With the NFL about to start, predictions are everywhere. TMQ’s Super Bowl picks come at the end of this column—along with the disclaimer, All Predictions Wrong or Your Money Back.

Of course most sports predictions are off. Woe onto the New England Patriots, whom Sports Illustrated just picked to win the Super Bowl. SI’s two previous season-eve Super Bowl picks, Ravens in 2015 and Cardinals in 2016, failed to make the playoffs.

The NFL’s own website just ran 14 sets of dueling Super Bowl forecasts—will any of them prove correct? The Miami Herald just predicted the final score of every Dolphins contest. Will even one of these 16 predictions hit the mark? Probably not Dolphins 21, Broncos 18 on December 3, as 21-18 is a rare final score.

Trying to envisage exact outcomes, generally a fool’s errand, veers further into the margins as American society has gone gaga for predictions grounded in data analytics. This field can be useful, but is oversold. If an estimate is precise—especially if it has decimal points!—it is presumed scientific. Yet many decimal-point analytics in sports, politics, finance, and other subjects convert guesses, whether educated or wild, into fuzzy pseudo-information with little value beyond amusement.

According to ESPN, this season the Pittsburgh Steelers will win 10.1 games. Not 10 games, but 10.1 games. This sounds like the determination of some Silicon Valley supercomputer. Actually, it’s preposterous jabber. ESPN goes on to foresee that the Eagles have a 19.3 percent chance to win their division while the rival Giants have a 22.6 percent chance. That’s 3.3 percent better, a conclusion of super-advanced analytics! The Panthers, ESPN foretells, will win 8.8 games while the Buccaneers win 7.7; good on those Panthers for getting 1.1 more victories. The Raiders, it’s sad to report to Bay Area fans, have only a 4.3 percent chance of winning the Super Bowl. Not a small chance, but a 4.3 percent chance: a hyper-specific forecast that surely must derive from big data and lengthy algorithms. Though rest assured, Bay Area, the Raiders do possess a 0.2 percent better chance of winning the Super Bowl than the Chiefs.

A moment before halftime of the Falcons-Patriots Super Bowl, charts from Five Thirty Eight—very scientific looking charts—declared the Falcons “96.6 percent” likely to win, though at that juncture there was just as much time available to New England for a comeback as the Falcons had consumed to get ahead. “When the Patriots were forced to settle for a field goal to make the score 28-12 with 9:44 to go in regulation, their win probability was 0.1%, according to pro-football-reference.com,” the Houston Press reported. “Win probability” to a decimal place—that looks very scientific.

