Josh Giegel wants to change the way people travel in the United States.

“How is it we have seen so much advancement in the computers we hold in our pockets, in our ability to launch missions to space, and to teach machines to think, but have yet to see a major revolution in transportation technology here on Earth that is faster, safer, cheaper, and greener?” Giegel, the CTO and co-founder of Virgin Hyperloop, asked during an interview with the Washington Examiner.

“I hope that my son thinks about cars and traffic the way we think about fax machines and the VCR,” he said. “Something we know a little about but has been completely surpassed by today’s technology. And along with it, a whole other world emerges.”

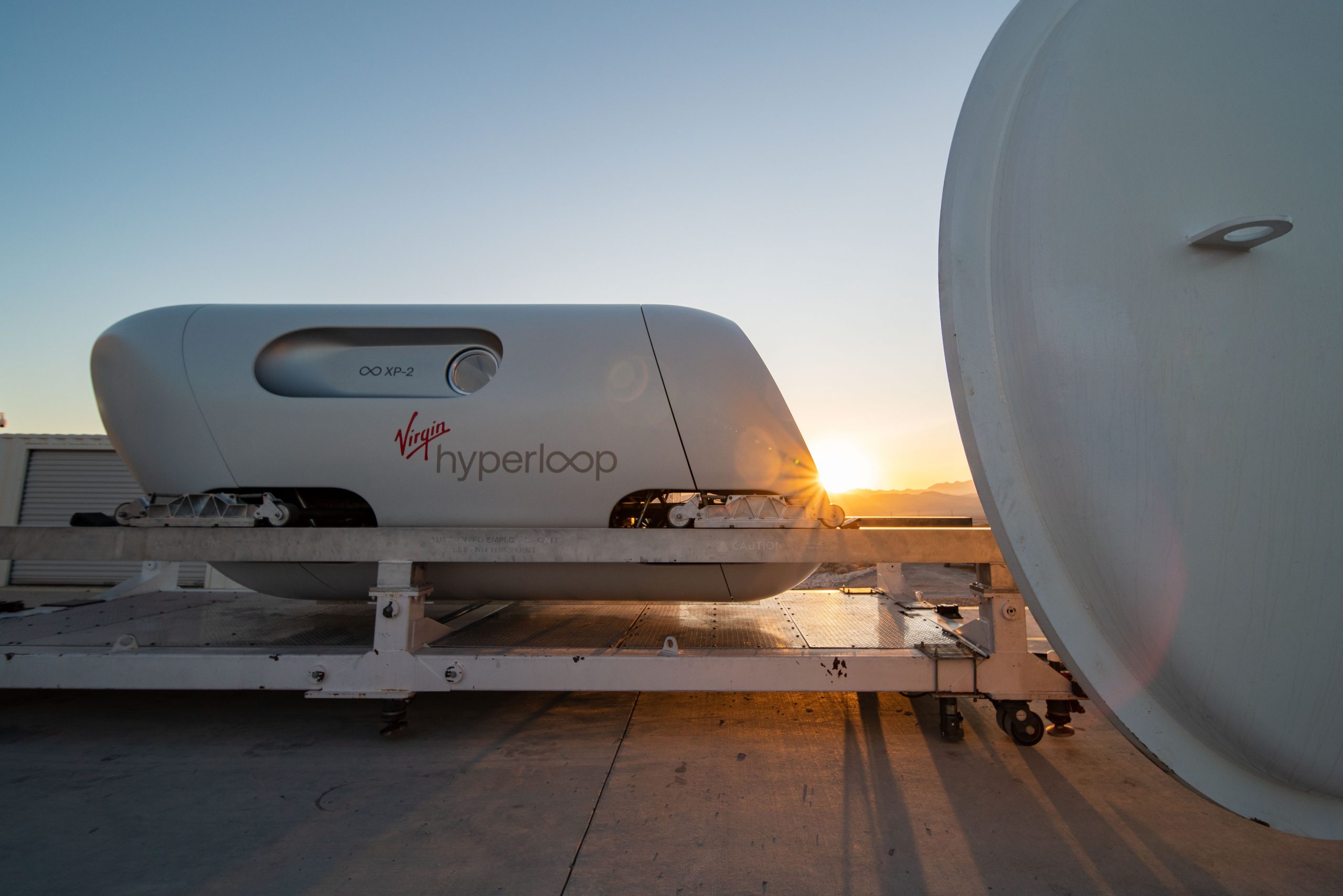

Last month, Virgin Hyperloop, one of the leading developers in the U.S. of a next-generation mass transit system, made history by successfully completing the first manned test ride of a hyperloop system, and Giegel was one of the world’s first passengers, alongside Virgin Hyperloop’s Director of Passenger Experience Sara Luchian.

The Hyperloop is a new form of transportation similar to the high-speed maglev trains in Japan, South Korea, and China, but has one key difference — the trains travel in a near-complete vacuum tube. In theory, a hyperloop train could travel at approximately 600 mph. At that speed, a trip from New York City to Los Angeles would take just a few hours.

The test ride was considered an “important milestone” and “a step forward in the promise” of ultrafast transportation. But even those who commented on the significance of the test questioned whether there was a place for hyperloops in transportation infrastructure in the U.S.

“For all the excitement, hyperloops remain an unproven technology that attempts to modernize the idea of marrying trains to pneumatic tubes,” CNN’s Matt McFarland wrote, “and that idea was abandoned long ago for rail travel due to its limitations, among them speed and cost.”

Others have pointed out difficulties in procuring the necessary rights of way to build hyperloop tracks (which require long stretches of straight tracks and wide, banking curves to maintain those high speeds) on a commercially viable scale, in much the same way that acquiring private land and NIMBYism (Not In My Backyard opposition) has been one of the biggest roadblocks preventing the Trump administration from building the hundreds of miles of border wall it promised to construct.

“Many infrastructure projects succeed or fail based on right-of-way issues,” Giegel said. “We are designing a system that requires only about half the right-of-way as high-speed rail and can more easily adapt to existing right-of-ways.”

