Anniversaries

From the Life of Gesine Cresspahl

by Uwe Johnson

translated by Damion Searls

New York Review Books, 1668 pp. (two vols.), $39.95

When Uwe Johnson, aged only 49, died on February 23 or 24, 1984, in the upstairs bedroom of his house in windswept Sheerness, Isle of Sheppey, England, he was all alone. His body was found only weeks later. Johnson’s neighbors remembered a man who, though he would visit the local pub at the same hour every day, otherwise kept to himself. In his work, however, Johnson rubbed shoulders with a whole universe of people.

This is true especially of Anniversaries, one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, a massive achievement on the scale of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time or Joyce’s Ulysses that deserves to be better known. Full disclosure: I love this outsized, bulging, bursting-at-the seams colossus of a novel, a book to live by and with. It defies classification, the way its author did, too.

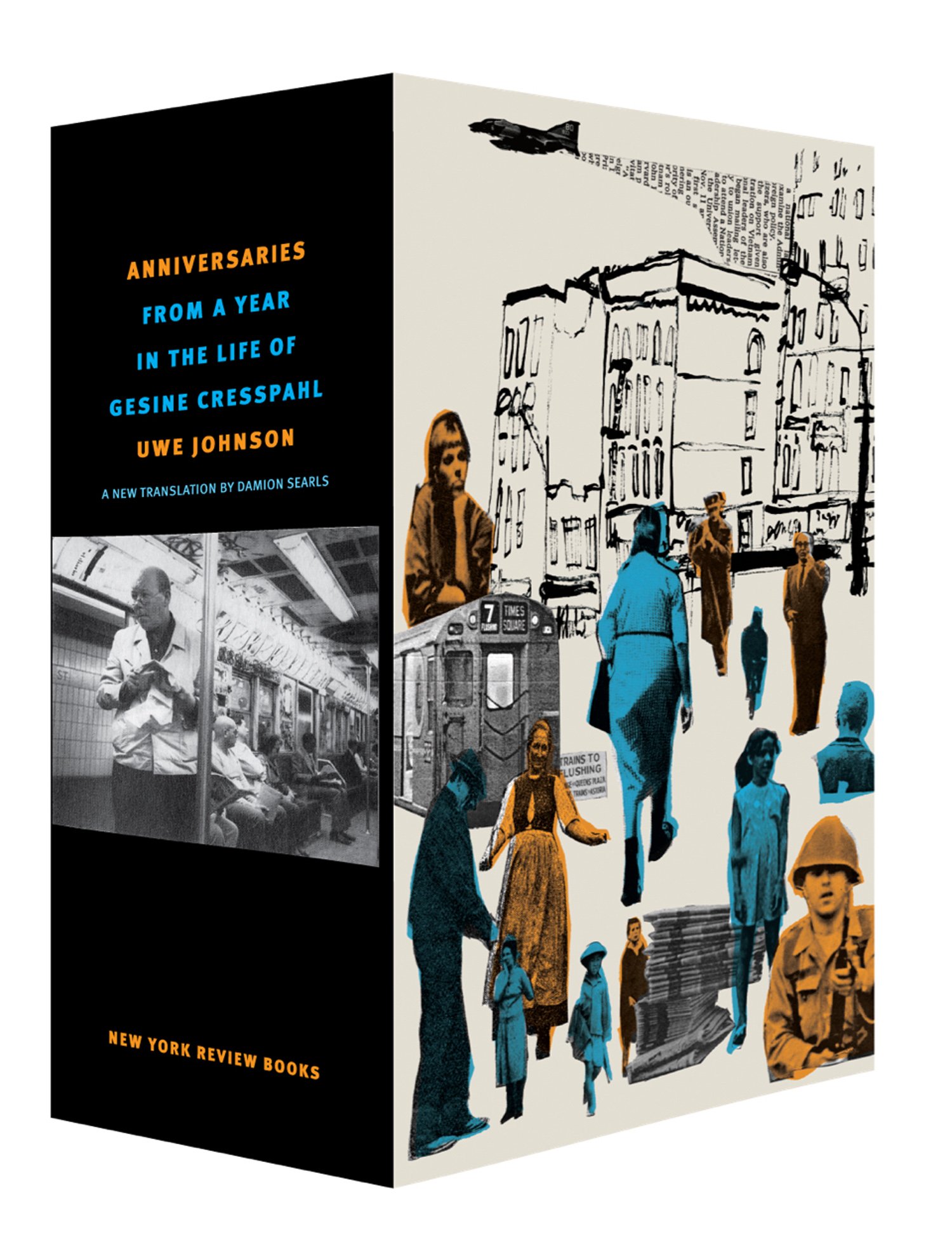

Born in what is now Poland, Uwe Johnson grew up in a small town in the East German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, left the GDR for West Berlin when his career as writer took off, and later moved to New York where he began writing Anniversaries. He finished the novel in Sheerness, where he spent the last decade of his life. Johnson’s masterwork, which runs to four volumes and close to 1,900 pages in the German original, was first translated into English by Leila Vennewitz in 1975 and 1987, but from a manuscript radically abridged by the author himself (the translation of volume four was completed by Walter Arndt). Now we finally have, in a beautifully printed slip-cased edition, the first complete English translation, the product of years of exacting work by Damion Searls—cause for celebration indeed.

The central character in Anniversaries is Gesine Cresspahl, a 35-year-old woman from the fictitious Mecklenburg town of Jerichow, who, as the novel opens, has been living and working in Manhattan for several years. As her 10-year-old daughter Marie slips further and further into modern American life, Gesine begins to hold conversations with people long dead, because she wants her daughter to understand “how I think it was.” From August 21, 1967, to August 20, 1968, day by day, Gesine records her reflections, interweaving current local and political events with stories from her and her family’s lives in provincial Germany. Interrupted