When it comes to judging whether corporations are violating antitrust law, pricing isn’t the problem for Facebook, Google, or Amazon.

That widely-used benchmark for identifying monopolistic dominance of a particular market applies to none of today’s tech industry giants.

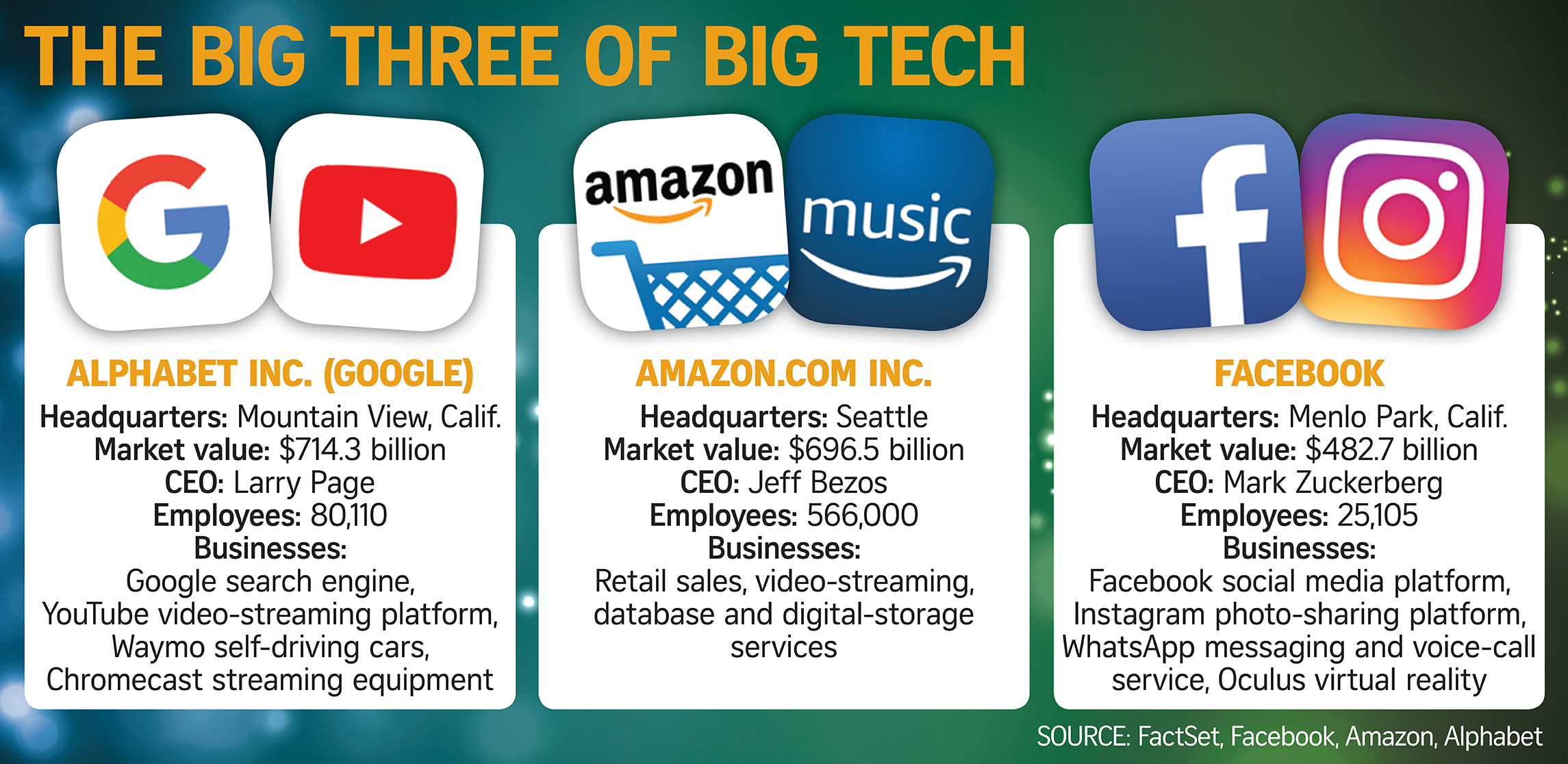

Facebook membership is free. Google, the top search engine on the Internet, charges nothing either, and e-retailer Amazon grew to its huge size by charging less for its wares than many brick-and-mortar companies.