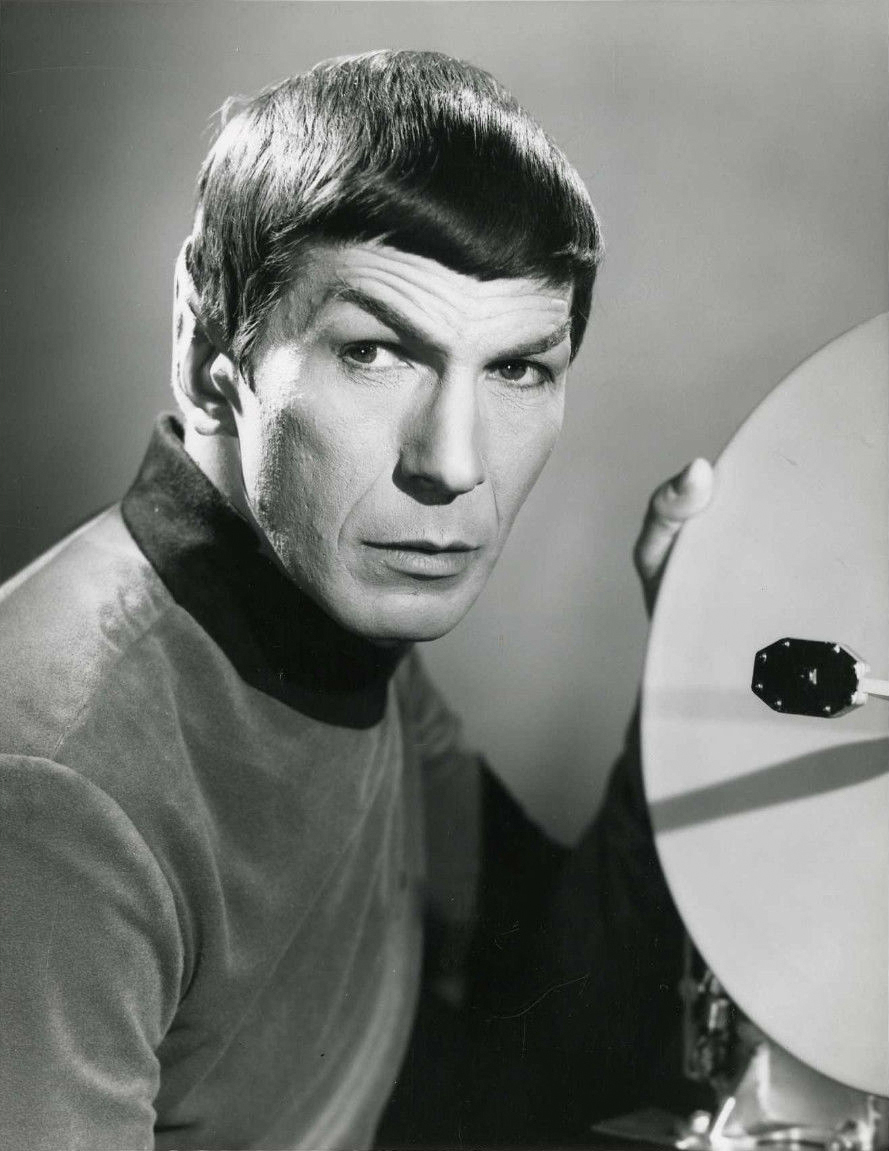

Half a century ago, Mr. Spock planted into American culture the notion that really smart people can say things like, “There is an 89.7 percent chance a reverse tachyon pulse will counteract the zorgon beam in the nebula.” Now precise-sounding predictions are widely assumed not only to have value but to be evidence of sophistication. In sports, no harm is done. What happens when such assumptions cross over into serious matters?

Last August, as the presidential race went full throttle, Nate Silver of Five Thirty Eight declared Donald Trump had “a 13 percent chance of winning the election.” Not a long-shot possibility, a “13 percent chance.” Sounds reassuringly scientific, doesn’t it? Soon Five Thirty Eight would be pretending to possess scientific accuracy about the presidential contest down to the tenths of a percent. Months after the calamity of the Trump election, Hillary Clinton would declare, referring to the James Comey letter of October 27, “Nate Silver, who [is] considered to be very reliable, has concluded that if the election had been on October 27, I’d be your president.”

Let’s set aside whether a Clinton victory would have been good for the nation: Her candidacy was heavy with negatives. Let’s set aside whether Silver and his staff, who have been right on many occasions and wrong on many others—they said Clinton had a “greater than 99 percent chance” of taking the Michigan primary, which she lost—should be viewed as “very reliable.” Coin tosses are reliable half the time. Let’s stick to the issue of whether claims such as “4.3 percent chance of winning the Super Bowl” or “13 percent chance” of winning the presidency have any meaning at all, or simply are entertainment, dressed up to appear to be science.

Here’s a fast-forward version of Five Thirty Eight predictions about the 2016 presidential vote. In June 2016, Silver said Hillary had an “80.2 percent” likelihood of winning—not 80 percent, 80.2 percent. By July 24, Silver had Clinton down to a “58.3 percent” chance. Two days later on July 26, she was down to “53.3 percent.” A week later Clinton had zoomed to “79.9 percent” likelihood—quite a rapid rise, perhaps owing to one of Five Thirty Eight’s infamous “adjustments.” By late August, Silver had Clinton at “87.7 percent” likely to win, by mid-September at “66.8 percent,” and by mid-October at “82.2 percent.” The day before the vote, the website said Clinton had a “68.5 percent” win probability; the morning of the election, it was “71.4 percent.”

This is a gloss, but you get the idea. Five Thirty Eight had Clinton’s odds rising and falling on a nearly daily basis, as if the election were the NASDAQ—though it is extremely difficult to believe there were bona-fide alterations in voter sentiment of the speed and magnitude claimed, as this would have required tens of millions of people changing their minds again and again and again. What Silver was reporting was daily small fluctuations in guesses.

He wasn’t alone. The New York Times, cable news channels, the Huffington Post, and other organizations offered an almost day-by-day series of presidential election speculations dressed up in graphics that made them seem to be the scientific discoveries of great researchers, rather than what they were: guesses, however educated. In mid-July, the Times had Clinton with a 76 percent chance of victory. In six days she fell to 69 percent. A month later she was at 87 percent in the morning, rising to 88 percent that afternoon. (Millions of voters must have said at lunch, “This burrito is good, so now I’m voting Hillary.”) By mid-September, the Times had Clinton down to 79 percent, then down to 74 percent in mid-October. For the final week before the vote, the newspaper put Clinton at 84 percent.

The point is not that all these forecasts were wrong. Practically everyone was incorrect about November 8, 2016; if I’d posted a prediction I would have been utterly wrong. The point is that the prediction numbers on Five Thirty Eight and similar places appeared to be the result of deep dives into data, yet were darts-on-a-board exercises gussied up with charts, graphs, and squiggly lines to make them professorial.

