A little more than a week before voters headed to the polls, entrepreneur and venture capitalist Peter Thiel said something Republicans will be debating for at least the next four years. “No matter what happens in this election,” the PayPal co-founder said, “what Trump represents is not crazy and it’s not going away.”

Thiel, 49, is but one example of what an unusual election this has been. The gay Silicon Valley mogul was roundly criticized for supporting Donald Trump for president and speaking on his behalf at the Republican National Convention. He did it again at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., telling his Beltway audience why they were wrong about the campaign.

“It was both insane and somehow inevitable that D.C. insiders expected this election to be a rerun between the two political dynasties who led us through the two most gigantic financial bubbles of our time,” Thiel said.

You might expect a high-profile supporter of the Republican candidate for president to offer such a negative appraisal of Bill Clinton’s 1990s economic stewardship, especially since his wife Hillary is the Democratic nominee. But to launch a similar attack on George W. Bush, the last GOP president, while not mentioning Barack Obama even once?

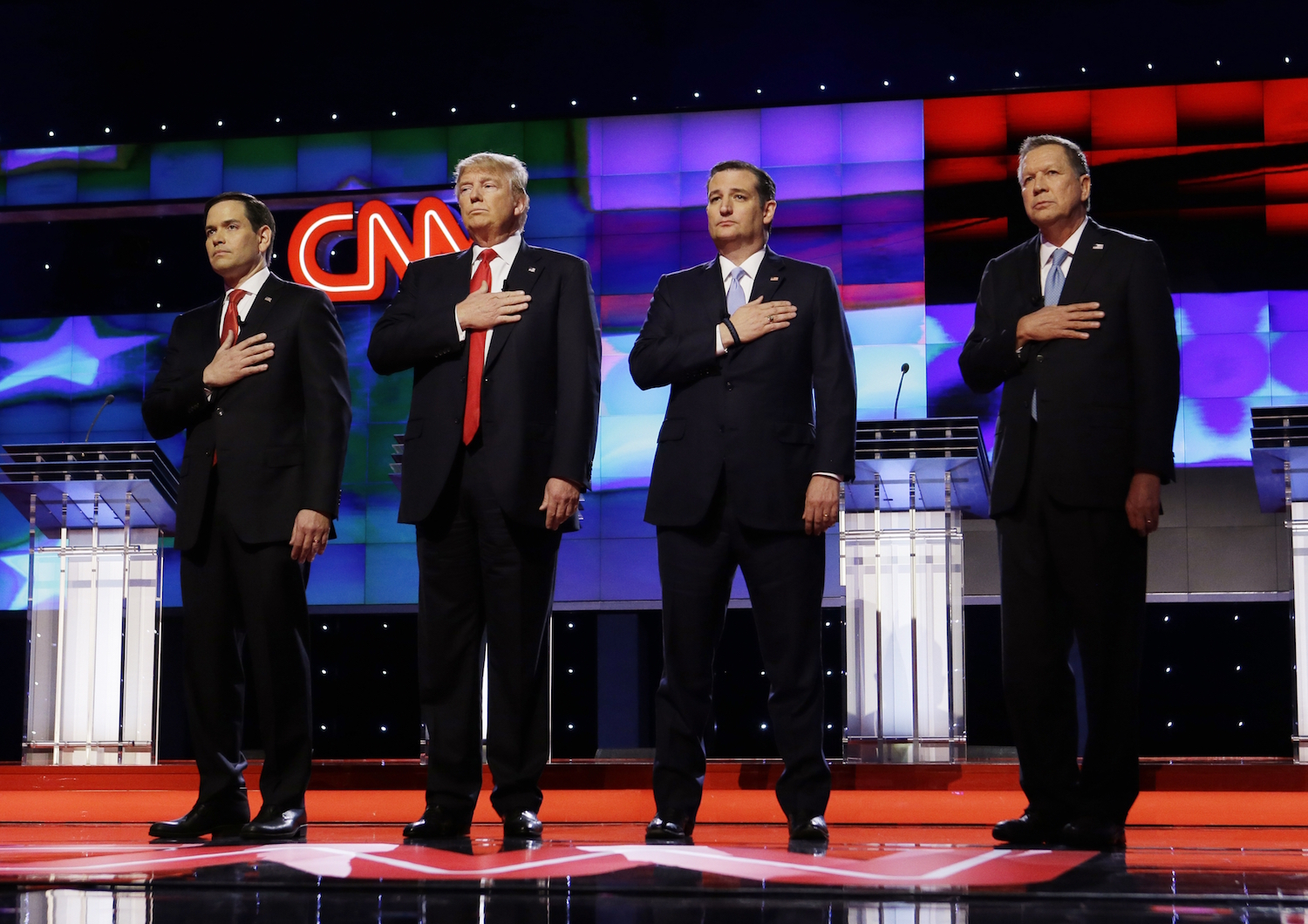

As polarizing as the 2016 election was for the country as a whole — some pollsters asked respondents if they would rather see the Earth destroyed by a meteor than vote for either candidate, and a surprisingly high percentage chose this option — it has been an especially painful and divisive experience for the Republican Party.

“I don’t know if I can ever go home again,” said a political operative who has worked to elect Republican candidates as the campaign came to a close. She isn’t alone.

Bob Dole was the only living past presidential nominee to attend the Republican convention. The only other to support Trump, Arizona Sen. John McCain, wound up rescinding his endorsement. The runner-up from the primaries, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, pointedly withheld his backing during a prime-time convention speech and held out until September. The two living Republican presidents didn’t endorse him at all.

As polarizing as the 2016 election was for the country as a whole, it has been an especially painful and divisive experience for the Republican Party. (AP Photo)

There was no love lost between Trump’s supporters and his detractors within the party. Amanda Carpenter, a former aide to Cruz and South Carolina Republican Sen. Jim DeMint, penned a widely discussed piece in the Washington Post accusing party leaders of failing to “defend women from this raging sexist, especially after so many Republican women, for so many years, eagerly defended the party from charges of sexism.

“If the next GOP autopsy has any credibility, it needs to contain political obituaries for Trump’s most ardent defenders,” whom she proceeded to list.

Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., suggested some of Trump’s supporters should be purged from the party just as the John Birch Society was excommunicated from the early conservative movement. “Those who want a Muslim ban, those who will disparage individuals or groups — yes, we ought to, we need to,” he told the New York Times not long after Trump clinched the nomination

“Nov. 9, I have a lot to say about all of you,” Fox News’ Sean Hannity warned anti-Trump Republicans on his radio show nearly two weeks before the election. After Clinton and Trump sparred on abortion during a presidential debate, commentator Laura Ingraham said, “That’s what Never Trump stands for, I guess. Roe v. Wade and partial-birth abortion. Fantastic.”

Trump is no ordinary Republican. His affiliation with the party has been intermittent. He has donated liberally to Democrats, including Clinton and incoming Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer. He explicitly ran against the Bush family. His entire campaign strategy repudiated the autopsy report on the 2012 election commissioned by the Republican National Committee. Still, he defeated 16 other candidates to become the nominee.

Whether a Trump venture succeeds or fails, all his projects become associated with his brand. What would it look like if his hostile takeover of the GOP continues past November? “Five, 10 years from now, different party,” Trump told Bloomberg Businessweek during the primaries. “You’re going to have a worker’s party. A party of people that haven’t had a real wage increase in years, that are angry.”

Entitlement reform, once considered the third rail of American politics, had been gaining momentum among Republicans nationally. George W. Bush proposed personal accounts for Social Security. House Speaker Paul Ryan’s budget blueprint, which has passed the lower chamber of Congress and earned the votes of most GOP senators, contains sweeping changes to Medicare.

Like many products bearing the Trump insignia, however, some of these innovations to the GOP platform were in fact manufactured elsewhere. (AP Photo)

Trump would reverse all that. “We will not cut Medicare or Social Security benefits, but protect them both,” he has said. He argues that economic growth alone can fix both programs, whose shortfalls are the biggest drivers of long-term debt. He has suggested Ryan’s approach is a political mistake.

The New York businessman also swears off the party’s commitment to free trade. On the subject of trade, he doesn’t quote free-market economists. Instead he invokes socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders, Clinton’s opponent for the Democratic presidential nomination. “We have one issue that’s very similar, and that’s trade,” Trump said of Sanders.

Like many products bearing the Trump insignia, however, some of these innovations to the GOP platform were in fact manufactured elsewhere. Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., previously argued the party should move in a more populist direction. The two main policy shifts he advocated were the rejection of certain trade deals and curbing unskilled immigration.

