Peter Adderton, the Boost Mobile founder contesting Sprint’s merger with T-Mobile, has come up with a plan to counter some of the harm he believes it would cause to low-income consumers.

Adderton wants federal regulators to require the two cell-phone carriers to sell not only some of their prepaid-service businesses, whose low rates appeal to users with limited means, but about 40 percent of Sprint’s capacity in the 2.5-gigahertz band, which he would seek to buy for development of a prepaid broadband network capable of serving homes.

The new service would charge just $9.95 a month, he said, compared with the typical rate of about $80. It would be available only in certain areas, those where a post-merger T-Mobile would likely be competing with larger carriers like AT&T and Verizon and less focused on low-income customers.

There’s a market of people who want basic Internet service and can’t afford $80 a month, but whose resources aren’t limited enough to qualify for government assistance, Adderton said in an interview with the Washington Examiner.

They could, however, afford $9.95 a month, he added. “They have kids coming home from school and they’re getting a subsidized tutor from school, but they don’t have the ability to connect the two.”

Adderton, who started Boost Mobile in 2000 to cater to low-income markets, worries that T-Mobile’s $26.5 billion offer for Sprint, which now owns Boost in the U.S., is the beginning of the end for the brand as well as for MetroPCS, a key rival in the market for pre-paid services.