Did the public impression of a scientifically-proven, certain Clinton walkover convince many people to not bother voting? We’ll never know for sure, but this seems plausible among the data-conscious young, whose miserable turnout—46 percent of those to age 18 to 29 voted in the 2016 presidential race, versus 71 percent of seniors—likely was a larger influence on Trump’s win than anything done by those pesky Russians. The Princeton Election Consortium, which is only loosely associated with Princeton University but enjoys the school’s glistening reflection, said just before the vote that Clinton was “more than 95 percent” assured of victory, with an “83.5 percent” chance Clinton would carry Wisconsin, which of course she lost. These and other faux-precise predictions could have sounded like assurance there was no need to get out and vote.

The situation became so ridiculous that the Huffington Post, which shortly before the vote called Clinton 98 percent likely to win, angrily denounced Five Thirty Eight merely for Silver’s caution that a Trump win was not out of the question—the HuffPo acting as though if Hillary won the predictions, she’d win the office.

Electoral College prognostications were as far off as vote forecasts. The election oracle Larry Sabato, who bills himself as the possessor of a crystal ball, said in August that Clinton would win with exactly 348 electoral votes. Doesn’t that sound reassuringly specific! She received 232. “We’ve heard from many of you asking why we haven’t switched Arizona and Georgia to Clinton,” Sabato wrote—as though if Hillary won the predictions, she’d win the office.

“Clinton losing the election and the Falcons losing the game is . . . not logical.”

In July, Five Thirty Eight had Clinton receiving “279.1” electoral votes, an outcome that was not possible, but had the desired faux-scientific ring. Silver foresaw libertarian Gary Johnson snagging “0.6” votes in the Electoral College. By August, Silver had Clinton up to “341.7” electoral votes compared to “0.3” for Johnson. Clinton rose in August to a projected “364.5” electoral votes, and then fell two days later to “358.2”—something must have happened in just two days that cost her 6.3 electoral votes! And needless to say, no forecaster predicted the electoral ballot cast for Faith Spotted Eagle.

Defenders of faux-specific predictions would say that “341.7 electoral votes” or “8.8 victories” are not intended to suggest real outcomes, and rather are artifacts of incredible analytical exactitude. But analytics that produce impossible outcomes are not advanced and impressive, they are spurious. Many such analytics consist of multiplying or dividing estimates, then treating the result as precise.

After predicting Trump would not win the Republican nomination, Silver was honest enough to admit how far off he was—but attributed the error to his staff “acting like pundits,” rather than like statisticians.

In the Five Thirty Eight world, pundits are awful people who substitute their opinions for rigorous science. Yet practically everything on Five Thirty Eight is punditry! Often, it’s insightful punditry that is well worth the reader’s time. But in some ways it’s more pernicious than the newspaper columnist or TV presenter who pretends that his or her opinions are not merely interesting or worthwhile, but the voice of abstract truth. The patina of science in decimal-place predictions distracts us from awareness that what is being received is not verity, but rather entertainment. Ideally, readers check back every day to see if the numbers—the meaningless conjectures—are changing. Numbers vacillating every day is entertaining.

By May 2017, CNN hosts Alisyn Camerota and Chris Cuomo cited Nate Silver as source authority for the claim that Hillary Clinton would be president were it not for the bizarre Comey letter. Mr. Spock would never fall for that! All that Five Thirty Eight, or any forecasting service, produced before November 8, 2016, was a bunch of intriguing guesses: guesses that became one of the reasons Trump is in the Oval Office. What a relief sports predictions cannot backfire in such a manner.

Stats of the Season Start #1. Last season was the fifth time Drew Brees threw for at least 5,000 yards. All other quarterbacks in NFL history combined have thrown for 5,000 yards a total of four times.

Stats of the Season Start #2. Will Deshaun Watson be under center for Houston at New England in Week Three? At Gillette Field, Bill Belichick is 8-0 versus rookie quarterbacks.

Stats of the Season Start #3. Joe Flacco is 6-0 against the Dolphins, who visit Baltimore just before Halloween.

Stats of the Season Start #4. Since 2014, the Rams are 4-2 versus Seattle, but 13-29 versus all other teams.

Stats of the Season Start #5. In the 2004 draft, Cleveland passed on the Ohio-born Ben Roethlisberger, who is now 20-2 versus the Browns.

Stats of the Season Start #6. Roethlisberger’s Steelers open at Cleveland, which is on a 0-12 streak in season openers.

Stats of the Season Start #7. The Lions are on a 1-16 stretch versus the Packers in Wisconsin.

Stats of the Season Start #8. The Lions are on a 3-16 stretch versus the Vikings in Minnesota.

Stats of the Season Start #9. On Thursday, the Chiefs face the defending champions in the opener; Tom Brady is 10-0 in Thursday games.