“What we need now is immigration moderation: slowing the pace of new arrivals so that wages can rise, welfare rolls can shrink and the forces of assimilation can knit us all more closely together,” Sessions wrote two months before Trump declared his candidacy (emphasis in the original).

Not everyone in the party likes these ideas — “protectionist nonsense” is how one Republican congressional aide described them — but Cruz, Scott Walker, Rick Santorum and Mike Huckabee all flirted with them in the primaries, too.

Trump’s formal immigration plan largely echoes Sessions’ proposals. Not surprisingly, Sessions was one of Trump’s first big endorsements. Stephen Miller, a senior Sessions aide who was highly involved in the immigration issue, moved over to the Trump campaign.

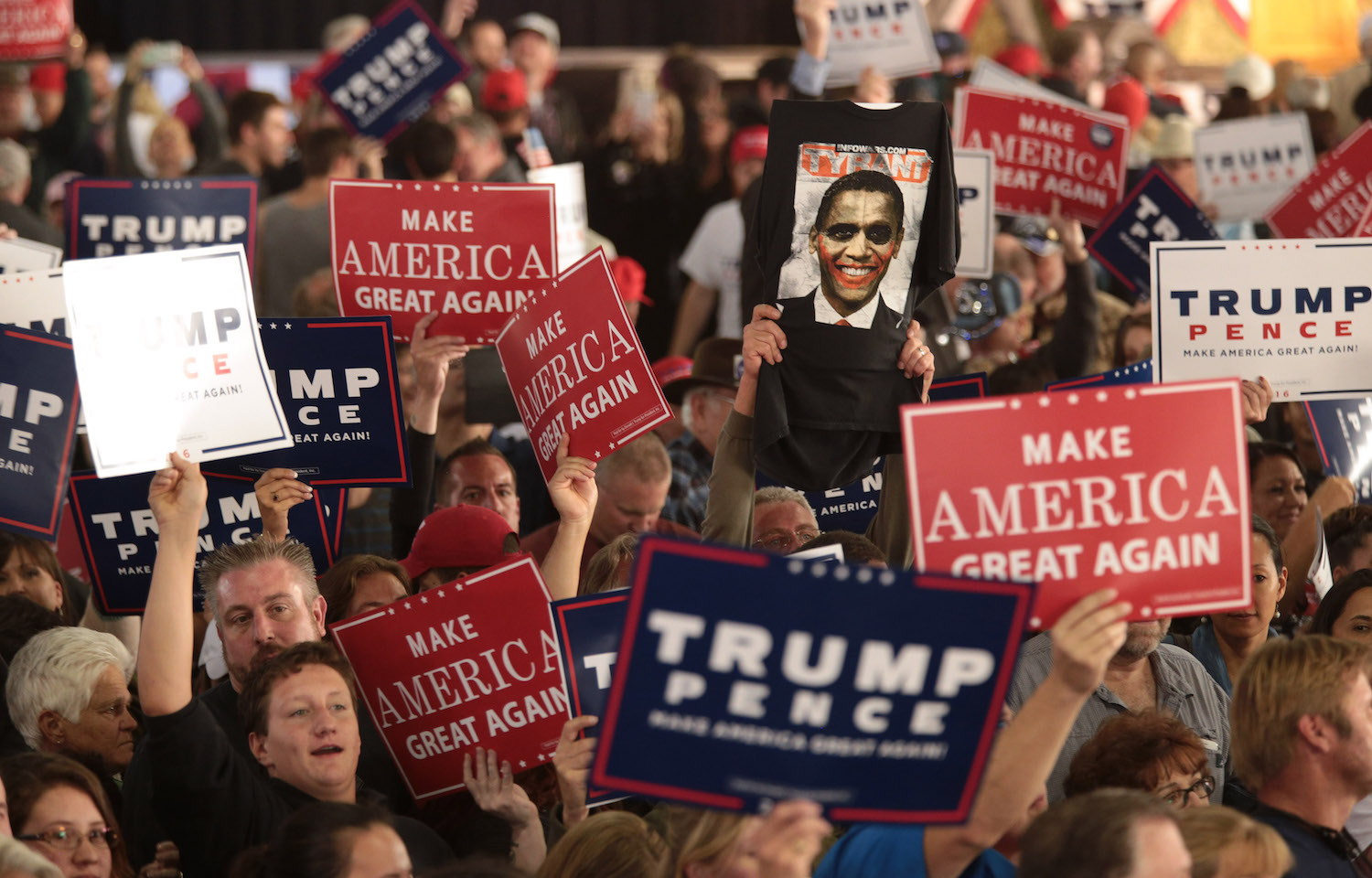

Beyond policy, a party takes on the characteristics of its presidential nominee in the same way a dog is said to look like its owner. A Trump GOP would move away from the sunny optimism of Ronald Reagan. (AP Photo)

Before Stephen Bannon was working for Trump’s presidential bid, he was publishing articles advocating a more populist and nationalist take on conservatism on his news and commentary site Breitbart.

