The presidential race continues to be the main focus of most pundits, but next week the country will vote for the entire House of Representatives and a third of the U.S. Senate. What is the state of play in these races? Over the course of this week, I’m going to outline where things stand, starting first with the House of Representatives.

This is not a cycle where the Republicans should have expected to gain House seats. The GOP holds 246 seats, which is probably near the party’s ceiling, barring some kind of drastic realignment. That being said, the Democrats’ gains should not be all that great, all else being equal. It is exceedingly rare for an incumbent party to pick up a lot of House seats when it is trying to win its third straight presidential term. The last time that happened was in 1904, when Teddy Roosevelt won a landslide election.

But this year is unique because of Donald Trump. Long suspected of being a down-ballot drag on Republicans, he has made it hard to get a read on where exactly things stand. Now that we are just a week away, however, we can get a clearer picture than we could just a few weeks ago.

Put simply: It does not look like the Democrats have put enough seats in play to take control of the House, nor does the public mood seem to be leaning in that direction, either. To appreciate that, I will compare the late October state-of-play in the last five House elections to this year. This is especially useful because three of those elections (2006, 2008, and 2010) were “waves” in which one party won a substantial number of seats, while two (2004 and 2014) were not. So how do things look?

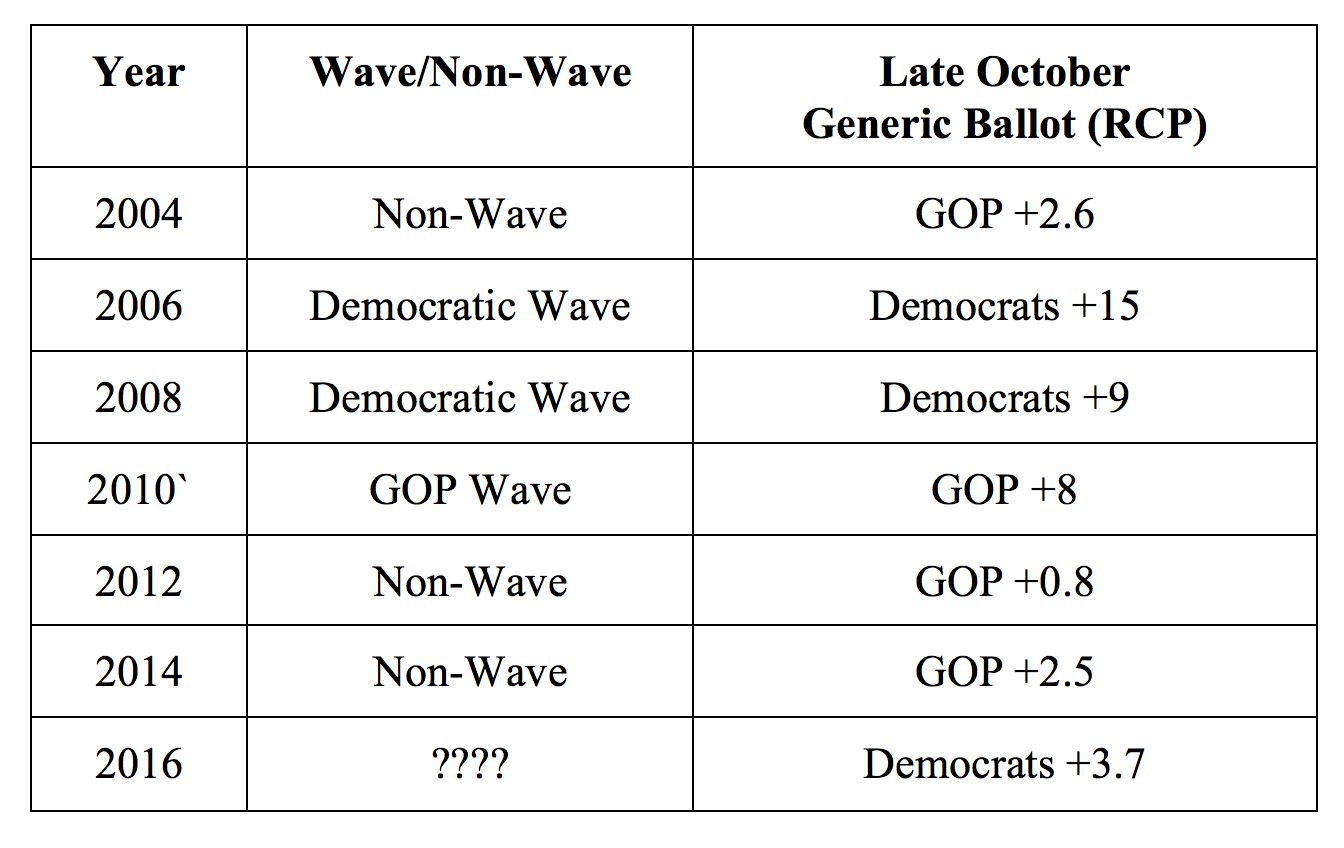

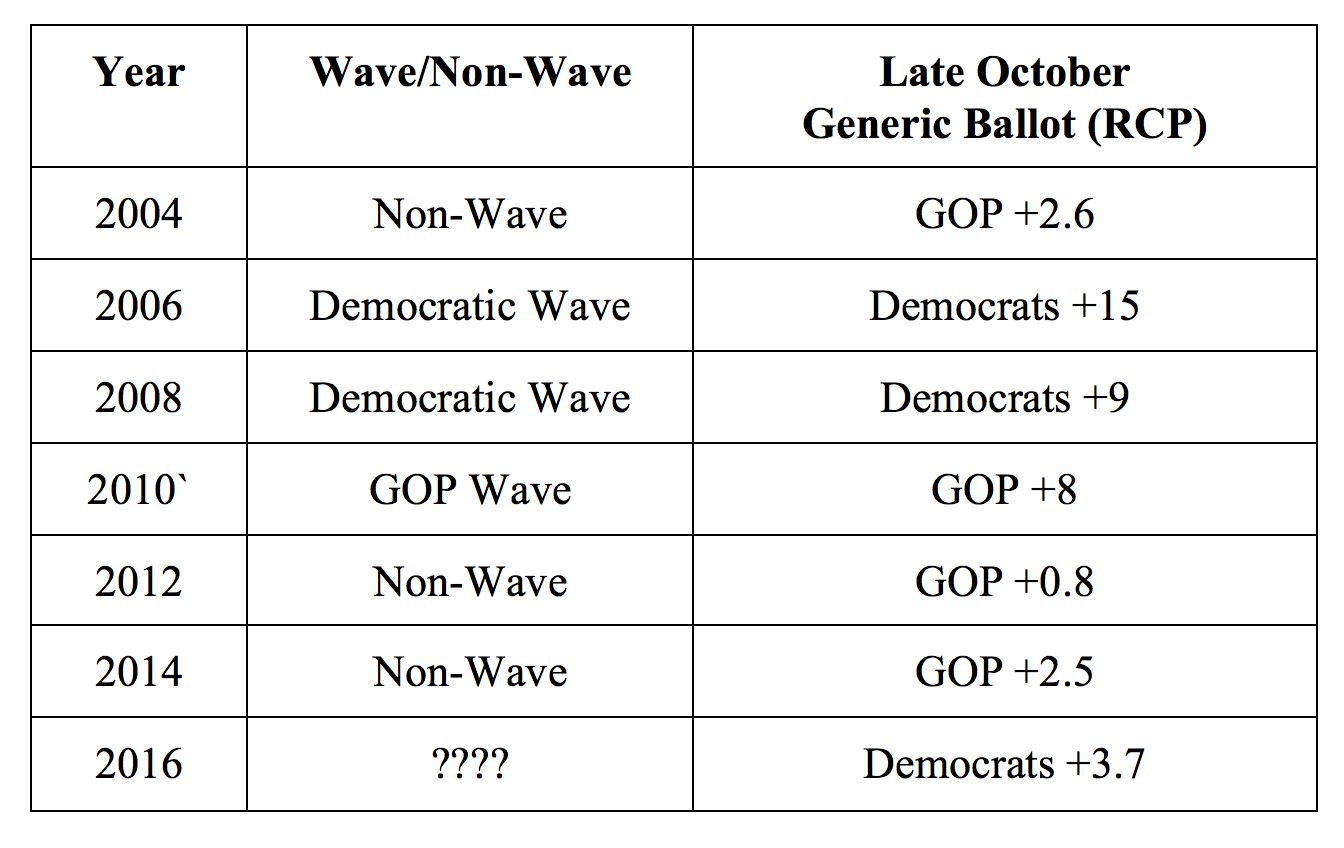

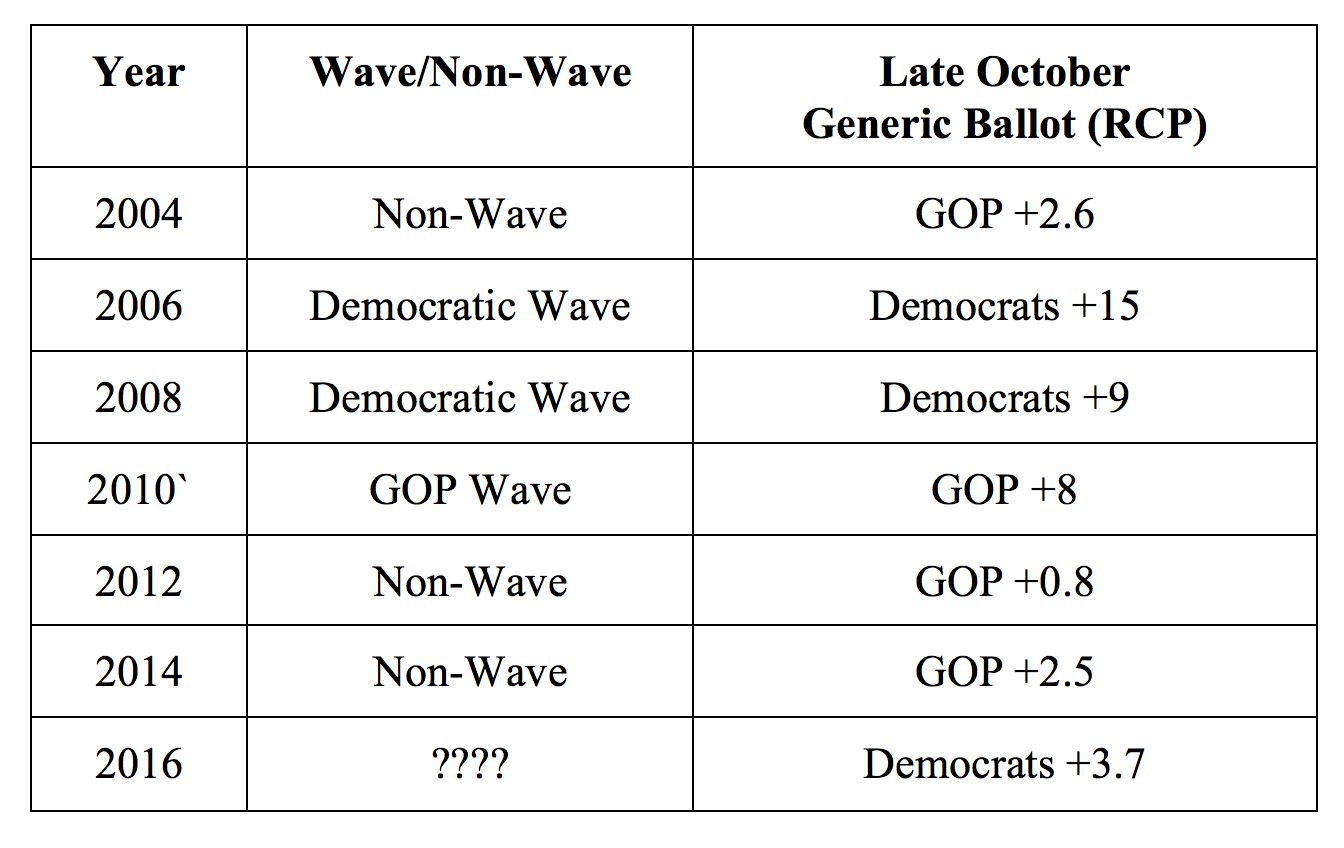

Let’s start with the generic congressional ballot. This is an imprecise indicator of congressional vote choice, because voters are not asked about the specific candidates in their districts, but rather about Republicans and Democrats in general. Still, it can be useful. Here is how it has stacked up over the last couple cycles.

The generic ballot number this cycle certainly points to Democratic gains, but it is about half of what we saw in the wave elections of 2008 and 2010, and roughly a fifth of the Democratic margin at this point in 2006.