Stats of the Season Start #10. In New England’s two most recent Super Bowls, the Patriots fell behind 17-52, and then outscored their opponents 45-0, including outscoring Seattle and Atlanta 39-0 in the fourth quarter and overtime.

They Saved the Best for Last. As David Leonhardt has noted, many sports seasons of late have come down to a fantastic finish: Cleveland back from a 3-1 deficit in the 2016 NBA Finals, the Chicago Cubs back from a 3-1 deficit in the 2017 World Series, the 2016 last-shot victory of underdog Villanova over North Carolina for the men’s college basketball title, underdog Clemson’s last-second victory over Alabama for the major-college football title. Any Broadway producer knows the rule: Save the best for last. New England honored sports lore by saving the best for last. Just when I thought our chance had passed/you went and saved the best for last: This should have played over the stadium loudspeakers as the Super Bowl overtime concluded.

Why NFL Fourth Quarters Are Interesting. All five New England Super Bowl victories under Tom Brady have been by less than a touchdown. Last season, six of the 10 Panthers losses were by a field-goal margin. As the new season cranks up, you’re sure to hear, “Team X played in a lot of close games last year.”

That’s because everybody in the NFL plays in a lot of close games. In 2016, 53 percent of NFL contests were decided by a touchdown or less; 24 percent by a field goal or less. The share of close games has steadily risen since the merger, as dynasty teams have become fewer and free agency spreads talent more evenly. Contrast this to big-college football, where blowouts are frequent.

Hank Williams Back—Really? TMQ readers know my compromise with my Baptist upbringing is to be pro-topless but anti-gambling. There will be more on the latter, at least, as the season progresses. If you insist on throwing $5 into a workplace pool, pick the Seahawks when Atlanta visits Seattle November 20 on Monday Night Football. Not only are the current Blue Men Group the league’s hardest team to defeat at home: Seattle enters the season with the best Monday Night Football winning record (23-8, .742) while Atlanta enters with the worst Monday Night Football record (12-27, .308).

In addition to this contest representing a conjunction as powerful as that of Tarva and Alambil in Prince Caspian, the Seahawks achieved home Monday Night Football victories in 2012 and 2015 when officials made last-second bad calls in their favor: the Fail Mary game versus Green Bay in 2012, then failure to flag “batting” against the home team on the decisive down versus Detroit in 2015.

The 49ers have the most Monday Night Football wins, at 48 against 25 losses. Dallas (45-33), Pittsburgh (44-23), Oakland (38-27), and Indianapolis (23-16) perennially play well on Mondays. The Bears and Broncos are tied for most Monday losses, at 30-37 and 31-37, respectively. Cincinnati is nearly as bad at Atlanta, at 11-23 on the first day of the work week.

League schedule-makers did the Potomac Drainage Basin Indigenous Persons a huge favor by giving them only away Monday Night Football dates in 2017. The R*dsk*ns are on a miserable 1-16 stretch at home under the lights on Monday, “a stretch that includes the entire Dan Snyder era.”

It was Doctor Cornelius who advised football fans to look well upon the Falcons and Seahawks, who will pass within one degree of each other November 20. (YouTube/Disney)

Other Places for Your $5. The Eagles and Denver have the league’s best records in the game after the bye, 21-7. Following this autumn’s bye, Philadelphia is at Dallas; following its bye, Denver hosts the Giants. Cincinnati has the league’s worst after-bye record, at 8-19-1. Following this autumn’s bye, the Trick-or-Treats travel to the Giants.

Astronomers Overhear the Millennium Falcon Calling the Rebel Base on Endor. Reader Steven Schwankert of Beijing notes this finding of five fast radio bursts emanating from an unknown source, designated FRB 121102, in a distant galaxy. Radio astronomers puzzle over fast radio bursts from deep space; cosmologists puzzle over gamma-ray bursts of distant origin. The standard assumption is that both must have natural causes that so far are unknown.

What if fast radio bursts are a form of communication? If gamma bursts are the muzzle flashes of interstellar combat?

Because space aliens are associated with Hollywood nonsense, wondering who’s out there tends to be seen as ufology: Everything must have a natural explanation. But it seems improbable that in a cosmos of two trillion galaxies (that’s the latest estimate), Earth is the sole place where intelligence has arisen. Even if, as it appears so far, there will never be a practical means for interstellar travel, radio communication with another civilization could have practical value (exchange of technical ideas) and profound impact on our culture (if other worlds have no idea what religion is, or, alternatively, hold beliefs similar to ours, either would be an eye-opener). Here is your columnist on this subject decades ago. Little in this essay has changed, beyond the estimate of total galaxies and that “exoplanets” are now being discovered.