While the soft-spoken Sessions has used Trump as a vehicle for advancing his own immigration-policy views within the party, there are some differences. Trump consistently brings up the wall and border security, but is not as outspoken about H-1B visas or legal immigration’s impact on American wages.

Sessions has tried to lower the temperature on immigration control by emphasizing the benefits for workers of all ethnicities and backgrounds. Trump does sometimes too, but it has been overshadowed by “Mexican rapists” and other comments widely perceived as anti-Hispanic.

On foreign affairs, Trump said he would look out for “America first,” a phrase that to some conservatives harkens images of isolationism prior to World War II. He has called the Iraq War a “disaster,” challenged the idea that George W. Bush actually kept the country safe since the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred on the Republican president’s watch and argued that wealthy allies in NATO and elsewhere ought to pay their fair share of defense costs.

Beyond policy, a party takes on the characteristics of its presidential nominee in the same way a dog is said to look like its owner. A Trump GOP would move away from the sunny optimism of Ronald Reagan. Even Reagan was no stranger to apocalyptic rhetoric concerning the growth of the federal government at home and Soviet influence abroad. “If we lose freedom here, there is no place on Earth to escape to,” he warned as early as 1964.

Nevertheless, Clinton and her surrogates frequently used the iconic 40th president against Trump. One 30-second ad commissioned by Priorities USA, the biggest pro-Clinton super PAC, juxtaposed Reagan describing America as one nation indivisible with Trump saying he’d like to punch someone in the face over a clip of one of his supporters doing just that at one of the candidate’s rallies. Clinton herself made frequent reference to Trump’s 1987 newspaper ad critical of Reagan.

Some of Trump’s supporters acknowledge there are differences, too. “He doesn’t think the force of optimism alone can change reality without hard work,” Thiel said, an implicit Reagan rebuke. Then the businessman was more direct. “He points toward a new Republican Party beyond the dogmas of Reaganism,” he declared.

The number of conservative print journalists and Republican political consultants willing to defend Trump was so small that some networks, most notably CNN, had to go out and recruit a whole new set of pro-Trump pundits to do the job instead. (AP Photo)

Ann Coulter, the syndicated conservative columnist and author of In Trump We Trust, argued that just as Reagan had to fight members of his own party on issues such as supply-side economics, abortion and foreign policy, Trump must do battle on a whole new set of issues.

“Today, the fight in the Republican Party isn’t over abortion, guns or the Sandinistas; the dividing line is immigration,” Coulter wrote. “Will we continue to be the United States, or will we become another failed Latin American state?

“On this,” she concluded, “it’s Donald Trump (and the people) vs. everyone else.”

No less a Reaganite than former United Nations ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick published an essay at the end of the Cold War which, with the fight against communism won, called on the United States to become “a normal country in a normal time.”

“There is no mystical American ‘mission,’ or purpose to be ‘found’ independently of the U.S. Constitution … There is no inherent or historical ‘imperative’ for the U.S. government to seek to achieve any other goal — however great — except as it is mandated by the Constitution or adopted by the people through elected officials,” she wrote.

Many Trump supporters have adopted a variation of this theme in defending his America first foreign policy. “Just as much as it is about making America great, Trump’s agenda is about making America a normal country,” Thiel declared. “A normal country does not have a half trillion dollar trade deficit. A normal country does not fight five simultaneous undeclared wars.”

Is this a new party Republicans want? Being post-Bush is one thing. It’s a safe bet that if Trump had openly run as a post-Reagan candidate in the primaries, he would have felt some pushback. Yet one Republican elected official in the swing state of Ohio compared it to his parents’ reaction to the collapse of the New Deal coalition, saying Reagan-style conservatism “had a pretty good run” but maybe politics was changing once again.