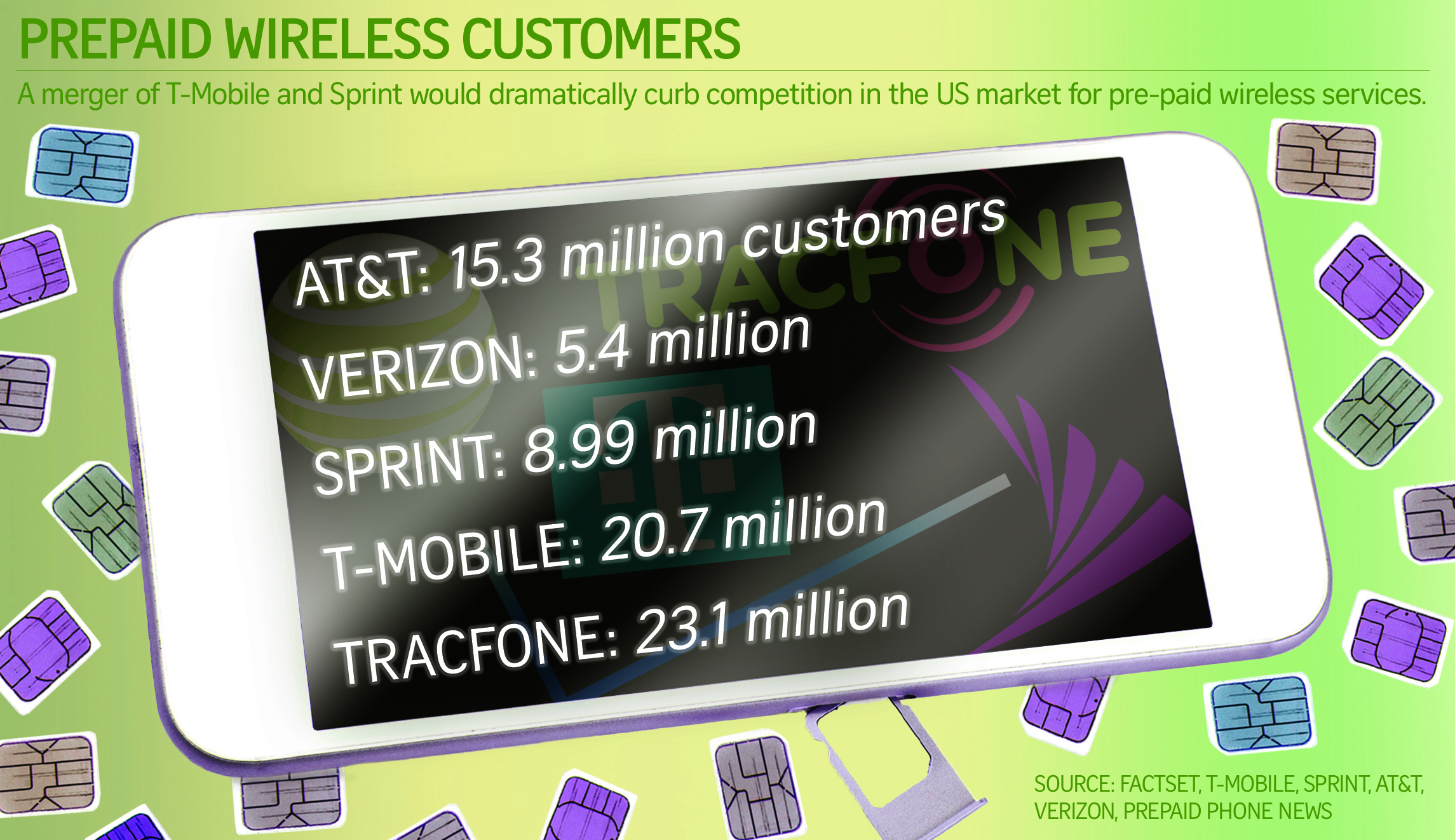

Boost, whose U.S. operations were taken over by Nextel Communications before its purchase by Sprint, and MetroPCS, which is owned by T-Mobile, join Sprint’s Virgin Mobile USA in commanding about 40 percent of the prepaid mobile-phone market, according to Adderton.

Losing the competition between those brands would mean escalating prices for some 30 million Americans who can least afford them, he says, and the damage would be worsened by T-Mobile’s focus on fifth-generation, or 5G, wireless broadband services, which would initially be affordable only to middle- and upper-income customers.

To get around those price barriers, Adderton’s proposed business would use cheaper 4G technology.

“The speeds they’re getting out of new technology and new encoders in these networks is pretty incredible,” he said.

“It’s absolutely enough speed to be able to provide the level of service and care that we would need,” even if it wouldn’t be suitable for streaming shows like HBO’s “Game of Thrones” onto the 60-inch television screens favored by more well-to-do Americans, he said.

And for lower-income consumers, even limited broadband, the umbrella term for high-speed Internet service, can be a game-changer.

A 2017 report by the Brookings Institution found the weakest broadband subscription rates in Census tracts with below-median incomes, a trend that reversed itself in higher-income areas.

“The discrepancies suggest that those being left behind by the transition are also those who were already struggling economically,” authors Adie Tomer, Elizabeth Kneebone and Ranjitha Shivaram concluded.

The effects of a T-Mobile merger on those communities aren’t a foregone conclusion, however.

T-Mobile Chief Excecutive Officer John Legere, has argued that his company’s takeover of Sprint will ultimately drive down prices by creating a firm large enough to compete with industry titans like AT&T, Verizon and Comcast.

“We’ll offer a real alternative and create competition for millions of Americans, many in under-served rural communities,” he said in an open letter detailing the merger, plans that he reiterated in a late June hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s panel on antitrust and competition policy.

“Make no mistake — even after the transaction, we will still be the little guy among these giants,” he said. “We won’t have an existing cable or fixed broadband base of customers to cross‐sell or other services to cross‐subsidize our network costs. That means we will still need to offer more value to consumers to get their attention.”

Consumer Action for a Strong Economy, a consumer organization that espouses free-market principles, said some of the merger’s payoff would come just from the creation of a company with the scale to take on Verizon and AT&T.

With Sprint’s capacity in higher-frequency bandwidth and T-Mobile’s in lower-frequency, “they really do stitch together” a complementary nationwide network, said Gerard Scimeca, the group’s vice president.

“What we’re getting is billions more in investment, another national carrier to compete with the two dominant ones, and we’re getting transformative technology that’s going to reshape pretty much everything,” he said. “The sooner that happens, the more people participating in that, the more competition, we all think that’s good, ultimately.”

But even if competition continues after the merger, the degree of it is critical for consumers who rely on prepaid plans, Sen. Amy Klobuchar, the panel’s highest-ranking Democrat, noted at the Senate hearing.

“Millions of Americans, particularly low-income Americans, depend on wireless networks for their primary connection to the Internet,” she said. “For 20 percent of Americans, that is the only way they get their home Internet access. It is essential that we have access to reliable wireless at fair, competitive rates.”