Something like Newton’s Third Law—that every action has an equal and opposite reaction—holds in electoral politics. If one party finds a way to appeal to some new group of voters or win some new set of states, the other party finds a way to peel a different group away from their opponent’s coalition and keep things competitive. And if someone is at the right place at the right time, they can ride those shifts into political power.

Or, in former Minnesota governor Tim Pawlenty’s case, back into political power.

Pawlenty was governor from 2003 to 2011, briefly sought the 2012 GOP presidential nomination, and has been quiet since then. But last week, Pawlenty announced that he was running for governor of Minnesota again.

If Pawlenty wins the GOP nomination, he’ll face a redder and less politically weird Minnesota. And if he can leverage his political strengths, he stands a decent chance of pushing back on the national Democratic environment and winning his old job back.

Minnesota—Less Weird and Less Blue than 2002

A lot has changed in American politics since 2002, when Pawlenty won his first term as governor. That includes Minnesota.

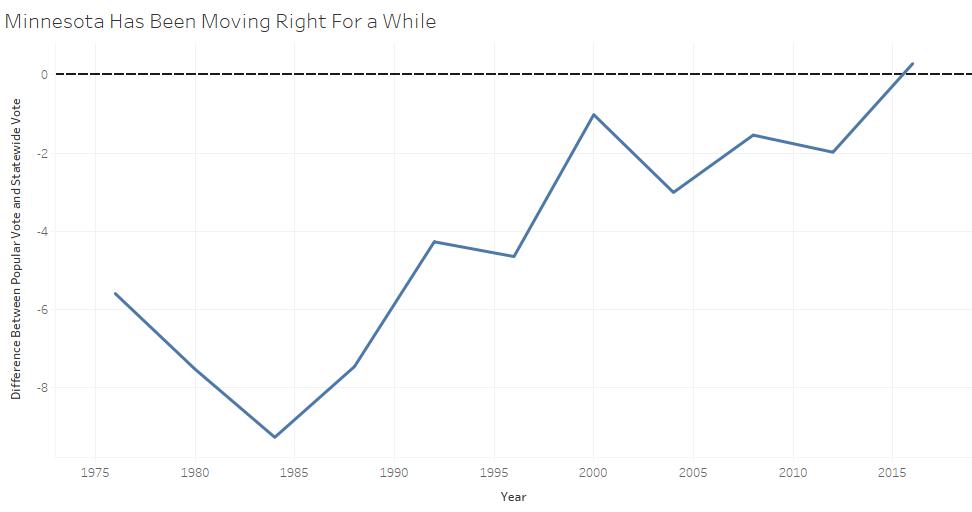

This chart shows the partisan lean of the state (Republican share of the two-party statewide vote compared to Republican share of the two-party popular vote in each presidential election since 1976). Positive numbers indicate a more Republican lean and negative numbers indicate a more Democratic lean relative to the country (the zero line is near the top of the graphic). While Democrats have been able to win Minnesota at the presidential level in every election since 1972, the margin has steadily shrunk. In 2016, Trump only lost the state by 1.5 points.

Minnesota’s rightward trend isn’t that simple though.

Part of it can be explained by the rural-urban trade that both parties have been engaging in for multiple cycles.

This .gif shows the short term trend—the difference between Romney and Trump precinct-level vote percentages. In the Minneapolis-St.Paul area (the dense cluster of precincts on the state’s inner curve) you see a blue expansion, and in the rest of the state (which is more rural) you see a big red expansion. The medium-term trend is similar.