What’s that, Han? You’re trying to tell us you made the Kessel Run in how many parsecs? (YouTube/20th Century Fox)

Setting Expectations Low—Football Edition. As camps end and the real thing approaches, NFL coaches complain about the murderously difficult schedules they face. Like political consultants, coaches want to set expectations low, so anything north of rolling off a log will be perceived as doing better than expected.

One aspect of this is preseason obsession with strength-of-schedule charts. Only two of an NFL team’s 16 regular season opponents are determined based on schedule strength—14 of the matchups (88 percent) are dictated years in advance by formulas unrelated to on-field performance. In turn, NFL teams vary so much year-over-year that the previous season’s performance is little guide to the current season. In 2015, Atlanta finished out of the running, and thus looked meh on the 2016 schedule-strength chart—and of course Atlanta came within a quarter of winning the Lombardi Trophy. There are many similar examples. Jeff Hunter of SBNation shows why anyone trying to project results from the strength-of-schedule chart is wasting their time.

Next in line are annual complaints from coaches, and team faithful, about killer road trips or short weeks. The Bears, for example, play three of their final four dates on the road. That’s so unfair! Midseason they play three of four at home and don’t seem to mind. The Buccaneers host the defending champion Patriots on a Thursday, only four days since their prior outing, then travel to Arizona to play on Mountain West Time. That’s so unfair! But they also get three of their final four at home, and the Patriots must come to them on an equally short four-day week. Every NFL team’s schedule has rough patches and smooth patches. Like players who complain about the calls that went against them while skipping the calls in their favor, NFL coaches draw attention to the hard parts of the schedule whilst whistling a merry tune on the easy parts. It’s all about lowering expectations. Why, they make us play half our games on the road!

In college they sure don’t. The Power Five programs dominate the college scene owing to recruiting power and to gimmick schedules. Here is Kurt Snibbe’s memorable illo of the arrival of Cupcake University at the field of a football factory. Lower-division Howard University, a 45-point underdog, on Saturday defeated UNLV on its own field—Howard had been paid $600,000 to fly out and get clobbered before the home boosters. The D.C. school’s victory became newsworthy because cupcake wins are so rare.

This season Alabama bravely faces off against lower-division Mercer, which last season lost to Wofford and surrendered 52 points to Chattanooga. The situation is analogous to the Indianapolis Colts scheduling Indiana State. To top it off, Alabama has seven homes dates, a neutral-site game, and just four road appearances at a hostile field. At one stretch Alabama plays six of eight at home, with opponents including lower-echelon Fresno State and Colorado State. Ohio State and Clemson in 2017 both will enjoy seven home games and five away dates—this is analogous to the Denver Broncos playing nine games at home and seven on the road. Clemson, college’s defending champion, bravely will face The Citadel, which in 2016 needed overtime to best Samford.

This year’s King of the Gimmick Sked is Florida, which plays eight games at home, one at a neutral site, and only three true road dates. This is the equivalent of the Green Bay Packers having two games at Lambeau Field for each one elsewhere.

Yet They Came Cryin’. In May 2014, a powerful warning about Donald Trump appeared: “If you believe anything Trump says on any topic, don’t come cryin’ later.” Where was the warning—in the New Yorker? At a forum of the Council on Foreign Relations? It was on ESPN! Specifically, in TMQ.

Rule Changes for 2017. The timed leap to block a field goal is no longer legal, and regular season overtime ends after 10 minutes, not 15. Extending defenseless player protection to receivers who don’t have the ball is a great idea, though the NFL insists on saying the protection applies to the “head or neck area.” (Which differs from the head or neck how, exactly?) This year’s officiating “point of emphasis” on downfield contact between defensive backs and receivers is a good idea but sounds like will be hard for officials to enforce on a consistent basis.

Good luck to zebras with the league front office directive to “strictly enforce” penalties involving “low hits on the passer rules designed to protect quarterbacks in the pocket from forcible contact to the knee area or below. Driving the shoulder, chest or forearm into a quarterback’s knees or below will be a foul.” So defenders can’t hit a quarterback low, can’t contact the quarterback’s helmet or “neck area,” can’t grab the back of the quarterback’s shoulder pads, can’t use their own chests for contact, and can’t launch themselves into the quarterback. How, exactly, are you supposed to tackle the guy legally?

Maybe Continuity Is Overrated. Bill Belichick seems to be able to mount winning teams by taking volunteers from the audience. Except at quarterback, the Patriots’ roster exhibits considerable turmoil, yet since Belichick arrived at New England in 2000, the Patriots have reached the postseason 14 of 17 possible times. And perhaps you have heard about that Super Bowl thing. On the low end of this scale, the Browns (Version 2.0) resumed in Cleveland in 1999, and since then have had one postseason appearance in 18 possible times. DeShone Kizer will be the Browns’ 15th opening-day quarterback in 19 seasons, and 27th starting quarterback in that span. Hue Jackson is the Browns’ ninth head coach in 19 seasons. Perhaps continuity in the NFL is not overrated.

