in pursuit of oil was not a priority, and the land suffered. Trees were cut down to make the derricks, and then the shanties for the workers resulted in soil erosion that turned the area into a sea of mud.

Heavy smoke hung in the valley from the refineries, and trains carried supplies and product up and down both sides of the creek, spilling oil and often setting the waterways afire in its path.

Outside of the spacious grounds of the Drake Well Oil Museum, there is scant evidence of the wildcat days of the discovery. The spruce, maple, and locust trees filling the rolling hills are lush. The creek is pristine and filled with trout, and the industry, which became organized in 1919 as the American Petroleum Institute, whose stated mission is not only to advocate for the industry’s economic interests and its workers but also to conserve the land the oil is extracted from.

That doesn’t mean the environmentalist movement will yield the organization any quarter.

API’s President and CEO Mike Sommers sat down with the Washington Examiner recently to outline what he believes could be common ground between the industry and the Biden administration and where there will likely be challenges.

Washington Examiner: Your first thoughts out of the gate of President Biden’s executive orders that shuts down the Keystone XL pipeline

Sommers: Of course, we’ve been really concerned about some of the initial policies that Biden put forward. Shutting down the Keystone XL pipeline killed about 11,000 union jobs on Day One. And then, on top of that, the ban on new leasing on federal lands, which could have a dramatic effect long-term in terms of the potential job loss. We did a big study on what that meant in late September last year, and we’ve been working hard to get that message out over the course of the last two weeks.

I do think the important component of what we see in the first few weeks of this administration is, their priority, of course, is climate change, but nothing that they’ve done would do one thing to improve over our position on climate change.

In fact, we would argue that what they’ve done would actually be a great detriment to our environment. And I would start with the Keystone XL pipeline. Most of those products from Canada are still going to come to the United States.

Pipelines are the safest, most responsible, most environmentally safe way to move these products, not putting them on trains or on the American interstates.

So, that actually did nothing to affect our climate footprint by any means. And then cutting off leasing on federal lands actually would have the opposite effect of helping us address climate change.

All that would mean is that we’re importing more products of these products from overseas, which do not have the same environmental regulations, one of the best producers in the world like the United States has. So, what they’re trying to do is, they’re trying to cut off the American supply of oil and gas. What they’re not doing is, they’re not doing anything on the demand side because we know that the world’s going to continue to consume millions of millions of barrels of oil every single day and, of course, continue to use natural gas in their homes and their businesses.

So we’re very concerned about the direction that this administration is pursuing because it’s not good for the climate, it’s not good for American industries, and it’s certainly not good for American jobs.

Washington Examiner: The criticism of your industry is that you don’t care about the environment. Explain what, if any, measures you take to protect it.

Sommers: One thing people don’t know about API is that, first of all, it is an advocacy organization. We advocate for the oil and gas industry in the United States. But in addition to that, more than half of what API does is, it’s the global standard-setter for the oil and gas industry. We set standards that the industry adheres to. In fact, we maintain over 700 industry standards, all in the area of health, environment, and safety.

We use these standards to really enforce what our principles are, that we produce in the most environmentally responsible way and better than any other country in the world. It is part and parcel of this industry. Safety is at our core, and environmental protection is at our core.

When I first joined API, I went to see one of our off-shore drilling facilities in the Gulf of Mexico, and this old petroleum engineer walks up to me, and he says to me, “Hey, you’re the new president of API?” And I said yes. And he said, “I want to thank you.” I said, “Thank me, for what?” And he said, “Thanks for keeping us safe.”

And it struck me at that moment that for most of the people who work in this industry, they don’t know API for … the advocacy that we do on Capitol Hill and in the states, but actually for the safety standards that we maintain. So, everybody who grows up in this industry, they don’t think of API as the American Petroleum Institute. They think of the API standard that they’re expected to adhere to in the development of oil and gas. And that’s a great point of pride for the organization and the industry.

A lot of those standards are actually written into both a state and federal law, that even though they don’t want to set the regulatory standard, they just mandate that the API standard is put in place.