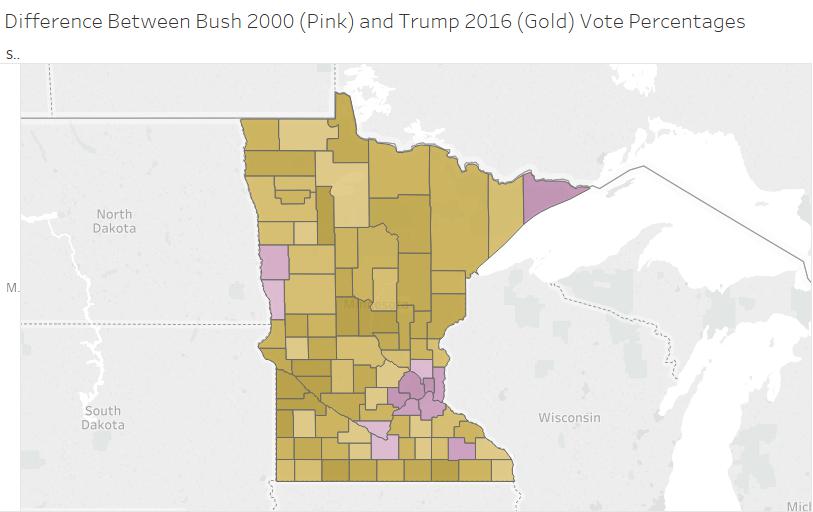

This map shows the difference between George W. Bush’s overall percentage of the vote and Trump’s percentage by county. Trump got a greater percentage of the vote in gold counties, and Bush got a greater percentage of the vote in pink counties. County-level results aren’t as granular as precinct-level results, but the same pattern shows up: Over time the GOP has lost some steam in larger metro areas and gained ground in rural areas. Trump won 67 percent, 61 percent, and 54 percent of the two-party vote in rural areas, small towns, and large towns respectively, while George W. Bush only won 55 percent, 54 percent, and 48 percent in those areas in 2000. Al Gore, on the other hand, only won 53.5 percent in the state’s major metro area (Minneapolis-St. Paul) while Hillary Clinton won 57.4 percent of the two-party vote there. That might not seem like it a big difference, but the broad Minneapolis area contains over half of the state’s two-party votes.

That asymmetry worked in the GOP’s favor and allowed them to continue to cut into Democratic margins. But this trade-off isn’t the whole story of Minnesota politics.

The North Star State really likes third party candidates. In both 1992 and 1996, Reform party candidate H. Ross Perot won a larger share of the vote in Minnesota than he did nationally. And after Perot left the political stage, the Reform party stuck around in Minnesota (where it’s now called the Independence party) and kept on fielding relatively successful candidates.

Most notably, in 1998, Jesse “The Body” Ventura beat Republican Norm Coleman and Democrat Skip Humphrey to become governor with only 37 percent of the vote. Ventura declined to run for re-election in 2002, but Tim Penny, an Independence party candidate, ran that year and took 16.2 percent of the vote (a very high number for a third party candidate).

That’s the environment Pawlenty was in when he won the governorship for the first time. He won in 2002 with only a 44 percent plurality, and he won again in 2006 with only 46.7 percent of the vote. The Independence party saw a drop-off in their vote percentage between 2002 and 2006 (they went down to 6.4 percent), but Democrats gained ground (going from 36.5 percent in 2002 to 45.7 percent in 2006) and both parties only lost a few percentage points of support between 2006 and 2010 (and the Independence party candidate got 12 percent of the vote), when Democrat Mark Dayton edged out Republican Tom Emmer for the governorship. Then, in 2014, Mark Dayton won re-election while the Independence party candidate was reduced to only three percent of the vote.

The Independence party also hasn’t performed particularly well in senate contests either. In 2008, former Sen. Dean Barkley won about 15 percent of the overall vote running as an Independence candidate, but other Independence or Reform candidates had trouble cracking double digits before or after that election.

So while the third party movement in Minnesota has been stronger than in other states, it seems to be at best inconsistent in its strength and at worst losing ground.

It’s still unclear exactly how strong the third party candidates for governor will be. But if they’re weak, that would again put Pawlenty in unfamiliar territory. Not only would the composition of his own party have changed, but he would be running a more normal gubernatorial race with only two major candidates. That said, it’s possible to imagine a good Republican candidate adapting to this new situation and managing a win.

So is Pawlenty a good candidate?

