The coronavirus pandemic changed education in the United States forever. It cast a critical light on school financing, the ability of students, teachers, and parents to adapt to a new scholastic landscape, and gave teachers unions more power than they’ve had in a generation. In this series, Students Left Behind, the Washington Examiner takes a closer look at the toll the pandemic had on our nation’s public school system and the lessons learned along the way.

When second-grader Ethan Daniel was firing up his laptop for a long day of remote learning at Barrow Elementary School, his big brother JD, a seventh-grader at Athens Academy, was getting face-to-face instruction, interacting with classmates, and playing sports.

The two Georgia boys (one enrolled in a public school and the other in a private school) had completely different educational experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, with one child thriving and the other struggling.

“I have a very dramatic foil between the two of them,” their mother Susan Daniel told the Washington Examiner.

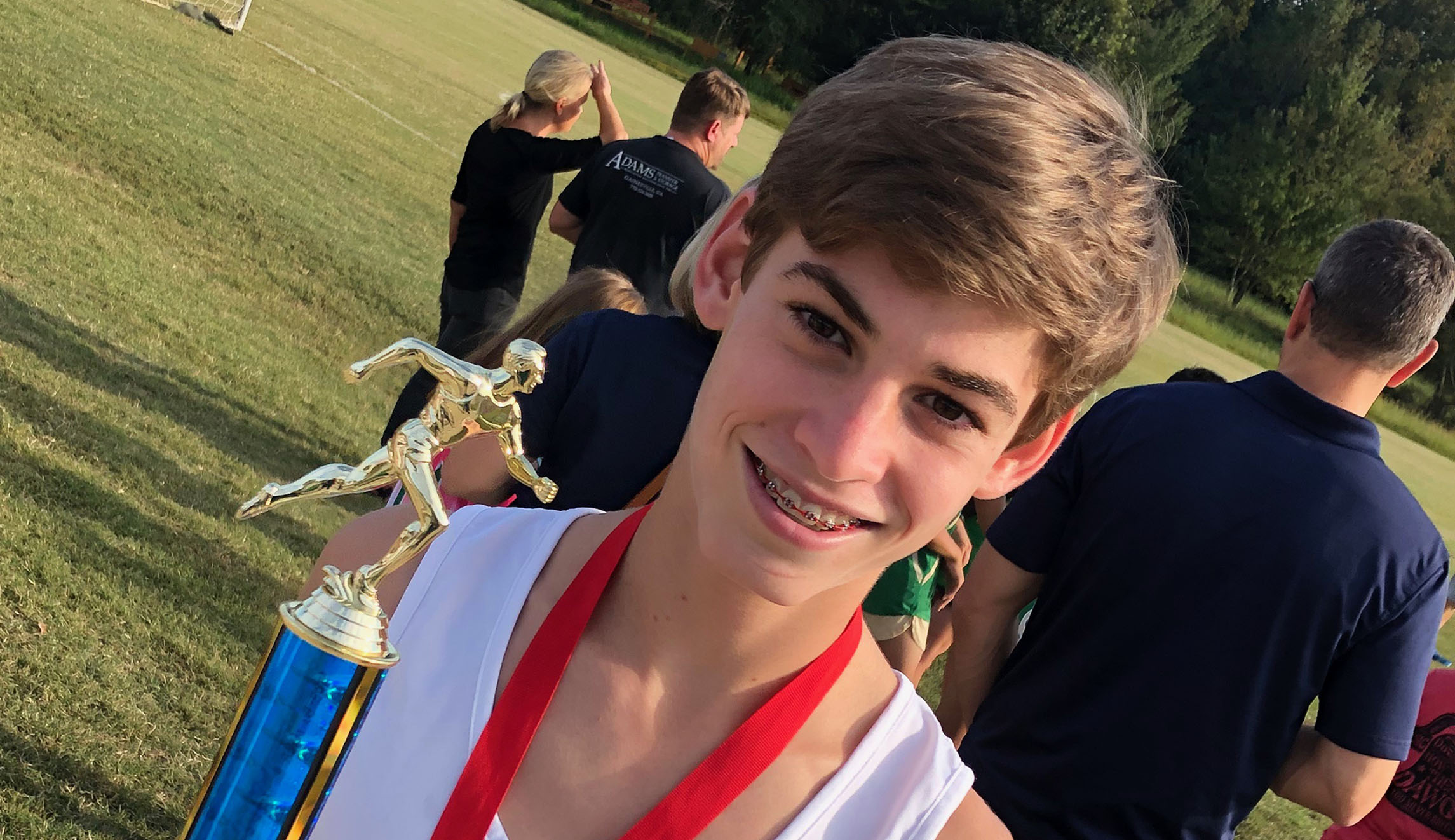

JD is “Mr. Super A+, does everything great, learns it all the first time … and didn’t miss a beat,” Susan said. “He has made tremendous academic progress, tremendous social progress, he has his first girlfriend, has learned two sports … he is thriving in every way because of face-to-face school.”