Maybe Sacks Are Overrated. This column contends that the clang of an incompletion matters more to contemporary NFL defense than sacks. Announcers extol sacks because they are dramatic, and general managers reward sack artists with bonuses. Often those selfsame sack artists don’t contain the run, or let themselves be pushed upfield, out of the play, as they sell out for sack glory. Check last season’s stats—six of the eight top teams for total sacks failed to reach the playoffs.

CMGI Field Sounded Like It Was Named After a Blood Protein. In the opening-weekend Monday Night Football doubleheader, the LA/B Chargers will face the Broncos at Sports Authority Field—even though Sports Authority has gone out of business. Five years ago, Deal Book provided one of many warnings against the Naming Rights Curse.

If Your Practice-Squad Quarterback Doesn’t Have Better Stats Than John Elway, Something Is Desperately Wrong. There’s no Colin Kaepernick with the 49ers, but there is the undrafted quarterback Brian Hoyer. This gentleman is now with his seventh NFL team. Ryan Fitzpatrick, the 250th player chosen in his draft year, is now with City of Tampa, also his seventh NFL club. What do they have in common besides the lucky number seven? At 59.5 percent (Hoyer) and 59.7 percent (Fitzpatrick), both oft-waived quarterbacks have better career completion percentages than Terry Bradshaw, Otto Graham, Joe Namath, Bart Starr, Johnny Unitas, and Warren Moon, all Hall of Fame signal-callers.

How the NFL’s rule changes to favor passing offense make even run-of-the-mill quarterbacks seem like Dan Marino will be the subject of an upcoming Tuesday Morning Quarterback.

Thank Goodness the United States Does Not Have, All at the Same Time, a President, Secretary of State, and Secretary of the Treasury Who Have Never Held Public Office. As the new NFL season kicks off, there are four freshman head coaches—and all have never before been a head coach at any level of the sport.

Vance Joseph (Broncos), Anthony Lynn (Chargers), Sean McDermott (Bills), and Sean McVay (Rams) have never been head coaches at the professional, collegiate or prep levels. Yet here they are in charge: Starting at the top is en vogue, not just in Washington, D.C. Twenty-five of the NFL’s 32 head coaches for the 2017 season got their first head coaching assignment at the sport’s highest level. Bruce Arians (Arizona), Bill O’Brien (Houston), Jim Caldwell (Detroit), and Doug Marrone (Jax) had been college head coaches before being handed an NFL whistle, while Jay Gruden (Washington) was a head coach in the Arena League, and Dirk Koetter (Tampa) and Doug Pederson (Eagles), bless ‘em, started as high school head coaches.

Koetter got his big break at Highland High of Pocatello—go Rams! Pederson’s came at Calvary Baptist Academy of Shreveport—go Cavaliers! Gruden’s Arena League team was the Orlando Predators, whose mascot was a space-alien-thing named Klaw. Perhaps better would have been the Craw from the old Get Smart series.

Major-college head coaches who have moved to the NFL generally have not done well: see Chip Kelly, Steve Spurrier, and Dennis Erickson. (Pete Carroll came to the Seahawks from USC, but got his head-coaching start in the NFL, at the Jets.) College head coaches are accustomed to being treated as little gods by the local press and by boosters. They can count on great deference from the unpaid employees—excuse me, I meant to say the college students!—whose scholarship paperwork they control. NFL head coaches by contrast must deal with wealthy stars who have egos that can be tracked on radar. The pro season drags on and on—colleges for the most part don’t play in December—and in the pros, the media knives are always out. This tends to mean that being a coordinator at an NFL franchise is better preparation for becoming an NFL head coach than being a head coach in college.

At the major-college level, most programs start the season with a winning record nearly certain. TMQ contends that Power Five football programs have such advantages in recruiting power and gimmick schedules that an orangutan could get a top program bowl-eligible. At big college programs, winning half your games is rolling-off-a-log easy. In the NFL, a third of teams fail to win half their games. The relative ease, in big-college football, of compiling at least a winning record inflates head coaches’ views of themselves. Those who go on to the NFL discover that the college challenge—Can we hang 50 points on a Division 1AA cupcake?—is replaced by the pro challenge, which is, can we defeat the Jaguars by a field goal?

