Steffeny “Stet” Frazier, a 51-year-old former crack cocaine dealer, says he “most definitely” will vote for President Trump next year if he’s not returned to prison to complete a life sentence that was ended in August under the Trump-signed First Step Act.

Frazier, an outspoken Trump supporter and father of eight, the youngest born after his arrest at age 26, is among a handful of people released under the new law who now risk being returned to prison as prosecutors appeal the release of some large-scale crack dealers.

Frazier’s supporters say his case is a potential injustice and want prosecutors to drop the appeal. Briefs are due this month to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, but Frazier’s case may ultimately hinge on two similar cases that are further along.

“He will go back to prison if it’s resolved against us,” said Randy Murrell, the federal public defender in northern Florida who is representing Frazier.

Most U.S. attorneys aren’t appealing releases, advocates say, but prosecutors in northern Florida cited approval from the U.S. solicitor general and argue Frazier is among the highest-tier dealers and was ineligible for release.

Mark Osler, a St. Thomas School of Law professor, says other legal fights are emerging around the country. “It’s pretty clear the intent of Congress in this was to broadly give relief to people sentenced for crack, and it’s disappointing to see the Justice Department taking a hard line,” Osler said.

Frazier was released by the same judge who sentenced him during the 1990s crack epidemic, which yielded harsh penalties for dealers, most of whom were black. U.S. District Judge William Stafford found the First Step Act applies, arguing the text of the indictment is more important than the drug quantity proven at trial, and that “Frazier would not be a danger to the community.” Stafford cited a prison case manager’s report detailing Frazier’s “impeccable record of programming and outstanding behavior” and calling him a “prime example of hope.”

Less than two weeks after his release, Frazier appeared on black conservative author David J. Harris, Jr.’s webcast and praised Trump, saying he did more for people in prison than any other president. “On the news several times, I have thanked President Trump a number of times; I have praised him,” he told the Washington Examiner.

Frazier was released because the new law retroactively applied a 2010 law reducing the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences from 100:1 to 18:1.

“My family will vote for President Trump as well. Because of President Trump — he gave me a chance. I know people get caught up in their emotions and all, but he gave me a chance no other president did,” Frazier said. “Everyone uses the campaign rhetoric and slogans, and when they get into office, they don’t do what they say they will do … He didn’t even campaign on what he would do for those of us incarcerated.”

Frazier, currently living with family in southern Georgia, said fellow African Americans are surprised when he discusses Trump. “A lot of them are literally shocked and say, ‘holy — President Trump did that?’ They are literally shocked,” he said.

Although many crack sentences were shortened by President Barack Obama through executive clemency, Frazier was denied. He says he was referred to as a female in paperwork, suggesting his case wasn’t evaluated carefully.

Frazier is scheduled to speak Saturday at pro-Trump Turning Point USA’s Black Leadership Summit and at an October conference in Miami.

Though he isn’t currently asking Trump for a pardon or commutation, Frazier may benefit from allies close to the White House. He’s an adviser to the American King Foundation, run by author and reality TV star Angela Stanton-King and associated with Martin Luther King, Jr.’s politically conservative niece Alveda King.

Another frequent White House visitor, CAN-DO Foundation founder Amy Povah, said, “Stet is precisely the kind of person who deserves relief. I’m shocked that his prosecutor may oppose his release, using our tax dollars to send a man back to prison who is already doing so much for his community.”

Several of his new neighbors in southern Georgia say it would be unfortunate for Frazier to return to prison.

Mitchell County Schools superintendent Robert Adams has booked Frazier to speak at a Nov. 2 community event. He and Frazier have discussed classroom talks and, after Thanksgiving break, an address to nearly 1,000 students in a school gymnasium. “He has an awesome story to tell our students, who are predominately African American,” Adams said. “These days there are a lot of things going on with students and gangs … When you hear from someone who has been through what Mr. Frazier has been through, it makes it real.”