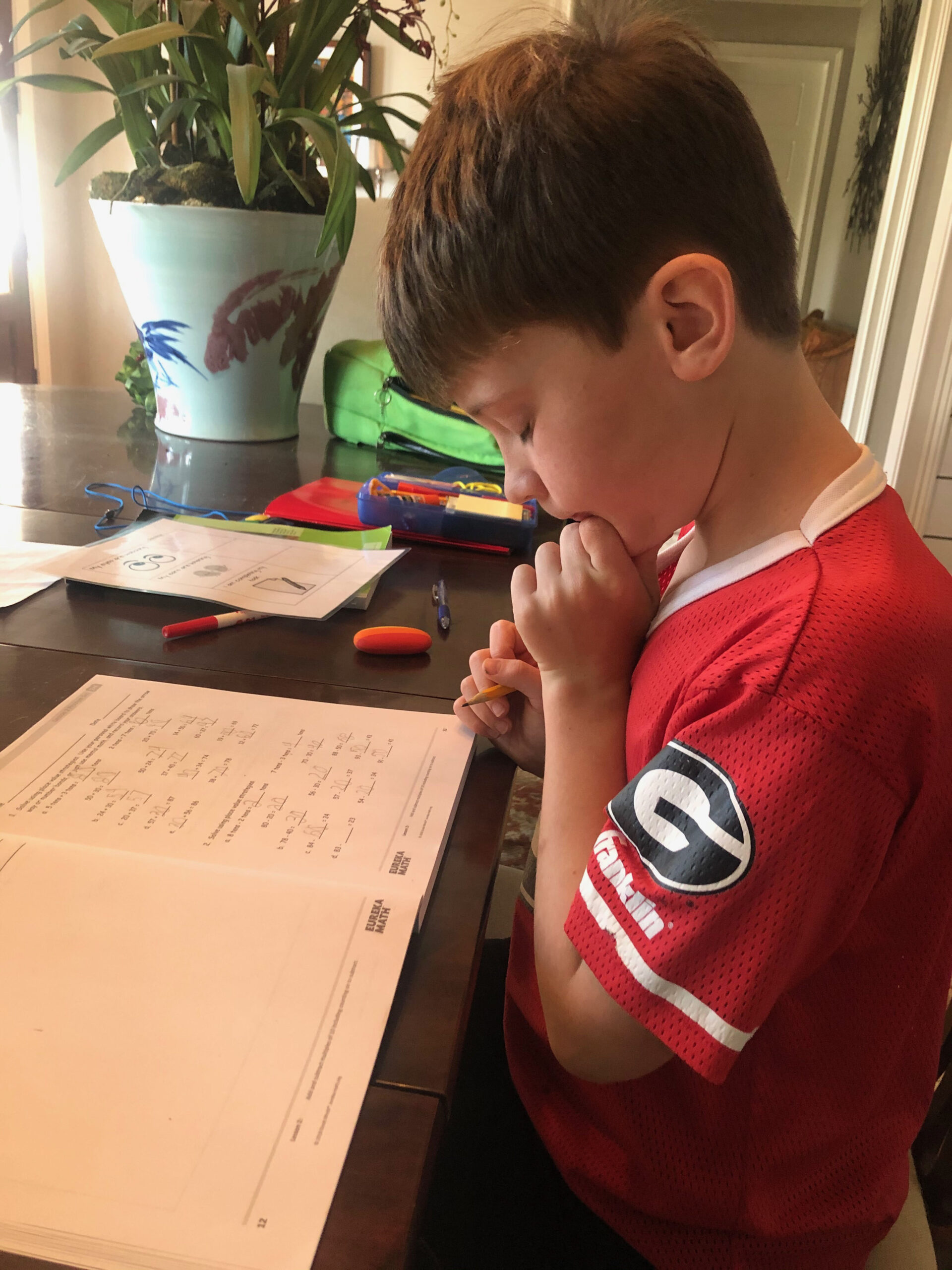

Ethan, who has dyslexia and a chromosomal issue that adds to a learning delay, has had a much harder time.

Almost all of his learning for the better part of a year has been virtual, a mix of synchronous and asynchronous learning that Susan described as “a nightmare” for me.