But that won’t be enough to stop Congress from turning a scrutinizing eye on these icons of American innovation. Lawmakers grilled Mark Zuckerberg, the multibillionaire founder of Facebook, in two high-profile Capitol Hill hearings last week. That was mostly about privacy, although antitrust concerns were raised. And lawmakers, the Trump administration, and free-market advocates who see the power of the tech giants are increasingly considering moves on that front.

Such advocates, including the so-called hipster antitrust movement who want to break up the companies, don’t cite the companies’ mammoth size as the driving reason to break them up, even though Google’s $718 billion market value makes it the largest publicly traded company in the U.S., and Amazon and Facebook are comfortably in the top 10.

[Related: Bernie Sanders: Trump is right, Amazon has gotten too big]

For the Open Markets Institute, which is fighting what it views as a growing trend toward monopolization in corporate America, the critical question is the tech giants’ control of platforms that give them a powerful advantage over business customers who are, at times, competitors. Facebook’s social media apps and Amazon’s e-commerce site are prime examples.

“We identify that as a conflict of interest,” said Kevin Carty, a researcher with the Open Markets Institute. “These tech companies own the platform at the same time that they have an interest” in beating competitors who also use that platform.

Addressing such issues may mean a change in how America defines anticompetitive behavior, an issue at the heart of laws intended to ensure that the country’s capitalist economy continues to run smoothly for the benefit of consumers. Such changes could well reverberate in industries far beyond technology and carry consequences of their own, especially as the Justice Department under President Trump moves to block problematic mergers rather than approve them with complicated restrictions on business dealings that are difficult to enforce.

Winning at Monopoly

The agency’s antitrust division in recent years “has investigated a number of behavioral decree violations, but has found it onerous to collect information or satisfy the exacting standards of proving contempt and seeking relief,” said Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim, who heads the unit. “We have a limited window into the day-to-day operations of business, and it is difficult to monitor and enforce granular commitments like nondiscrimination and information firewalls.”

Gauging the potential effects such shifts requires an understanding of the pivotal role that competition plays in market capitalism, ensuring that buyers are provided with the best possible goods at the lowest prices and that the producers who deliver them are rewarded.

Theoretically, as a competitive market’s efficiency increases, marginal revenue (the extra income from selling an additional item) will gradually be balanced out by the extra cost of producing that item.

Anticompetitive actions, whether by a group of companies forming a trust in which they agree to keep prices high, or by a single company cornering a market so it has a monopoly, impede that system, and ultimately harm consumers.

Children learn this in the Monopoly board game, in which players compete to buy property groups, each of which typically has two or three components.

Owning one property allows a player to charge rent when rivals land on it. Owning an entire group allows a player to double the rate, since he or she now has a monopoly on that neighborhood, as well as add houses and hotels that can push the costs up even more.

