Cuban exile Antonio “Tony” Bascaro is preparing to leave federal prison, where he has spent most of his adult life serving the nation’s longest-known stretch for dealing marijuana. But the 84-year-old fears trading one cell for another.

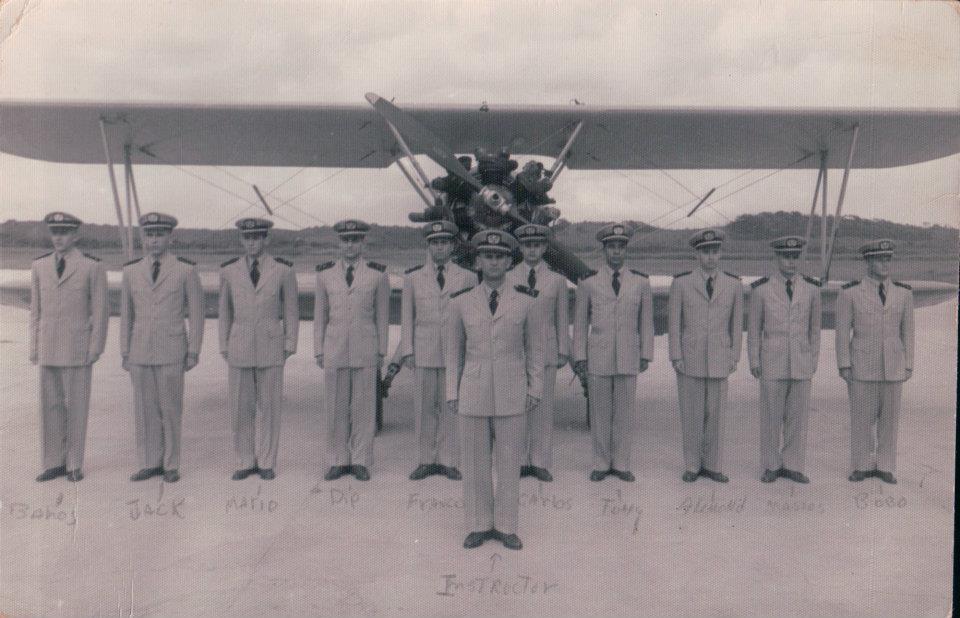

That’s because Bascaro, a pilot who trained for the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, is not a U.S. citizen and risks being detained and ejected from the country upon release. Bascaro says if he’s returned to Cuba, he could spend the rest of his life as a political prisoner.

“My life will be in jeopardy, if deported,” Bascaro told the Washington Examiner from a federal prison in Miami. “But by experience, I’m ready [for] anything that may happen at my release.”

Bascaro, who now walks with a cane, was arrested in 1980 for helping import more than a half-million pounds of pot, using his aviation skills to scout landing sites along Florida’s coast. He was sentenced to 60 years in prison but will get out after about 40 for good behavior.

With about 100 days left in prison, Bascaro isn’t sure what’s next. He is scheduled to leave prison on June 8 but must report to the local U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement office on June 13.

“I don’t have a lawyer at present, but I’m working on getting one specialized in immigration, within my economical situation, to be with me when I’ll report to ICE,” Bascaro said.

The aging exile has no immediate family in Cuba and contends it would violate international law to deport him to Cuba — or anywhere with a significant Cuban government presence.

Legal experts contacted for this story said they would need more information before commenting. A spokesman for ICE in Miami said he could not comment on the case.

Nearly six decades ago, Bascaro was recruited by the CIA to train in Guatemala to overthrow Castro. He was transferred to Nicaragua in preparation for the invasion, launched under the belief that Cuba’s revolutionary government would be toppled with ease.

The invasion quickly turned into a disaster for President John Kennedy’s administration. Bascaro’s plane didn’t leave the ground, as additional air raids were canceled. More than 100 of his comrades were killed, and about 1,200 others taken prisoner over three days.

Bascaro had been recruited in part because of his experience in the 1950s as a military pilot for the government of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, a position for which he was briefly detained after the success of Castro’s revolution in 1959.

The Bay of Pigs Veterans Association confirmed Bascaro’s participation among the exiles who sought to topple Castro, and he is included on a publicly available list of veterans.

After the failed invasion, Bascaro returned to Guatemala and married a local woman before divorcing and joining fellow Cuban exiles in Florida, where he was recruited in the late ‘70s to join a marijuana-smuggling ring.

It was a lucrative but high-risk career. Bascaro told NBC News in 2016 that he earned up to $1 million over two years and bought homes in Miami and Guatemala.

Nickolas Geeker, the former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Florida who served as lead attorney for the prosecution in Bascaro’s trial, said the drug-dealing ring dealt exclusively in marijuana, not harder drugs.

Geeker said he was surprised when informed by a journalist three years ago that Bascaro was still in prison. “I thought probably that by this time, he would have been released,” he recalled.

Jose Luis Acosta, the operation’s ringleader, was released in 1994 after 12 years in prison after cooperating with authorities.