Candidate quality is an important and slippery part of most major elections, but it’s especially important in gubernatorial races. In Senate or House races, voters often rely on their views of the national-level parties to guide their vote, and many candidates don’t (or simply can’t) do much to move the needle. But gubernatorial elections aren’t so connected to national-level partisanship (see the Republican governor or Vermont or the Democratic governor of Montana), so it might be easier for an individual candidate to make a difference. And, given the national political conditions, Pawlenty might need to be a really solid candidate in order to win.

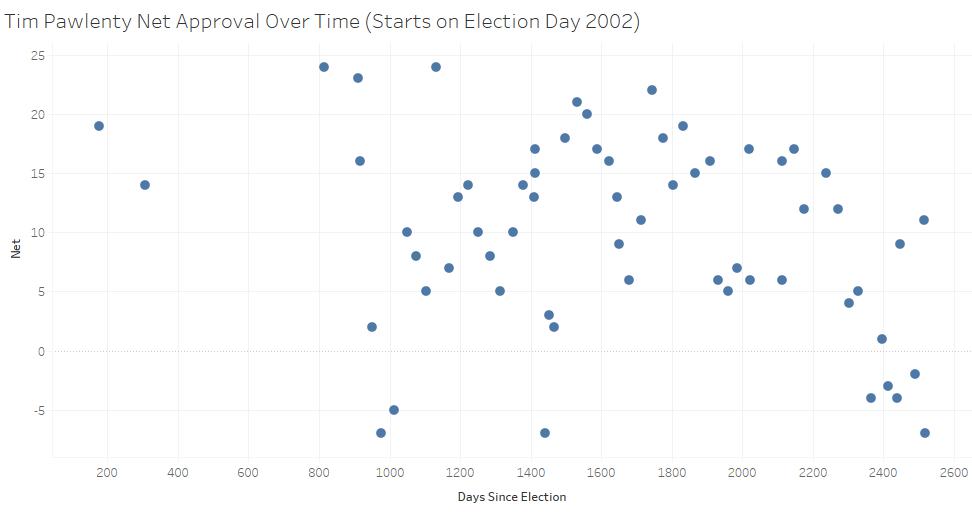

There’s some evidence that he could pull it off. During his two terms as governor, his approval ratings were generally positive

The polling dataset I used doesn’t track strong approval or disapproval, and it ends in 2009 (horizontal axis is days since the 2002 election). But the data I have suggests that most voters were happy with Pawlenty for most of his tenure. I don’t have data on how many voters strongly approved or disapproved of him, but it’s not hard to look at his 2012 presidential campaign and imagine that he didn’t inspire the same level of animosity or love that other politicians might have. And in an era when Donald Trump is the president, Pawlenty’s normalcy may be an advantage.

Maybe more importantly, he’s won the governorship twice before, so any personal baggage he has is likely already known. Political experience can also be helpful—someone who has won a governorship twice should be able to avoid some of the rookie mistakes that first time candidates often make.

But we shouldn’t get too carried away here. Pawlenty is neither Joe Manchin nor Susan Collins. He won both of his gubernatorial races with only a plurality of the vote, and in 2006 he barely beat an opponent who struggled in the final stretch of the campaign. His numbers started to sink towards the end of my time series (and may have continued to do so after my time series ended), and he has spent time as a bank lobbyist.

What are his chances of winning?

Our take away should be that Pawlenty is a good candidate who could win this race. He’s not the reincarnation of Ronald Reagan, but he doesn’t need to be. His entry into the field helps the GOP and might allow them to offset some probable Democratic gains elsewhere in the national gubernatorial map.

Sabato’s Crystal Ball, Cook Political Report and Governing all rate this race as a toss-up, and RealClearPolitics and Inside Elections rate it as “Leans Dem.” Until we get more polling, it’s worth thinking about the contest as something close to a 50-50 proposition, with maybe a slight edge given to the Democrats. That might sound like bad news for the GOP, but it’s not. Minnesota is a purple state, 2018 looks like it’ll be a blue year, and Democrats have a genuinely strong field—so marking this race as a toss-up or Leaning Democratic is actually a pretty good starting place for the GOP.