Giegel said that straight tracks aren’t as necessary as critics make them out to be. “We don’t require straight paths to achieve high speeds — the beauty of a hyperloop is that we can bank like an aircraft, meaning we can take tighter turns.”

Apart from land rights issues (and scaling up from a test pod to a commercial pod that can fit up to 28 passengers), Giegel said the main challenge facing hyperloop technology is the same problem any new development faces: regulation.

“As a new mode which transcends the plane, train, and car category, we don’t fit cleanly into the regulatory guidelines of any existing modes,” Giegel said. “We have to demonstrate our safety case to regulators and are committed to work with them to develop a new regulatory framework.”

In her time as the secretary of transportation, Elaine Chao has taken a number of steps to advance innovative methods of transportation developing across the private sector — including hyperloop technology.

In December 2018, the Transportation Department chartered the Nontraditional and Emerging Transportation Technology Council, a body of government officials from the various administrations within the DOT who work to “identify and resolve jurisdictional and regulatory gaps associated with nontraditional and emerging transportation projects.”

In July, the NETT Council published its Pathways to the Future of Transportation report, a 30-page document that outlines which agencies already have sufficient regulatory structures to address emerging technologies and the steps that companies developing innovative transportation technology can take when applying for grants and project approval. Hyperloops are mentioned nearly 20 times.

There are at least three companies in the U.S. developing hyperloops: Virgin Hyperloop, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, and Transpod. They have the benefit of being very similar to maglev and high-speed rails, from the Pennsylvania Maglev Project in Pittsburgh, which was announced in 2001, to the Texas Central high-speed rail that was founded in 2009, and as a result, regulatory guidelines are already in place on which those companies can base their plans.

“There have been very meaningful steps in the hyperloop technology becoming a reality, but there are still a lot of questions that must be addressed about the sustained safety and economics of the technology and operations,” a DOT spokesperson told the Washington Examiner. “The Department remains committed to ensure that the Federal government will be a partner for first and foremost, safety, and innovation.”