But in addition to that, we have another program. We call it the environmental partnership. That was founded four years ago. That’s all about reducing methane emissions in our operations. So this is a program on top of the regulatory regime that’s already in place at the state and the federal level, where we bring together large producers and small producers to talk about best practices on reducing methane emissions.

It’s not something the government told us to do. That is something that we built as an industry association to make sure that our members were adhering to high-level environmental standards as well. It’s not in our interest for these products to be leaked. We want to sell those products into the marketplace. So we’re working overtime to make sure that we’re keeping those products in the pipe and delivering them to the marketplace.

Washington Examiner: If that is the case, what is the end goal for Biden and his environmental justice movement?

Sommers: Nothing that they’ve done so far is going to do anything but actually worsen our environmental performance. Because what they have actually pursued in the first four weeks of this administration has really been what we call an “import more oil” policy.

We are obviously going to continue to use oil and natural gas because we need it, and every outside expert says that, for as far as we can see, we’re going to be using a lot of these products. So the question really, I think for anyone, is going to be to point forward, whether we’re going to be getting those products from the United States with American workers and American environmental standards, or whether we are going to be getting them from regimes that are hostile to American interests with fewer environmental standards.

And that is the question that I think that policymakers have to answer. I’ll point you to one statistic that I think is just fascinating. Before the pandemic, the world was consuming 100 million barrels of oil every single day. 100 million barrels. During the worst part of the pandemic, when the world economy was basically shut down, the world was still consuming 81 million barrels every single day. So I think that points to, that this industry is not going anywhere. They shut down the whole world economy there for a few months, and the world was still consuming almost 80 million barrels of oil every single day. So I think there’s an incredible staying power for the industry, and I think this is just a question of whether you want to go back to the days of being dependent on OPEC, or dependent on Russia for oil and gas, or whether you want to produce it in the United States with American workers. And it’s unfortunate we’re at the position that we are today as a consequence of, I think, some energy illiteracy that has permeated Washington, D.C.

Washington Examiner: The oil will still get here with or without the pipeline, correct?

Sommers: First of all, there already is a Keystone Pipeline that, thanks to the Trump administration, they actually expanded capacity for that pipeline to carry more product. And there are other pipelines that can be used. A lot of that product, the oil, from the Canadian oil fields, it’s going to end up on rail cars. So the reason why this oil is important is because American refineries are tooled in such a way where we take so-called heavy oil, and we refine it into products that we use. And the way refiners make money is they take this heavy oil, which a lot of people don’t like to use, they want the lighter, sweet oil, and they take that heavy oil and they refine it into gasoline or chemical products, et cetera.

There are other sources for that heavy oil. One perfect example would be Venezuela. So, that’s the other question, are refiners still going to need that heavy oil. Otherwise, they have to spend billions of dollars to change the models or their refineries. So they’re going to get it from sources that are the most competitive. We think we should be getting it from Canada, our No. 1 ally, not from regimes like Russia or Venezuela that also specialize in these heavy oil products.

Washington Examiner: Point out some of the things we use every day in our lives that come from the oil that you transport and produce and refine.

Sommers: We should start from the moment you wake up in the morning. Your alarm clock goes off, it’s probably made with plastic that’s been made from petrochemicals. You get up. You put your feet on the carpet, that carpet is a by-product of petroleum-based chemicals. You walk to the bathroom. You use a toothbrush, that toothbrush, and both the bristles and the toothbrush itself are made from petrochemicals.

You turn on your faucet, the pipes that go from your faucet to the water basin, those are made with petroleum products. You go down to your kitchen. You turn on the oven to make yourself an egg, that’s natural gas that you’re using to on your stovetop. You sit down on a plastic chair in your kitchen. That product is made from petroleum chemicals, petrochemicals. And then you put on makeup on your way to work. Many makeups are made with petroleum. You drive your car. All the plastics, the tires, everything but the metal, which is probably actually uses petroleum to make the steel as well, and the gasoline are all petroleum products. You can literally not go through your day, not even five minutes of your day, without using a petroleum-based product.

