A new analysis has rejected one of the popular criticisms of the 1996 welfare reform, namely that it led to an increase in deep poverty by preventing some single-mother households from receiving government help.

Instead, government data indicates that poverty fell overall, without any increase in deep poverty, when government benefits and tax credits are taken into account and inflation is properly accounted for, according to new research from the conservative Manhattan Institute.

Lawmakers “should reject the increasingly conventional view that extreme poverty has dramatically increased and the view that welfare reform did more harm than good,” concludes the report, published Monday to mark the 20th anniversary of President Bill Clinton signing the reform legislation.

Scott Winship, the report’s author, said in an interview with the Washington Examiner that he was motivated to study trends in deep poverty because he has been “appalled” by recent efforts to recast the 1996 reform, which instituted time limits and work requirements on cash welfare, as a disaster.

Much of the criticism of the law has been spurred by the publication of a new book, $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America, written by prominent Johns Hopkins sociologist Kathryn Edin, with Michigan professor Luke Shaefer. The book suggests millions of children live in families getting by on less than $2 a day and that the welfare reform law is to blame for forcing more people into such terrible situations.

Winship, however, finds in his study of the data that there were practically no children of single mothers in extreme poverty at the time welfare reform was signed in 1996, and that the same was true in 2012, the last year for which data was available.

The problem with the claim that extreme, $2-a-day poverty has risen, Winship claims, is that it fails to take into account the non-cash government benefits that have replaced cash welfare, it ignores the growth of low-income tax credits and it improperly accounts for inflation.

The data used in the claim that welfare reform boosted extreme poverty exclude government programs, such as food stamps and housing aid, that have grown in recent decades, as well as the earned income tax credit, which has been expanded several times.

Leaving those programs out of the analysis ignores that the U.S. has effectively decided to provide more benefits in-kind, rather than through cash, Winship argued. “To say this isn’t worth anything is to cast into doubt why we’re spending a trillion bucks” on means-tested benefits such as food stamps, he said.

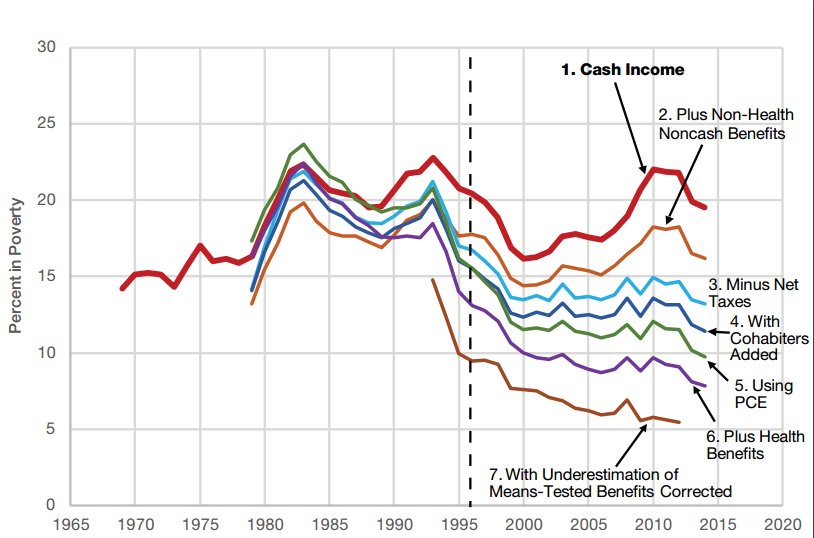

To include those benefits and make apples-to-apples comparisons with the past, Winship made a number of adjustments to the data that are more commonly reported. While each of those adjustments involve a judgment call, Winship said his intent was to create a measure that takes into account all the resources — including earnings, government benefits, tax breaks, etc. — that help families make the purchases they need.

This data represents the child poverty rate.

Among the bigger adjustments are the use of a different inflation gauge to measure the poverty line and count the income of cohabitating couples.

He justifies each of the choices he makes in the lengthy paper, which has five appendices and 230-plus footnotes.

The overall thesis is backed up with reference to easily understandable datapoints, such as the note that fewer children of single mothers are going hungry now than in the past.

Winship said he hopes his study provokes a response from Edin and Shaefer and liberal critics of welfare reform.

The 1996 welfare reform law has received new attention this year. In the Democratic primary, Sen. Bernie Sanders sought to discredit Hillary Clinton among liberals by tying her to her husband’s welfare reform law, which she has supported. Meanwhile, House Republicans have sought to advance the welfare reform agenda with a plan to expand work requirements.