Is this the next man to lead [YOUR POWER-CONFERENCE SCHOOL HERE] to the Music City Bowl? (Photo credit: Eric Kilby)

For college coaches, 90 percent of the season is determined by recruiting, which consists of tricking gullible 17 year olds and their parents or guardians into believing the cap they choose on signing day is an instant stepping stone to wealth. They do this while distracting the athletes and their parents or guardians from noticing that the overwhelming majority of starters even for national title schools never receive an NFL paycheck, and distracting them especially from the classroom work that would confer tangible economic value in the form of a bachelor’s degree. If recruiting goes well, success on the field in the fall is close to automatic. That is, big-deal college coaching is primarily salesmanship, much of it dishonest.

In the NFL, there’s a little recruiting during free agency, but only a little: Drafted players have no choice but to “commit.” There is more cynicism but less dishonesty than in college: far more Xs-and-Os. Tactics, practice psychology, and film study really matter at the NFL level, where the very best teams possess only a slight talent edge over the very worst. At the Power Five level of college football, the top teams hold a gigantic talent edge; tactics mean little and psychology does not matter because the unpaid employees—I meant the college students!—have no leverage.

These factors add up to college and professional football coaching being fundamentally different. In the end it makes sense that almost all NFL head coaches have come up through the ranks of professional assistants, rather than first being head coaches in college.

On that note . . . Chip Kelly’s Fast-Paced Offense Makes Fast-Paced NFL Exit. The season begins with Chip Kelly unemployed—in football coaching, at least. Maybe he’s making sundaes at a Dairy Queen somewhere. At Philadelphia and then Santa Clara, Kelly managed to be fired twice in a period of 368 days. The 49ers situation was so dysfunctional when he arrived, one can speculate that, as part of the internal power struggle among courtiers in the ownership suite, Kelly was set up to fail. Nevertheless, the former Oregon Duck was 28-36 as an NFL head coach and on a 5-19 stretch when he was cashiered by Santa Clara.

Like Steve Spurrier, Kelly was a college success who entered the NFL thinking his offensive theories would be unstoppable, and learned otherwise. Adored by the college-town press and flattered by boosters who want access to the sideline, Power Five coaches can view themselves as super-geniuses. Kelly’s NFL career peaked in his very first game, when the Nesharim jumped to a 33-7 lead over the R*dsk*ns on Monday Night Football. Everything was downhill from there, as pro defensive coordinators learned to contain the Blur Offense, while Kelly revealed himself as inept at trading, drafting, and understanding the national media.

Marx Warned, “Capitalism Will Sell the Personal Seat License Used to Bankrupt It.” A court ruling in California last week made it easier for professional sports leagues to reach into the pockets of Golden State taxpayers to build new football, basketball, and baseball facilities: places where the public provides the capital and bears the risk, while all profit is private. If stadia interest you, get the terrific new book The Arena, by Rafi Kohan, a wonderfully entertaining look behind the scoreboard at many of the nation’s high-profile sports facilities.

The Football Gods Winced. Last Christmas Day, Kansas City led Denver 27-10 with 1:52 remaining, and the Chiefs faced 3rd-and-goal at the Broncos 2. Rather than run straight ahead—or simply kneel—Andy Reid put defensive tackle Dontari Poe in at quarterback, where he faked a dive then lofted a pass into the end zone. Listed at 346 pounds and likely substantially more embonpoint, Poe may be the heaviest person ever to throw an NFL touchdown pass. Kansas City fans got a chuckle, YouTube got a highlight. But what was the point of taunting an opponent the Chiefs face twice a year? If the AFC West comes down to the final week of the 2017 regular season—Chiefs at Broncos on New Year’s Eve—Kansas City may be mighty sorry for providing Denver with extra motivation.

Politicians Decry Inequality, Then Use State Lottos to Increase It. The NFL is up to about $14 billion a year in revenue, making the $1 billion or so a year in public subsidies the league receives even more offensive than before. Not content to rob taxpayers, the NFL also inveigles the poor into throwing away what little they possess via NFL-branded scratch-off state lottos, such as this.

After last week’s big Powerball prize, Arthur Brooks of the American Enterprise Institute spelled out how state-run lotteries deceive low-income persons with glittering promises of one-in-a-zillion chances at wealth. Years ago at ESPN, yours truly showed the crooked web of interactions among the NFL and state governments that want money to squander, and how they work in tandem to fleece the poor. Beyond the repulsive nature of politicians who claim to care about inequality using the lottery ruse to harm the lives of disadvantaged men and women, yours truly noted: “TMQ’s law of money holds that it would be really great to get $1 million, while getting $100 million would ruin your life. The lottery mindset of vast amounts conferred on few, while the majority suffers, is everything that’s wrong with American materialism in a nutshell.”

NFL Tanking Update. Two weeks ago TMQ noted the Browns, the league’s worst team, have been squirreling away future draft picks rather than trying to win in 2017. Last week they waived former Pro Bowler Joe Haden—didn’t trade him, just gave him the old heave-ho. The Pittsburgh Steelers, who pound the Browns relentlessly—they’re 30-5 against their AFC North “rival” this century—quickly signed the cornerback, who now has a great chance of starting in the playoffs whilst his former teammates have a great chance to dress like Tootsie Rolls. Haden to Pittsburgh satisfied the Steelers’ desire to win, and also satisfied the desire of the Browns front office to tank.