by the precocious daughter’s prodding and distracted by unsettling news, taken from the New York Times, about the present state of the world (the Vietnam war, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, the Prague Spring), Gesine gathers around herself the vanished figures from her past: her grandparents and parents, neighbors, friends, and classmates. Marie’s father, Jakob, long dead, darts through those flashbacks the way Gesine’s current lover, D.E., also originally from Mecklenburg, appears in and disappears from her life today. Memory is a cat, she muses, independent, incorruptible, and irritatingly intractable, “and yet a pleasant and beneficent companion” if it wants to be.

The problem is that, more often than not, that cat doesn’t want to be pleasant. Violence invades Gesine’s memories at every turn, from her mother’s suicide after she had shown sympathy for a Jewish girl shot by the local Nazis to the drowned bodies of concentration camp victims washing up at the shore to her best friend’s rape at the hands of Russian soldiers. Anniversaries is one of the busiest and most disquieting novels you will read—so many names and lives, so many fears, mistakes, and regrets, so many shattered hopes. For all the noise these visitors from the past are still capable of making, the underlying challenge, issued by young Marie to her mother, remains: “You didn’t stop your war and now you want me to do it for you? When you were young they were preparing their war all around you and you didn’t notice anything!”

Yet there are few outright villains in the novel—the town’s Nazi mayor, perhaps, or Gesine’s uncle Robert, an early convert to National Socialism, said to be responsible for a massacre of Ukrainian children. Many characters are merely pathetic, like the local pastor who shouts “Heil Hitler” when entering a room where somebody has just died. Most are like the rest of us, flawed, easily discouraged, clinging to the shreds of our dignity, good-natured at heart but determined to survive at all costs when the odds are against us.

Johnson’s novel occupies the present as much as it does the past, capturing the way rain in New York changes to snow, thin, watery, barely sticking to the sidewalks; the stink of the crowded subways; the shouts of the children in Riverside Park; the daily sufferings of the city’s black citizens, whose lives Gesine will never fully understand. “You don’t know anything. You’re not black,” her building’s custodian tells her.

