At the final press briefing before this weekend’s White House Correspondents’ Dinner, reporters crowded around the 49 assigned seats in the Brady briefing room. Press secretary Sarah Sanders read a statement before taking questions for 18 minutes, calling on just 15 people.

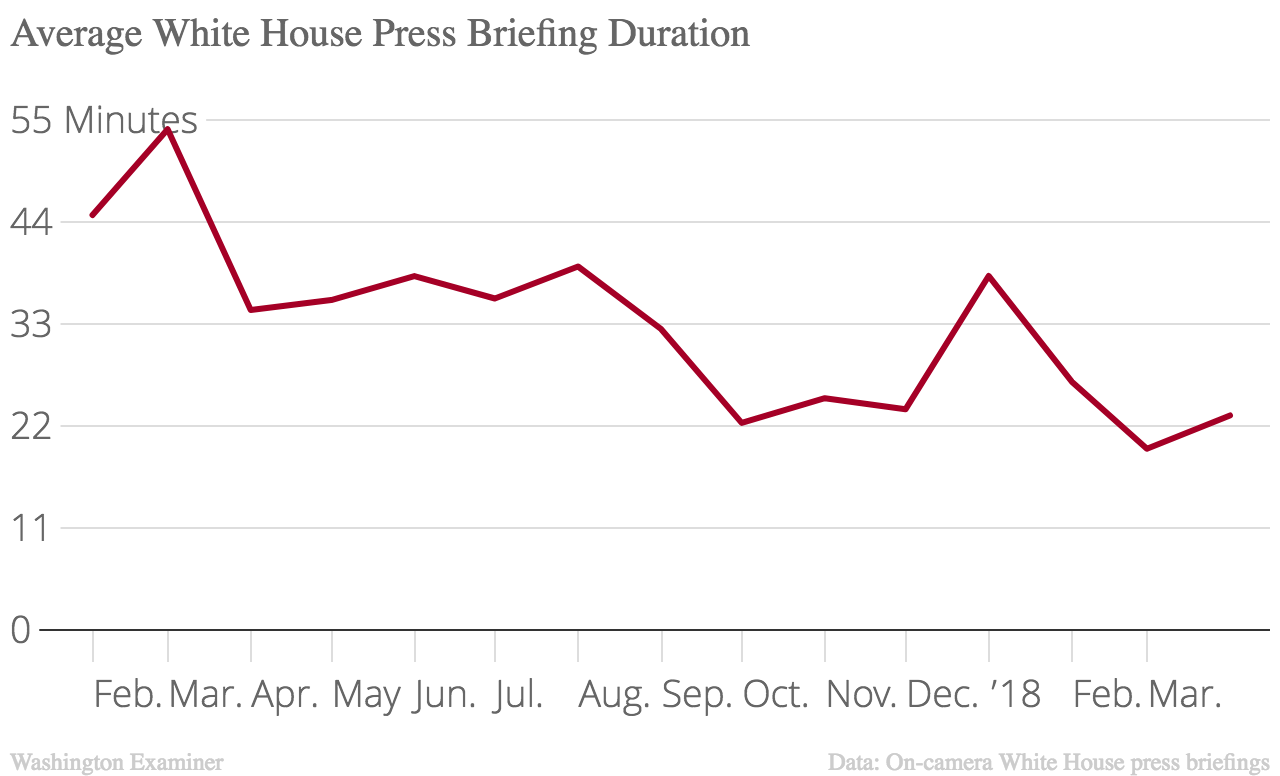

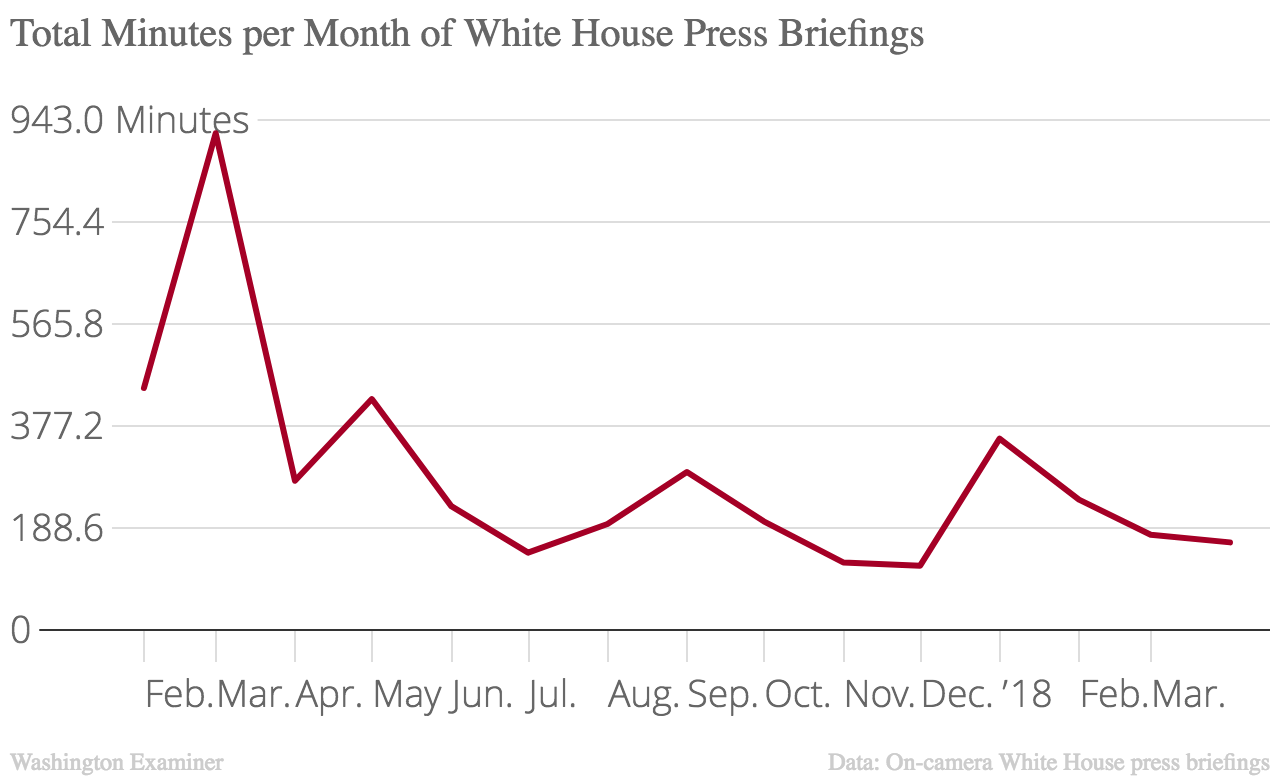

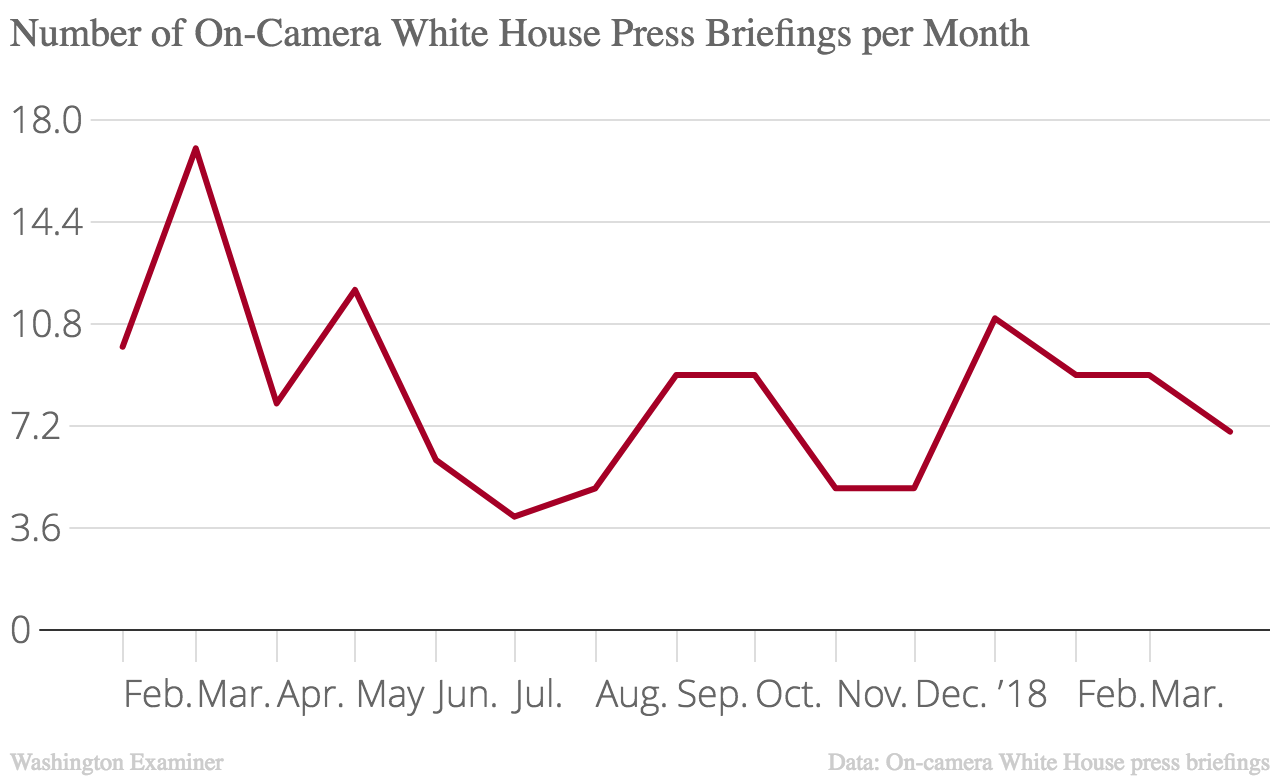

It was an increasingly familiar pace. Of the 17 briefings in March and April, just two lasted longer than 24 minutes, reflecting a pivot toward brevity since Sanders took over in late July.