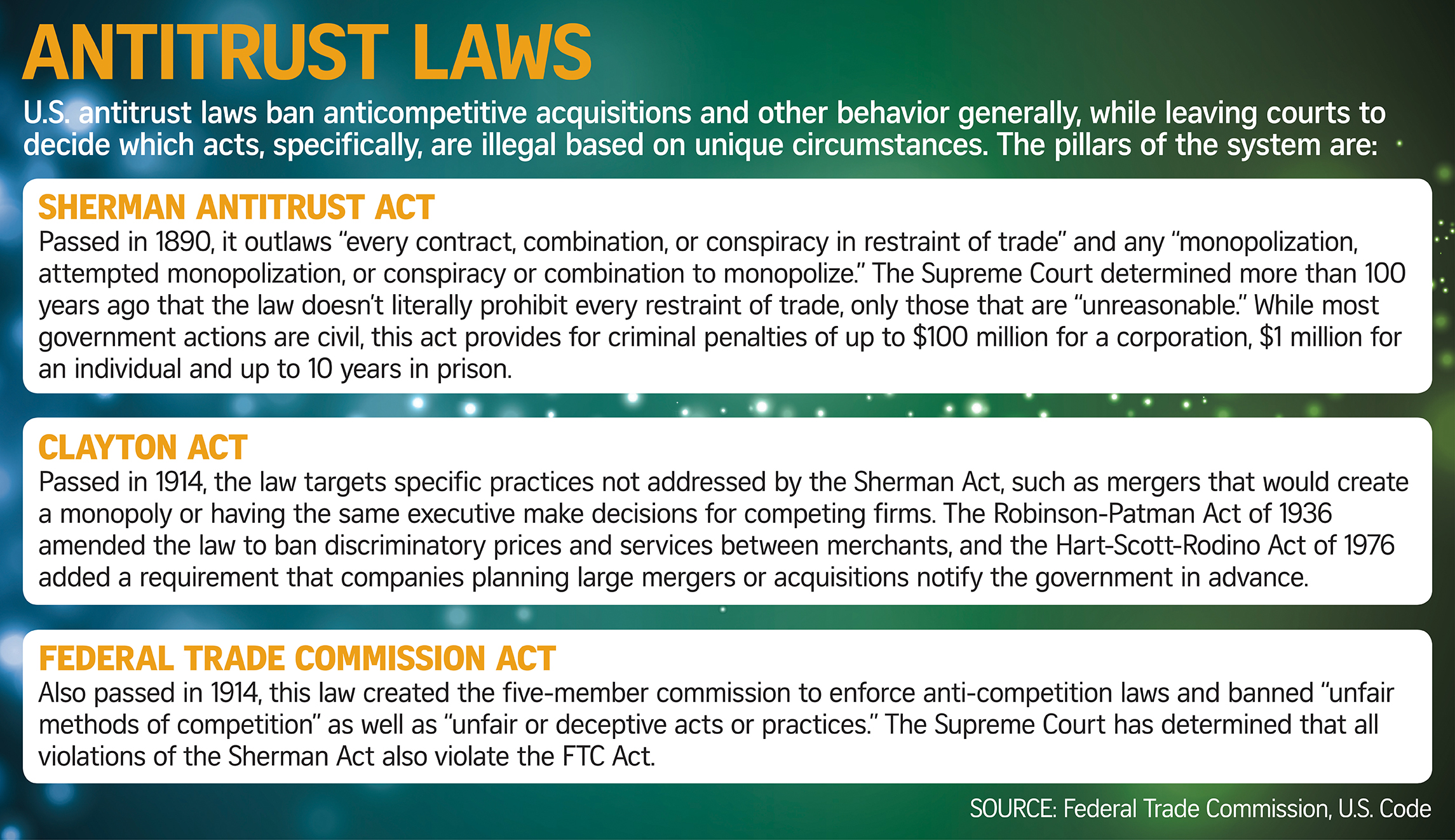

Antitrust rules that have been put in place by Congress over more than a century to prevent such anticompetitive behavior in the real world are all about economics, said George Cary, a Washington, D.C., partner at Cleary Gottlieb.

Formerly deputy director of the Federal Trade Commission’s competition bureau, Cary represented the agency in its successful challenge to the merger of Staples and Office Depot in 1997. At Cleary Gottlieb, he helped chemical firms Dow and DuPont win approval for a $130 billion all-stock combination of equals, completed in 2017.

AT&T’s Time Warner deal

Since the 1970s, such mergers have been viewed as anticompetitive by the federal government when they allow a company to control so much output that it can create artificial scarcity and force up prices, Cary explained at an American Constitution Society forum on antitrust laws.

“A lot of people were surprised that the Trump administration challenged” AT&T’s proposed takeover of Time Warner, he noted, but the issues it considered in making that decision had been the same as those that spurred the government to act in previous decades.

The administration is arguing in a trial that began in mid-March that the $108 billion deal would hurt competition, forcing consumers to pay more while slowing innovation in video programming and delivery.

