As soon as the 2018 election is over, political media will start to cover the 2020 election. If Democrats take the House (and possibly the Senate), pundits on the left will argue that the GOP’s losses foreshadow an inevitable doom for Trump’s re-election. And if Republicans do better than expected, possibly holding onto both chambers of Congress, pundits on the right (especially the Trump-ian right) will say that the president is invincible and will surely be re-elected.

I’ve read a lot of commentary and watched a solid amount of cable news, and I can basically guarantee that someone with a high position or a lot of credibility will end up making one of these arguments. It’s not a great argument

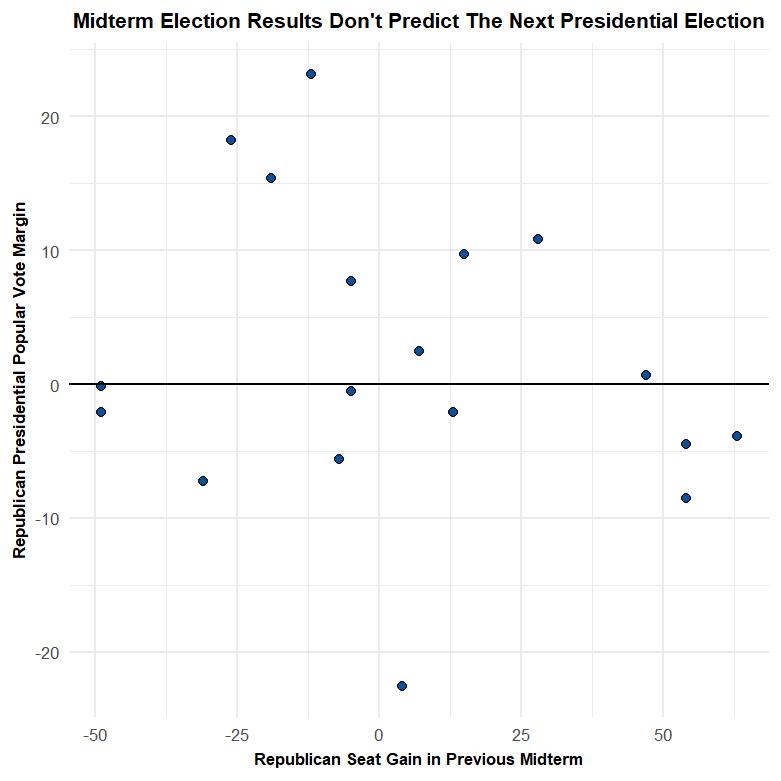

This scatter compares midterm election results to the results of the following presidential election. Each point is a midterm election (all midterms from 1946 to 2014 are included). The horizontal axis shows the number of seats Republicans lost or gained, and the vertical axis shows their popular vote margin in the presidential election held two years later.

There’s no pattern here.

Sometimes a terrible midterm is followed by a rough presidential election. In 2006, President George W. Bush’s Republicans lost the majority to Democrats (public opinion was turning against the Iraq war and the White House had struggled with its response to Hurricane Katrina), and two years later John McCain lost to then-Sen. Obama by a solid margin.

But that pattern doesn’t always hold. Republicans won a wave election in 1994, but Bill Clinton still prevailed in 1996. And House Republicans had a rough time in the 1982 midterm, but two years later Ronald Reagan won in a landslide.

And sometimes it’s just vague. In 1974, Republicans (led by Republican Gerald Ford) faced an enormous post-Watergate backlash. In 1976, Ford barely lost the Electoral College and lost the popular vote by only two points. Democrats could argue that 1974 predicted 1976 correctly – Democrats made huge gains in the House and went on to beat an incumbent Republican two years later. Republicans could argue that Ford managed to almost completely recover only a couple years after pardoning Richard Nixon, proving that incumbents will bounce back no matter what.

All of which is to say, an especially good Democratic year won’t tell us much about Trump’s chances of winning re-election in 2020.

And an especially good midterm election for the president’s party probably wouldn’t tell us much either.

In 2002, George W. Bush’s Republicans managed to gain seats (a rare occurrence for an incumbent party in a midterm election) and Bush went on to win the 2004 election by a decent margin. But George H.W. Bush didn’t have the same luck. He faced a relatively mild midterm in 1990 and went on to lose the 1992 election to Bill Clinton. Similarly, Bill Clinton’s Democrats had a relatively good 1998 midterm, and the 2000 election ended in a near-tie with George W. Bush winning the Electoral College despite Al Gore edging him out in the popular vote.

Put simply, I wouldn’t recommend using 2018 results to forecast the 2020 results. In my view, Trump’s odds of re-election (conditioned on him not being removed from office, passing away, etc.) are somewhere around 50-50. You could argue for shifting those odds up (e.g. Trump is an incumbent and he should get a bonus for that) or down (e.g. we’re due for another recession and he’s already unpopular), but most credible arguments along those lines don’t use 2018 results as a predictor of 2020.

Readers who buy my argument might still feel disappointed. Political junkies love trying to read the tea leaves on the next presidential election, even if that election is two, three, four or more years away. So I’ll talk through a couple things that I’ll be keeping my eye on in 2019 to get a sense of what might happen in the 2020 election.

First, I’d watch the 2020 Democratic primary, specifically the top contenders (whoever that may be) and how favorably voters rate them. Trump was the most disliked presidential candidate in the history of presidential polling, but he was able to win because he ran against Hillary Clinton, the second-most disliked presidential candidate in history. It’s possible that the toxicity of our politics will drive the Democratic nominee’s numbers down (no matter who it is). Or it’s possible that Trump and Clinton were aberrations, and that Trump would have a lot more trouble putting away a more likable opponent.

I’d also watch the gap between Trump’s economic numbers and his overall approval rating. As others have pointed out, Trump’s approval rating on the economy has consistently outpaced his overall approval rating. That asymmetry suggests that people are generally happy with the state of the country (the economy seems to be doing well and there are no unpopular wars dominating the headlines), but they don’t like Trump.

If Trump manages to keep his personal negatives in check (something he hasn’t been able to do), he might be able to shrink that gap and gain an advantage. Alternatively, if a recession (or just a rough slowdown) hits or if he bungles a major crisis, he won’t have much padding and his poll numbers could hit truly subterranean levels.

And, finally, there’s the Russia investigation, probably the least predictable but potentially most consequential element of the Trump story. I could sketch out numerous different possible scenarios for Trump and Mueller, but frankly I have no idea how to accurately assign probabilities to those scenarios. I’m not sure anyone does. But the Russia investigation has the potential to have huge effects on the Trump administration, so it’s worth keeping an eye on as 2020 gets closer.