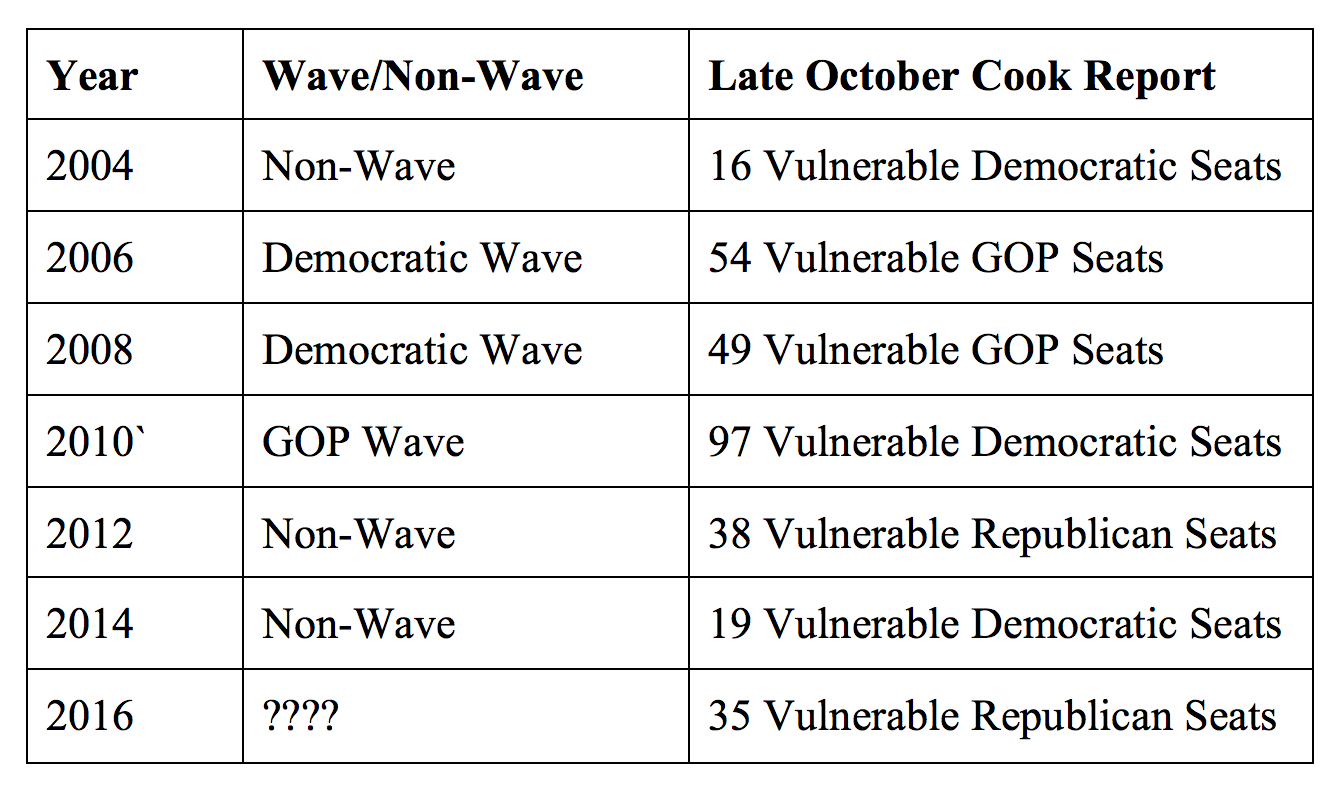

Again, the generic ballot is not a very precise indicator. It does not factor in conditions in the 435 individual districts. For that, we can turn to the Cook Political Report, a nonpartisan firm that has a great track at analyzing the House of Representatives. Cook breaks races down according to whether they are likely to be held by one party or another, they lean one way or another, or they are true tossups. Going back to 2004, we can see that this cycle has substantially fewer vulnerable GOP seats (rated as leaning Republican, tossups, or trending toward the Democrats) than has been the case in recent House waves.

Again, it looks as though the Republicans will lose seats this cycle—maybe a lot. But the Democrats have put fewer on the table this time around than has been the case in previous waves. Consider for instance the 2006 wave election, where the Democrats won 30 seats. That’s exactly the number they need to win to take control in 2016, yet as of late October the Democrats had only put two-thirds as many Republican seats in play.

As always, the usual caveats apply—especially this cycle. Trump is sui generis, and nobody really knows what is going to happen. But based on an analysis of the generic ballot and the state of play in actual districts, the Democrats have an uphill climb to take control of the House of Representatives.