AT&T, widely known for its landline and cellular telephone services, had already become the largest pay-television provider with its $67 billion purchase of satellite-service provider DIRECTV in 2015.

Adding Time Warner, which owns channels from HBO to CNN, would allow AT&T to charge its distribution rivals more for content such as HBO’s popular “Game of Thrones” series and college basketball’s March Madness, and also to slow down a shift toward so-called over-the-top video streaming, which can be less expensive than traditional cable television and facilitates “cord-cutting” by consumers.

It’s a classic example of a vertical merger, one in which a company buys another firm at a different point in the supply chain — think of an automaker buying a tire producer, for instance — rather than a horizontal merger, in which a business grows by acquiring a direct rival.

The risk posed by horizontal deals has often been gauged by the dominance of the combined company’s market share. While there is no “crisp black-and-white line,” controlling less than 30 percent is likely to be safe, while 50 percent or more invites considerable scrutiny, said David Balto, an antitrust lawyer in Washington.

Vertical integration

Congress has specified, however, that both horizontal and vertical mergers can violate antitrust law, the latter because it allows a company to control distribution of a component that its competitors need.

[Related: Trump ‘obsessed’ with regulating Amazon, wants to use antitrust laws: Report]

After buying Time Warner, AT&T “would likely use Turner’s important programming to hinder” competitors including video-streaming services, the Justice Department said in its suit, filed in federal court in D.C., seeking to block the deal.

“The merged firm would have the incentive and ability to charge more for Turner’s popular networks and take other actions to impede entrants that might otherwise threaten the merged firm’s high-profit, big-bundle, traditional pay-TV model,” the agency said.

That kind of vertical integration has also posed concerns about Big Tech. Google’s $12.5 billion purchase of mobile phone maker Motorola Mobility, which it sold two years later, is one example. Another is Amazon’s purchase of grocery chain Whole Foods for $13.7 billion last year, a move that sent shudders through the grocery industry.

At Facebook, meanwhile, takeovers of more direct competitors, such as photo-sharing service Instagram for $1 billion in 2012 and mobile-messaging company WhatsApp for $16 billion in 2014, have given the social media giant monopoly-like power, Scott Galloway, a professor at New York University’s Stern Business School, wrote in Esquire magazine’s March issue.

Facebook, along with Apple, Google parent Alphabet, and Amazon, should be forced to break up, he wrote, even though they haven’t “used their power to do the one thing that most economists would describe as the whole point of assembling a monopoly, which is to raise prices for consumers.”

Instead, the companies have exploited America’s traditional antipathy toward big government successfully enough that they’ve “led most of us to forget that competition — no less than private property, wage labor, voluntary exchange, and a price system — is one of the indispensable cylinders of the capitalist engine,” Galloway wrote.

Tech titans

“Their massive size and unchecked power have throttled competitive markets and kept the economy from doing its job — namely, to promote a vibrant middle class,” he wrote. Galloway, author of The Four, a book on the rise of the four tech giants, didn’t return messages seeking comment.

That the four titans received comparatively little scrutiny while amassing their present market heft illustrates the importance that has been given until now to the single issue of price when it comes to interpretations of antitrust law.

“One of the big shifts in the past few decades was that we decided that the single goal of antitrust should be to promote consumer welfare,” said Linda Khan, director of legal policy with the Open Markets Institute. “In practice, that has meant that enforcers look at short-term price effects and short-term outcome effects.”

Only fairly recently in the history of American capitalism did price and consumer welfare become the key issues for deciding whether corporate behavior was market-friendly or anti-competitive. Consumer welfare traces its primacy to the late 1970s and Robert Bork, the antitrust scholar and Reagan-era Supreme Court nominee.

But such a narrow focus can miss anticompetitive behavior that, for instance, operates not to raise prices but to quash potential rivals or stifle innovation, as the Trump administration says would happen if the AT&T merger with Time Warner were allowed.

Supreme Court interpretations of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1911, when the law was only two decades old, applied a “rule of reason” standard that held that the law barred any practices that imposed “an unreasonable or undue restraint” on trade.