Giegel thinks that support will continue no matter which party controls the levers of federal power. “We have support from both sides of the aisle,” he said, “and that gives me great confidence.”

By many metrics, Virgin Hyperloop is the furthest along in realizing a commercially viable hyperloop. In addition to being the first company to send passengers on a test ride, it has already announced 11 projects across the U.S. — in Missouri, Ohio, the Midwest, Texas, and North Carolina.

All of those projects have one thing in common: They’re don’t run along either coast, notably along the so-called Northeast Corridor, one of the most traveled stretches of road, rail, and air in the U.S. stretching from Washington, D.C., to Boston.

For Giegel, the decision was intentional.

Virgin Hyperloop is about connecting the U.S. in areas that don’t already have robust mass transit opportunities: “We aren’t just about connecting the coasts, but actually the whole country — from coast to coast,” Giegiel said. “We’re talking about the heartland of America. And in these areas, hyperloop represents an opportunity to leapfrog. The Northeast Corridor is already served by many forms of transit, which comes with both benefits and challenges.”

“That being said, we’d love to have a Northeast Corridor hyperloop project in the future,” Giegel added.

The U.S. heartland has particular appeal — the planned route in Missouri, from Kansas City to St. Louis, is relatively flat, helping keep costs for building hundreds of miles of brand-new transportation infrastructure comparatively lower than construction in other areas. Initial estimates for the Missouri route, running along I-70, show the cost of building a hyperloop system at anywhere from $30 million to $40 million per mile of track, putting the proposed 250-mile track in the range of $7 billion to $10 billion.

The other challenge facing hyperloop technology? A culture that has prioritized air travel, suburban sprawl, and the independence of the automobile over the railways of Europe.

There were more than 800 million passengers on domestic flights alone in the U.S. in 2019. The U.S. has more domestic passengers in a single year than all flights within the European Union combined — at just roughly 515 million across all 27 EU states.

Comparatively, the U.S. notched 32 billion passenger miles in 2019 — a figure equivalent to the sum of all passengers divided by the total distance traveled by every train. In the EU, France alone completed more than 112 billion passenger miles, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The trick to persuading travelers in the U.S., Giegel said, is to find the sweet spot between travel time, cost, and distance.

“A recent study found that a hyperloop connection between Columbus, Chicago, and Pittsburgh, that would cut travel times from Pittsburgh to Columbus to about 20 minutes, versus three hours by car,” Giegel said — a distance too short to justify a plane ticket but just long enough that a car ride is inconvenient. And Giegel says that hyperloop can make the trip at a cost point comparable to driving than flying.

Giegel said that hyperloop could get passengers from Pittsburgh to Columbus for $33. That’s more than the cost of gas, at just under $20 considering the current average gas price in Pennsylvania, but in one-sixth the speed — turning a full day of driving round trip to a shorter total travel time than the average commute.

Those dividends are even greater at a further distance. Giegel said a hyperloop from Pittsburgh to Chicago would take just 66 minutes and cost under $100. That drive would take more than seven hours in a car — and two hours by plane.

Despite the enthusiasm in the private sector and the regulatory clarifications from the federal government, even Virgin Hyperloop has projected that the first commercial hyperloop won’t run until 2030. Without a product generating revenue, Giegel said he’s thankful for patient investors. He thinks that support from investors, lawmakers, and the public imagination will be enough to fuel those projects to completion.

“Hyperloop is an opportunity for the U.S. to once again lead the world in transportation, create thousands of high-quality jobs, and export the expertise all around the world,” Giegel said.

Now that Virgin Hyperloop has completed its first manned test, Giegel said the company is turning its focus to certification and the regulatory process.

“We just announced a few months ago that West Virginia will be home to the global Hyperloop Certification Center,” Giegel said. “The HCC will pave the way for the certification of hyperloop systems in the U.S. and around the world — the first step towards commercial projects.”

For Giegel, the HCC will be where regulators from around the world gather to establish industrial standards for the nascent transportation technology.

“Right here on American soil, setting the stage for the next new mode of transportation,” Giegel said.