What about the Buffalo Bills? Two weeks ago TMQ noted they are maneuvering to rival the Browns’ planned-obsolescence scheme. Sure enough, as Haden was being waived, the Bills took another step to ensure loss after loss. Buffalo traded linebacker Reggie Ragland to Kansas City for a 2019 fourth-round selection. At least it’s a trade, not a pure giveaway. But consider the details.

In NFL draft transactions, a current choice is worth a future pick minus one round per year—sort of discounting to present value. For example, in the latest draft, the 49ers swapped their 2017 third-round choice to New Orleans for the Saints’ second-round selection in 2018. The future pick, a second-rounder, minus one round per year, equaled a current third-rounder.

The pick Buffalo acquired from the Chiefs doesn’t come for two years, and thus discounts to a sixth-round selection. In the 2016 draft the Bills spent a second-round choice and two fourth-round picks to acquire Ragland, who ended up injured for his rookie season. All this means that in a short space of time, Buffalo traded one second-round and two fourth-round choices for a sixth-round choice, without ever letting the player involved so much as step onto the field. Wondering how an NFL team goes 17 consecutive seasons without reaching the playoffs? This is how.

Last week TMQ noted that a theme to be developed this season is that NFL coaches and owners don’t necessarily want to win. Winning is a nice bonus, but many coaches are concerned primarily with postponing the day on which they are fired, losing jobs that pay millions of dollars a year for what high school coaches do for nearly free. Many owners, meanwhile, simply want to rake in the proceeds of public subsidies. In order to maintain appearances, NFL owners and management personnel generally pretend to be trying to win. In Buffalo, Bills owners Terry and Kim Pagula aren’t even bothering to go through the motions. Two weeks ago—before the Ragland trade—TMQ supposed Bills management was setting up the question, “How can you possibly expect us to win in 2017?” Now Bills management has set up, “How can you possibly expect us to win in 2018?”

Don’t Count on New England or Atlanta in Minneapolis. Of the 51 Super Bowl entrants, 15 winners, and 14 losers, failed to reach the playoffs the following season. Last season neither of the previous Super Bowl entrants, the Broncos and Panthers, made the playoffs. This season, will either the Patriots or the Falcons—now the Epic Fails to TMQ—receive a postseason engraved invitation?

A central difference between the NFL and NBA is that championship-round pro basketball teams almost always reach the playoffs the following year. This is partly because 16 of 30 NBA clubs (53 percent) receive postseason invites, while 12 of 32 NFL teams (38 percent) do so.

But it’s also partly because the pro basketball requirement for reaching the title round is a few exceptional athletes who play well night after night in an 82-game season that tends to wash out the effects of chance. The football requirement for reaching the Super Bowl is two dozen or more quality athletes who perform under shorter-term deals, in a 16-game season where random bounces of the ball determine some outcomes. In the NFL, one game determined by a fumble, or by an officiating decision, changes 6 percent of the team’s result for the season; in the NBA, a bad late call or crazy off-balance three at the buzzer changes 1 percent of the season result.

The four most recent Super Bowls have featured a total of six appearances by Denver, New England, and Seattle. That’s three teams attaining six of the eight possible slots in the period, showing how strong these clubs have been recently compared to all others. But the last time a Super Bowl entrant made the contest in back-to-back years was the Patriots in 2005, versus the Eagles, after Patriots versus Panthers in 2004. However good New England and Atlanta may be in 2017, the odds are against either returning to the Super Bowl in February.

Someone may have to call in Coach Gaines for a halftime speech in this year’s Super Bowl. (YouTube/Universal Pictures)

TMQ Super Bowl Prediction. Texas is the center of gridiron culture, yet when Super Bowl LII kicks off at VI:XX Eastern on February 4 in Minneapolis, it will have been 22 years since a Lone Star State team appeared in the ultimate contest. TMQ foresees a Friday Night Lights-inspired Texas-forever pairing: Houston versus Dallas. That’s if the Texans can get past the Patriots, who last season defeated Houston twice, by a combined 61-16.

My alternative-jersey Super Bowl prediction is Packers versus Raiders. The Patriots may be the NFL’s best team but their luck has to run out. Right? Umm, right?

This prediction is not in any way scientific, especially since it forecasts four teams into two slots. Many touts offer multiple, mutually contradictory forecasts and then if one is correct say, “See, I predicted it!” What a scam! Wait, that’s what I just did.

Next Week. The football artificial universe resumes, not a moment too soon.