Even if Trump doesn’t have the same ideological influence on Republicans as Goldwater, he could have a similarly long-lasting effect on certain voting blocs. (AP Photo)

Grover Norquist downplayed the differences, saying Trump was Reaganite enough on taxes and regulation even if he cluttered this message with “misdirection” and “misdiagnosis” on trade and immigration. “That guy from El Salvador over there didn’t create the EPA,” he said.

Norquist argued that Washington’s problems were less due to management than government “trying to do things it can’t possibly do” competently. Corruption is inevitable with big government, he said, thanks to the amount of money flowing through it.

For many other Republicans, however, it is a bridge too far. Trump’s candidacy has opened huge fissures in the party and conservative movement. Established conservative magazines such as the Weekly Standard (which shares common ownership with the Washington Examiner) and National Review were passionately anti-Trump.

Cable news shows largely fill the right side of their guest lists with conservative print journalists and Republican political consultants. The supply willing to defend Trump was so small that some networks, most notably CNN, had to go out and recruit a whole new set of pro-Trump pundits to do the job instead.

Similarly, websites such as Breitbart and Laura Ingraham’s LifeZette frequently had to make the case for the Republican nominee alone without the support of other conservative media.

Talk radio remained a bastion of conservative Trump support. Proponents argued that this demonstrated where grassroots sentiment really was, saying hosts must win their own audiences rather than rely on a newspaper, magazine or website to provide one. Trump’s detractors countered that these hosts were providing entertainment, not journalism, and that their perpetual stoking of outrage had begun to threaten rather than advance conservative causes.

Even on talk radio, there were significant exceptions. Nationally, Glenn Beck emerged as a passionate anti-Trump voice. At the state level, Steve Deace aligned with the “Never Trump” crew in Iowa and Charlie Sykes did the same in Wisconsin. Perhaps relatedly, Trump lost both states to Cruz.

Ryan has been running a parallel campaign with Trump, resisting the businessman’s rebranding of the party at the same time he reluctantly supported him for president. (AP Photo)

Trumpism has no entrenched institutions or proven faction in Congress. As the Heritage Foundation’s Lee Edwards noted, the conservative movement was already well established by the time Barry Goldwater went down to defeat in 1964. Reagan was elected governor of California two years later. Trump imitators have yet to replicate his success in Republican primaries, meaning he could be a famous anomaly from which the party can easily move on.

Ryan, who beat one of those imitators in his own congressional primary by more than 80 points, has been running a parallel campaign with Trump, resisting the businessman’s rebranding of the party at the same time he reluctantly supported him for president. “In times as uncertain as these, it is easy to resort to division,” he said at his post-primary press conference. “That stuff sells, but it doesn’t stick. It doesn’t last. Most of all, it doesn’t work.”

Ryan has nevertheless found himself taking shrapnel from all sides. Anti-Trump conservatives are angry he endorsed the nominee, listing him among Republican “enablers.” Trump supporters have relentlessly attacked him as a “globalist” and “corporatist,” in some cases suggesting he secretly supported the independent conservative candidacy of Evan McMullin.

The Republican Party could seek leadership from figures who straddle between the pro-Trump faction and other conservatives, such as Cruz or Mike Pence. Or Republicans could turn to other leaders who were consistently anti-Trump, such as Flake or Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse.

But the divisions over Trump are much bigger than one man. How do Republicans cope with demographic change? Will the GOP remain even rhetorically a party of free markets and limited government? Or are those ideals too abstract and divorced from the material interests of actual Republican voters?

The Republican Party clearly has a problem with younger and nonwhite voters. It now has an enthusiasm problem even among millennials — a generation GOP pollster Frank Luntz has said may be “lost” — and minorities who identify as Republican. Trump may therefore exacerbate what South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham has described as the GOP’s “demographic death spiral.”

Even if Trump doesn’t have the same ideological influence on Republicans as Goldwater, he could have a similarly long-lasting effect on certain voting blocs.

Richard Nixon won 32 percent of the black vote against John F. Kennedy in 1960. Four years later, Goldwater — nominated in the aftermath of his vote against the Civil Rights Act — received just 6 percent. The party never recovered those voters. Could Trump similarly alienate a generation of Hispanics as their population share continues to grow?

Or would a “workers’ party” conscious of globalization’s costs as well as benefits ultimately deliver real economic gains to blacks, Hispanics and Asians as well as the white working class, reaching a more diverse electorate over the long term than movement conservatism has ever managed? “What do you have to lose?” Trump asks.

Regardless of whether Trump goes away, these questions won’t.