Searls’s nimble translation faithfully reflects the constantly shifting registers of the novel and bravely tackles a problem Vennewitz avoided: finding an English equivalent for the dialect spoken at crucial moments in the novel by Gesine herself and her ghostly visitors, a form of Low German known as “Platt.” For example, when Gesine visits her lover’s mother to tell her that D.E., her only son, has died in a plane crash, the conversation is rendered entirely in Platt. Their tense exchange is powerful precisely because the dialect makes the frightening fact of someone’s complete disappearance seem even more final. “Nu nicks mihr?” wonders D.E.’s mother, which Searls translates as “Now theres nothin?,” a solution that seems preferable to Walter Arndt’s unremarkable “now nothing left?” Granted, it’s impossible to translate dialect well. I well remember how, attracted by the shocking cover, I was reading a German translation of William Faulkner’s Sanctuary I had taken from my father’s library, I was disappointed when Popeye, one of Faulkner’s scariest characters, opened his mouth to speak with a lilting, folksy Berlin accent. Searls’s halfway solution—to render “Platt” as somewhat ungrammatical spoken English (“lettit go”; “a hunnerd an fifty”)—at least alerts the reader that something here is different.

In Johnson’s Anniversaries, history has no redemption to offer, no salve to heal our wounds. If authors of similar monumental works, such as Proust or, more recently, Karl Ove Knausgaard, hover godlike above their sprawling narratives, Johnson seems to leave no one in control of this universe of hurt. The English title, Anniversaries, though Johnson himself approved it, doesn’t reflect the full meaning of the German original, Jahrestage, which literally means “a year’s days” or “days of the year.”

Because that’s what life is: a succession of days on which great and small things, things awful and awesome, happen or don’t happen, just as they did or didn’t for so many years before, and as they will or won’t for so many to come. What matters is that Gesine and her daughter make it through their anniversaries intact. Johnson’s novel constitutes an outstanding act of empathy, a rare example of a male author feeling his way into and fully inhabiting a female character, writing a monumental book that is, first and foremost, a tribute to the extraordinary resilience of women.

More than halfway through the novel’s first volume, Uwe Johnson—or “Comrade Writer,” as Gesine airily calls him—briefly enters his own novel, ostensibly to take part in a panel organized in New York by the Jewish American Congress, as Johnson did in real life. The topic: the recent electoral gains of the West German neo-Nazis. Gesine, who attends the event, is not impressed with her author. When Johnson argues that Chancellor Kiesinger didn’t get elected because of his Nazi past but because “this side of things” has been forgotten, his audience turns against him. He should be ashamed of himself, he is told, and: “He’s one of them.” Sheepishly, “Comrade Writer” admits his remorse to Gesine, the character he has created, saying, “If only I’d asked your advice first.”

One might be inclined to shrug this off as a moment of postmodern cuteness—the author ceding control of his text, a move bound to delight tweedy theorists. But I would suggest that Johnson’s befuddlement was not just an act. “Who’s telling this story, Gesine?” he wonders. Gesine’s succinct answer, literally translated: “We both are. Can’t you hear that, Johnson.” Neither Vennewitz nor Searls get this last sentence quite right. “Surely that’s obvious, Johnson,” offers Vennewitz, who at least captures Gesine’s irritation, while Searls’s rendition—“You know that, Johnson”—sounds more like an unneeded reminder than a rebuff. The last time we see the author he is disappearing into the subway, hurrying to a place where he no longer needs to explain himself.

Over the 15 years it took Johnson to write Anniversaries, the novel embarked on a life of its own. It indeed became difficult to say who’d written what and who’d created whom. Within 10 months of delivering the final volume, Johnson died in his unlovely island exile. A note in his wallet asked that he be burned, without song, eulogy, sermon, or music. “Nu nicks mihr.” Nothing left. And yet, as this wonderful new translation reminds us, Johnson had left us everything, too.