One of those interpretations led to the breakup of Standard Oil Trust, the energy giant founded by John D. Rockefeller, that justices determined had worked with dozens of oil producers to inflate prices.

‘Unreasonable’ behavior

Still, Justice Louis Brandeis acknowledged in a 1912 speech to the Economic Club of New York that the standard left considerable uncertainty about what behaviors, specifically, were unreasonable, an ambiguity that would be left to future generations of lawyers to clarify.

Brandeis listed several anticompetitive tactics that had been used in his era to achieve monopolistic control. Among them were cutthroat competition, espionage, false claims of corporate independence, and the signing of exclusive contracts.

Those practices were “pursued not for the purpose of conducting a business in competition with others, but for the purpose of killing competitors,” he said.

“We learned long ago that liberty could be preserved only by limiting in some way the freedom of action of individuals; that otherwise, liberty would necessarily yield to absolutism,” Brandeis said. “In the same way, we have learned that unless there be regulation of competition, its excesses will lead to the destruction of competition, and monopoly will take its place.”

That’s precisely the risk posed by today’s tech giants, said Open Markets’ Carty. By selling its own wares on a platform that it controls, Amazon is competing with other retailers paying it to market their products on the site, he said.

Amazon’s market share is so big that it’s able to force its suppliers to offer prices low enough to undercut their own profits, Carty said. “The clearest example is book publishers,” he said. “They’re kind of the canary in the coal mine.”

Once Amazon had sufficient scale, it insisted on paying book publishers less, “a tactic we expect Amazon to use in a lot of other businesses,” Carty added.

News media and musicians

Google’s search engine, meanwhile, has given the Mountain View, Calif.-based company a decisive advantage in the advertising market, pulling money away from traditional media firms that depend on the search engine to reach prospective readers and viewers.

Menlo Park, Calif.-based Facebook not only enjoys an edge in advertising, but also controls how media firms’ content is distributed on its platform, a tool that many use to promote print and video.

“News organizations, musicians, and others have to really rely on this large platform owned by Facebook,” Carty said, “and Facebook is running that in favor of its own products as much as possible.”

While breaking up the firms, as Galloway proposes, is an obvious method of addressing such concerns, it’s not the only one. And Carty says it isn’t necessarily the best one either.

The U.S. has a long history of antitrust policy that has employed a variety of different remedies to address the problem of concentrated economic power, he said.

In the early 1900s, for instance, AT&T, then known as American Telephone & Telegraph, reached an agreement with the U.S. government, which had deemed it a monopoly, to forestall further legal action by selling the Western Union telegraph company, a former rival it had acquired.

That deal, known as the Kingsbury Commitment for its architect, Nathan Kingsbury, transformed AT&T into, primarily, a telephone company providing local and long-distance landline service.

Six more decades would pass before the company struck another deal with the government, divesting its local Bell telephone subsidiaries, which would become independent companies while the parent continued to provide long-distance service.

Other remedies include the Obama administration’s practice of consent decrees with companies proposing mergers, requiring guarantees that they will avoid anticompetitive behavior.

In 2011, for example, the Justice Department allowed the initial stage of a merger between cable-provider Comcast and entertainment company NBC Universal to move forward conditioned on the venture continuing to provide programming licenses to Comcast competitors.

Live Nation’s market edge

The Justice Department under Jeff Sessions, which favors structural remedies instead, is now reviewing the success or failure of efforts by the Obama Justice Department to control behavior with consent decrees.

An example is its approval of a merger of concert promoter Live Nation and ticket vendor Ticketmaster in 2010 which, according to the New York Times, the Justice Department has begun to investigate anew. Anschutz Entertainment Group, or AEG, the second-largest U.S. concert promoter, has told Justice that some venues have been threatened with the loss of valuable shows if they don’t use Ticketmaster, the Times said. (AEG is controlled by Philip Anschutz, proprietor of the

Washington Examiner.)

The Obama-era approach was “fundamentally regulatory,” Delrahim, the antitrust chief at Justice, said at an American Bar Association forum last fall.