Your cellphone, the first thing you check when you wake up in the morning, is made from petroleum products.

Washington Examiner: How has your industry changed from those derricks that used to dot the hills of western Pennsylvania and all of the environmental carnage that came from that era?

Sommers: Look, the most important environmental accomplishment that this country has made in the last decade is that the United States now has the cleanest air that we’ve had in a generation. And it’s not because of the expansion of windmills and solar panels, it’s because of the fuel switch that has gone on, from coal to natural gas. Gas is 50% more clean than coal. Almost all of our environmental accomplishments are a consequence of the incredible discoveries of natural gas in the United States. And because we have such deep deposits of natural gas, the price of natural gas has gone down dramatically. And because of a market-based system, not one that was mandated by the federal government, we were able to make that fuel switch from coal to natural gas, which has led to incredible environmental accomplishments.

That’s not because of a government mandate. That’s not because we shut down coal. It is because the market made a determination that the world wanted cleaner fuel and less expensive natural gas. And that occurred because of a technological advancement where we can now both frack and horizontally drill, and we’re able to find more of the products under our feet. And we’re very proud of that environmental accomplishment. I would argue that the tracker in the Marcellus Shale has a greener job than just about any other so-called green job in the United States because of the incredible environmental accomplishments that we were able to achieve as a consequence of the natural gas revolution in the United States.

Washington Examiner: What are the capabilities of wind and solar in terms of providing energy?

Sommers: They represent a very small part of the energy mix. We’re an organization that believes in an all-of-the-above energy policy, and they should continue to grow. But the root question is, at the same time, we know the population is going up significantly. In fact, if the U.N. says the population is going to go up 50% by 2050, and at the same time, energy demand is going to go up 30% by 2050. We know that the world’s going to be demanding more energy because of population growth. And as more people reach the middle class, they’re going to be demanding more energy.

So the question isn’t whether we’re going to have wind and solar. We’re going to have wind and solar, but you’re also going to need natural gas, in particular, to back up wind and solar because they’re intermittent resources.

You have to have something that is around for when the wind doesn’t blow, and the sun doesn’t shine. So we know that you’re going to have to continue to use that natural gas, and if we think of the best place to get it, it is in the United States. So we know that their footprint is going to continue to expand, but I also think they’re going to have challenges as well. Solar will require a significant build-out of solar infrastructure, solar panels, and you’re already starting to see people start to reject the environmental footprint that solar is going to have because of how much land will be required. The same is true of wind. They’re going to be dealing with similar challenges that we’re facing right now. And I think we all have to recognize that if we don’t get a permanent process that’s good for all the gas and good for wind and solar, none of this infrastructure is going to be built out.

Natural gas has improved American environmental performance over the course of the last 20 years. There’s no comparison to any other power source. It was natural gas that led to our environmental performance improving. So, the United States has the abundance of natural gas, as you know, being in western Pennsylvania. In fact, we have more than we can use.

We want to export natural gas to the rest of the world through liquefied natural gas. So this is one area where we would like to work with Biden’s administration to advance that because what it will do is improve other countries’ environmental performance as well. If you’re India and three-quarters of your power currently comes from coal, it’s better for you to be using natural gas from an environmental perspective.

If you’re China, who’s building a coal plant every single week and gets two-thirds of their power from coal, it’s better for them to use natural gas. So we think that we can export American environmental progress to the rest of the world.

And we think that that’s an area of common ground that we can find with the Biden administration.

Washington Examiner: Do you have a seat at the table to discuss that common ground?

Sommers: I am assuming that we will. The first few weeks of a political new government is always a little bit rocky, and I know that they needed to do things to appease the environmental community on, within their first few weeks. But I’m also confident that, as time progresses, that they’re going to want this industry at the table because we’re the ones that understand how to improve both environmental performance and supply the energy that the world is going to continue to need. So maybe I’m being too optimistic, but we’re hopeful that as time goes on that we’re going to have a seat at the table to discuss these big issues.