It’s probably a necessary evolution, said Sean Spicer, who as Sanders’ predecessor routinely took questions for more than a half hour, calling on as many as 44 reporters at a briefing.

“The briefing is not serving a constructive purpose anymore,” Spicer told the Washington Examiner. “It doesn’t need to exist every day, and it definitely doesn’t have to be on camera.”

Spicer’s energetic briefings tested various changes, including adding Skype questions from local journalists and talk radio hosts. He sought out less-famous and niche journalists near the back of the briefing room. And toward the end of his tenure, he turned off the cameras.

“When they knew it wasn’t on camera, they wouldn’t come,” he said. “That really speaks to motive. The focus should be on providing information to the public.”

Spicer said his effort to diversify who got to ask questions was worthwhile, but failed to solve deeper issues, such as TV journalists repeating variations of the same question so each can have a clip of themselves asking about major stories, which he called “a waste of everybody’s time.”

“One of the lessons learned during my tenure was that more of these folks just wanted to get their YouTube clips or their segment on TV versus get information,” he said. “It wasn’t about forwarding a story; it was about their personal brand.”

Although Spicer argues for curtailing briefings in favor of more off-camera engagement, another former press secretary believes other methods are worth trying.

“The main thing would be to take it off camera, but that would be a shitstorm, I know,” said Mike McCurry, who worked as press secretary for President Bill Clinton from 1994 to 1998.

McCurry said another option would be to embargo video of briefings, to force outlets to “select the most newsworthy moments.”

“You’d still get some posturing for the camera, but restricting live coverage — unless there is, in fact, real breaking news — might help,” he said.

A more vexing issue, he said, is the fact that television reporters “all have to ask some version of the same question because their broadcasts want to use their correspondent and not a competitor’s.”

“Taking the briefing off camera might address that, but it would provoke further war between the White House and the press, which I generally think we need less of,” he said.

McCurry said it may be useful for the briefings to follow a format where journalists exhaust one topic at a time. He said this was done when he briefed reporters at the State Department in the early ‘90s and that questions “usually did not duplicate.”

Sanders did not respond to a request for comment. But brevity has its benefits.

“You want the policies to be the same at the end of the briefing as they were at the start of the briefing,” said Martha Kumar, director of the White House Transition Project.

Kumar, who attends briefings and keeps detailed records about who asks questions and how long each exchange lasts, said Sanders’ briefings are notably short, but that she generally calls on only slightly fewer reporters than Spicer, sometimes fitting several answers into a minute.

Snappy responses also reduce the potential for misspeaking, Kumar said, pointing to when Spicer said Adolf Hitler had not gassed his own citizens, unintentionally overlooking the Holocaust, for which he apologized.

Kumar said it’s clear that Sanders gained an understanding of briefing-room personalities during her time as Spicer’s deputy, allowing her to better control the flow of briefings. Spicer, by contrast, often called on reporters he did not know, saying “ma’am” or ”sir,” rather than names.

Kumar said one particularly useful approach taken by Spicer’s was bringing cabinet secretaries or other officials to take questions. Sanders continued the tradition — notably with an October appearance by chief of staff John Kelly and a 74-minute January briefing with Dr. Ronny Jackson on Trump’s health — but Kumar said there have been fewer recently.

“I think they’re trying to sharpen the message,” Kumar said.

Kumar said all recent press secretaries brought different styles to the job.

“[President Obama’s first press secretary] Robert Gibbs used to go down the front row and then go down the second row,” Kumar said, meaning the briefings were largely about “TV reporters getting good visuals [with] strong statements and pointed questions.”

“[Obama’s final press secretary] Josh Earnest was smart about not working his way down the first row [and would] move it around,” she said.

Although journalistic showboating irks many participants, Spicer said he’s not sure he would support half-measures floated by McCurry, saying that delaying the airing of briefings may result in context-free tweets and confusion, and that he feels uncomfortable with the idea of controlling questions, even with one-topic limits.

Spicer said he’s proud of going out of his way to call on publications that cater to particular ethnicities, trades, and ideologies. “It’s important that people who are sending a reporter there have an opportunity to talk about issues that matter to their constituency,” he said.

Although the reporters fortunate enough to ask a question generally ask at least two, McCurry said he doesn’t fault reporters for cramming what they can into short briefings. He said that there was a less-rushed approach during his time.

“Mine probably went on 45 minutes or so on average,” he said. “Helen Thomas would preside and look around to her colleagues, and if no one was agitating for a question, she’d nod and give me the ‘thank you,’ which meant the briefing was over. It was up to them, not me.”