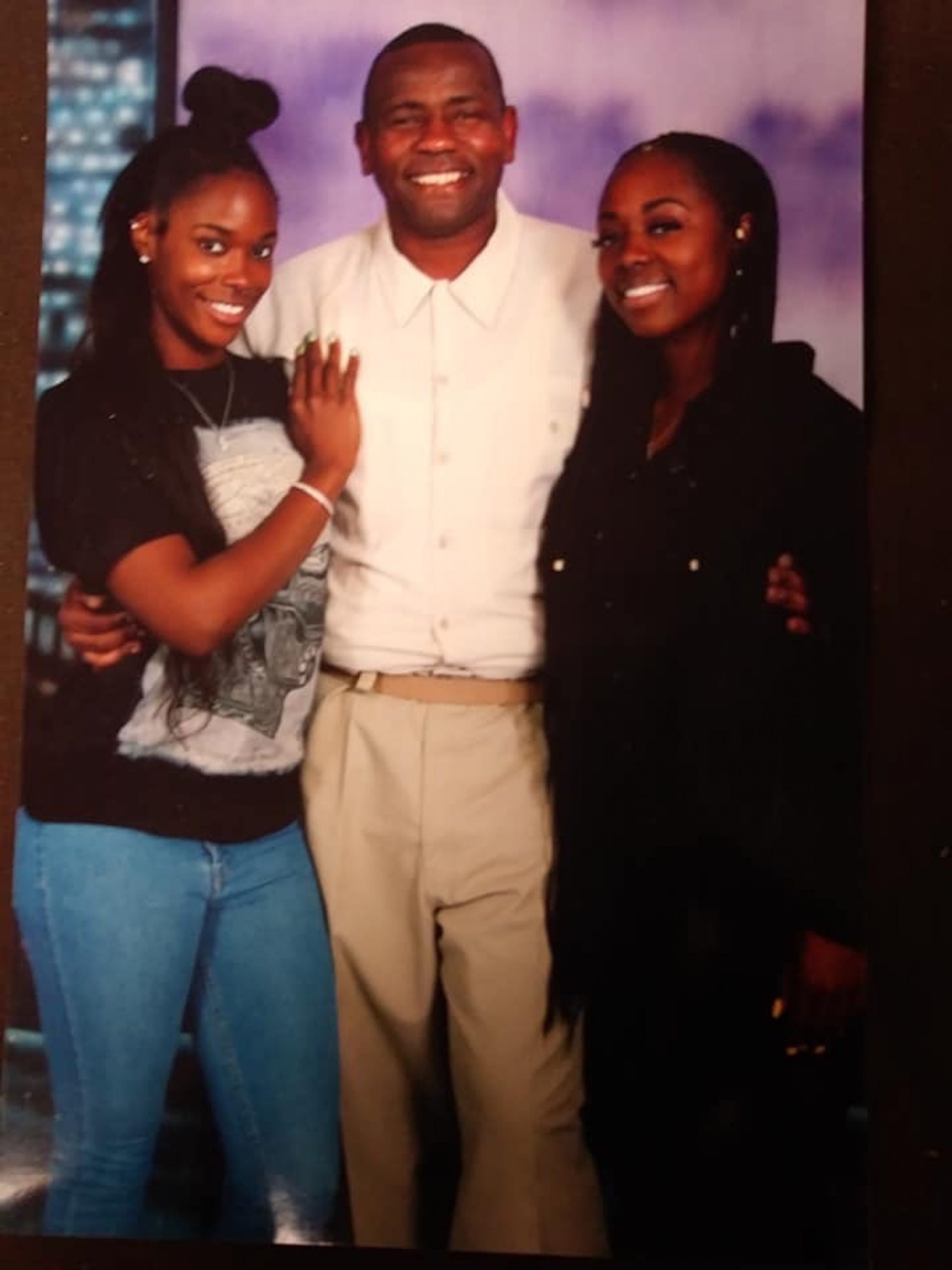

Frazier shared a photo of himself with the local police force’s anti-gang unit and has spoken with the state’s juvenile justice authorities about mentoring youth.

“Based on what he says, he seems to be pretty committed … He’s been pretty busy since he’s been out,” said Keith Jones, director of reentry services at the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Tallahassee, Florida, defended its appeal.

“The United States Attorney’s Office carefully determines whether to appeal adverse First Step Act orders on a case-by-case basis, weighing the mitigating and aggravating circumstances in each case,” the office said in a statement. “Mr. Frazier’s case was appealed only after a thorough review by the Office, the Department of Justice’s Criminal Division, as well as the Office of the Solicitor General, all of which authorized this appeal.”