“It’s really hard to keep a second grader’s attention in a small breakout group on Zoom, especially when you hear all the other household background noise,” she said. “You hear parents yelling, you hear other students learning, you have technical difficulties, and second-graders can’t manage past all that and focus on the learning content. It doesn’t happen even with me sitting right next to him.”

STUDENTS LEFT BEHIND: THE EFFECTS OF SCHOOL CLOSURES ONE YEAR ON

Susan, a senior microbiologist at Johnson & Johnson who is earning her second master’s degree at Harvard, watched frustratedly as Ethan’s reading aptitude slipped over the year.

“I am doing all the things to help my little one read,” she said. “If they tell me to work on sight words, we work on sight words. Whatever they tell me, I do.”

When he was attending in-person class, Ethan had “phenomenal special education teachers” and was making progress. But in the year that he’s been learning remotely, his reading is back to a first-grade level, and he has had a hard time staying on track.

“I personally have had major stress,” Susan said. “I am very active in my career, and I literally would be side-by-side with my son on a Zoom meeting pretending everything’s good, listening to him stammer and sputter because he can’t pronounce anything he’s trying to read, and smiling, like, ‘Good job, honey!’, and on the inside, I’m, like, ‘I’ve got to call the psychiatrist, a counselor.'”

The struggles of remote learning in 2020 and 2021cast a critical light on education inequality, mental health, and academic performance. It has also provided an in-depth look at the ability of students, teachers, and their families to adapt to a new scholastic landscape.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp ordered all public schools to shut down temporarily on March 18, 2020. Most of the state’s 180 public school districts have returned to some form of face-to-face instruction, but there are still holdouts in some of the state’s largest districts.

JD’s school returned to in-person learning in August.

In Clarke County, where Ethan goes to school, it was clear to parents such as Susan that the pandemic was something the schools hadn’t been prepared to handle.

“My expectations for how it would roll out were what the private school achieved,” she said. “Immediately, they put a communication plan in place. They put a plan in place for contact tracing. We have an app [that we use to] check our kid in every day and records his symptoms. They’ve got virtual learning options that work and that are easy.”

Susan credits the private school plan working so well because all students and educators had timely access to critical information.

That wasn’t the case at in Clarke County, which had problems right out of the gate.

“The public school had so many things to clean up in order to make learning accessible to everyone equally,” Susan said.

CDC RECOMMENDS 3 FEET FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING, DOWN FROM 6, IN REVISED SCHOOL REOPENING GUIDELINES

Clarke County is about 119 square miles and has nearly 130,000 people. It’s the most densely populated county in Georgia outside of the five counties in metropolitan Atlanta.

Most people have access to reliable cell service and high-speed internet — but the question is whether they can afford it.

AT&T had agreed to provide free or discounted internet service to all students in the county that needed it — but there was a catch. Eligible households could not have an outstanding AT&T bill on the books. Several did and had no way to pay it.

That’s when the PTA stepped in and paid off the overdue bills.

But that was just the beginning.

There were major issues with software, systems crashing, children not being able to sit still during instruction, and other issues at home.

Another second-grader in Ethan’s special education reading group had such a chaotic environment around him that it was almost impossible for him to retain anything.

Susan offered to let him come to her house where he would have reliable internet, good lighting, and a quiet space to learn.

“He and at least two other siblings and a dad are at home, in a one-bedroom apartment, and they are all doing their thing,” she said. “The dad’s watching TV, the other kids are trying to learn, and this kid can barely speak. This is not working for them.”

It’s not really working out for Susan either, who has been eager to get Ethan back to in-person learning as soon as possible.

But there have been some obstacles.

“Our school system has attempted to go back, and what we found was that our bus drivers were getting huge exposure, and they were all calling out, and we ran out of buses, and it shut down the system,” she said. “Then, our teachers were getting the virus, and we didn’t have enough subs [substitute teachers].”

Growing frustrated, Susan said she’ll be taking part in a training program to be a substitute teacher this weekend.

“I don’t know how to teach at all, but if all the moms … if we take turns, it might work,” she said. “I could take a vacation day from work if I need to. If we all did it, it would help.”

While some believe an immediate fix for Susan would be to spend $20,350 to send Ethan to Athens Academy, she disagrees and says that the private school is “not the right fit for Ethan.”

As far as the COVID-19 fear factor goes, Susan told the Washington Examiner that she has no problem sending her youngest son back to school.

“I am a scientist, and I have a pretty good understanding about how the virus spreads, and I have a good understanding of the controls the school has put in place to stop the spread, so for children’s safety, I am very comfortable sending them back,” she said.