Over the years, Bascaro has attracted media attention for his status as the longest-term pot prisoner, remaining incarcerated even as 10 states have legalized the drug.

Although some people have life sentences for marijuana, Beth Curtis, editor of LifeforPot.com, said nobody currently in prison has served as much time as Bascaro. The second-longest-serving pot prisoner is Calvin Robinson, jailed since 1988.

Despite his long sentence, Bascaro’s clemency application was denied by former President Barack Obama. He was scheduled to enter a halfway house last year, but that was canceled because he is not a citizen. And this year, advocates thought he would be released immediately under the First Step Act, which expanded good-behavior credits, before it became clear the new law only applies to post-1987 crimes.

Familiar with disappointment, Bascaro said, “I will believe my release is real when I see me on the other side of the fences.”

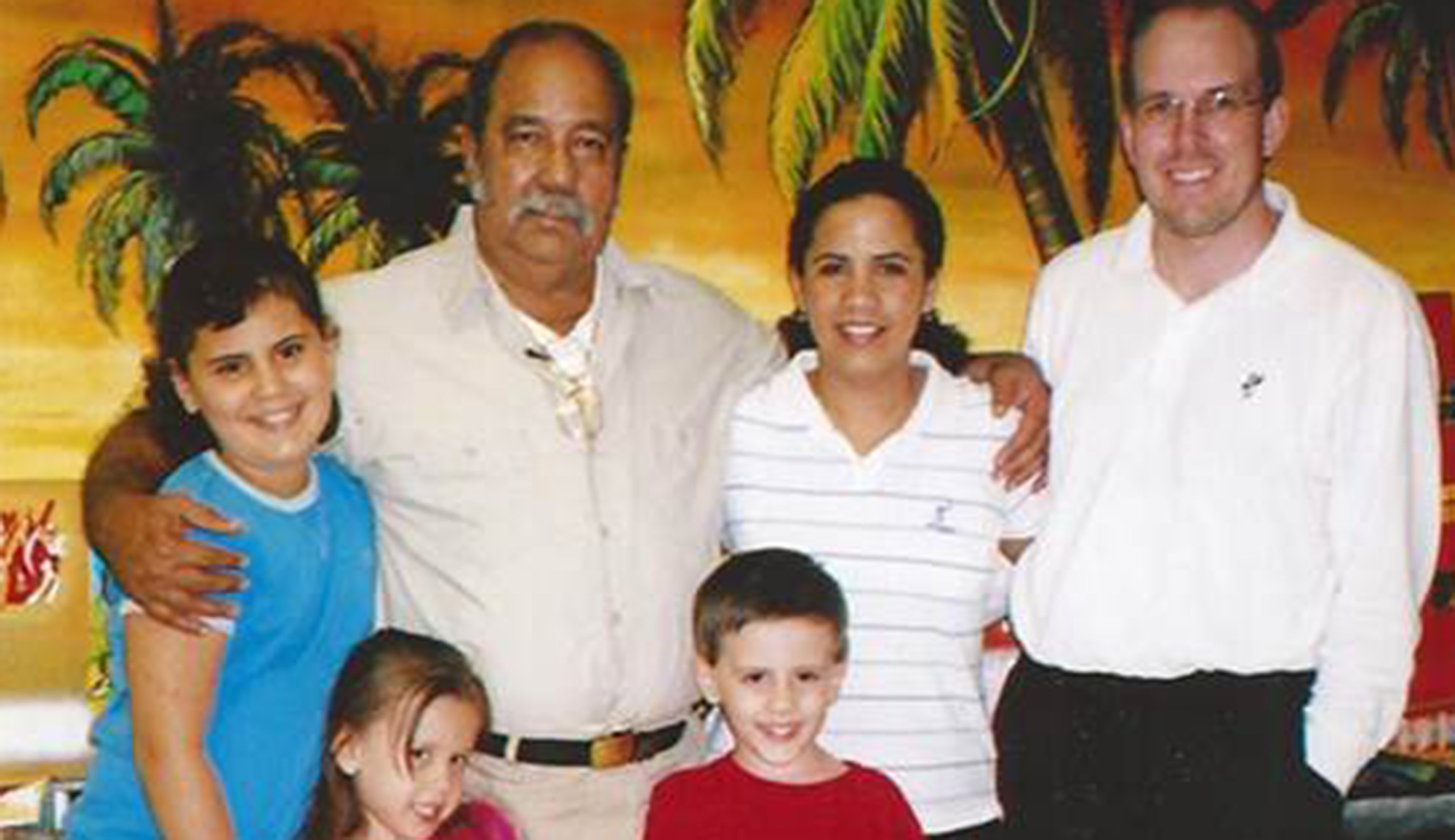

Bascaro has three adult children who intend to support him, and he plans to live temporarily with his sister if he’s allowed. He said he’s looking forward to spending time with his four-year-old great-granddaughter.

His daughter, Myra Bascaro, said he hopes for a peaceful retirement.

“If he is deported to Cuba, he will become a political prisoner in the country. My dad believes that this will not happen. We are praying that it is true,” she said.