He described it as “imposing ongoing government oversight on what should preferably be a free market.” The newer strategy, by contrast, conforms with Trump’s effort to curb unnecessary regulation, which the president views as hindering economic growth.

The structural measures it favors would have been appropriate with Facebook’s purchases of Instagram and WhatsApp, as well as Amazon’s Whole Foods deal, Carty suggested. Requiring spinoffs now could achieve a similar result.

Other measures to boost competition might include minimizing the data that Facebook is allowed to collect from users in order to target ads, or enacting laws that mandate portability for messaging network users, much as Congress did for medical providers in the early 2000s.

Very harsh remedy

If Twitter or Facebook users could move their whole networks to a different platform, seamlessly, neither platform would have its dominance guaranteed. And the government wouldn’t need day-to-day oversight of the platforms.

“I don’t think we’re even close to any kind of case that any of these companies need to be broken up,” said Balto, the antitrust lawyer. “Divestiture is a very, very harsh remedy and used extremely rarely in antitrust cases.”

Forcing one of the Big Tech firms to break itself up or even sell a subsidiary, might be construed as penalizing success, he argued.

“We don’t really want to say, ‘You can grow up, but you can only grow so large or otherwise, we’re going to punish you,’” Balto said. “We’re just light-years away from any kind of real case here that the size of these companies harms competition or that there’s a need to break them up or limit their size.”

Still, antitrust enforcement in its broadest sense is inherently deregulatory, argues Delrahim, citing a Depression-era predecessor who described its purpose as “an effort to avoid detailed government regulation of business by keeping competition in control of prices.”

Delrahim himself envisions continued emphasis on what Bork, the Yale University antitrust scholar and author of The Antitrust Paradox, described as “the single goal of consumer welfare in the interpretation of antitrust laws.”

While there’s a debate about whether the concept of consumer welfare could be expanded to cover metrics beyond price, that remains the easiest to measure, so it’s what law enforcement tends to look at, Khan said.

“We’ve adopted consumer welfare as a proxy for what competition is, but it fails to actually capture what competitive markets look like,” she said.

‘Doesn’t feel that way’

A bill proposed by Rep. Keith Ellison, a Minnesota Democrat, would address that by requiring the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice to undertake retrospective studies of how mergers affect not only prices but also jobs, wages, and local economies.

It’s backed by the Congressional Antitrust Caucus, formed by Rep. Ro Khanna, a California Democrat and cosponsor.

The caucus isn’t attempting to take a sledgehammer, big-is-bad approach, Khanna explained, acknowledging concerns like those of Consumer Technology Association President Gary Shapiro, who says tech companies’ size reflects the ubiquity of the Internet in modern life.

“An overly-interventionist position, which seeks to punish companies for their size rather than for their actual offenses, can impede our economic growth and reduce incentives for risk, creativity and entrepreneurialism,” Shapiro wrote in a blog post assessing the Trump administration’s nominees to lead the Federal Trade Commission. “More, it would hurt our national competitiveness. ”

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, meanwhile, pushed back against Sen. Lindsey Graham’s suggestion in last week’s hearing that the size of his company makes it a monopoly.

“It certainly doesn’t feel that way to me,” he said, citing firms such as Google and Apple that provide services similar to some of Facebook’s. “We have a lot of competitors.”

While voters have become frustrated, as shown in the 2016 election, with giant corporations they believe disregard their interests and a government they view as co-opted by business, Khanna said it’s still important to address such issues carefully.

“What we need to do is ask, ‘How do we encourage competition in ways that are thoughtful?” he said. It’s possible that Facebook’s purchase of Instagram, for instance, shouldn’t have been approved, but that would have come with risks of its own.

When regulators reject a deal like that, he said, “you provide a disincentive for startups to get funded,” since investors often do so with the hope that a startup will eventually be taken over, giving them a sizable return.

“Lots of the discussion isn’t, in my view, nuanced enough,” Khanna said, and reflexively deciding that size is undesirable isn’t “going to come to the right policy.”