If you had the displeasure of perusing through the social media site formerly known as Twitter over the recent Thanksgiving holiday, you’ve probably witnessed some of the least grateful people in America. Their X posts are some variation of the meme, “A factory worker used to be able to afford the middle-class lifestyle of homeownership, two cars, a dozen children, a stay-at-home wife, and annual vacations — all on a single income!”

This meme is nothing short of a historical fantasy, an economic distortion no less dishonest than the 1619 Project. For good reason, much of the online pushback has focused on the historical living standards wrought by the average household: From roughly the end of the Civil War until after World War II, the majority of Americans did not own their homes. The average family crammed into a house or apartment of fewer than 1,000 square feet, from the start of the Republic until, again, after World War II. None of this is to mention that in that halcyon decade after World War II, one in five households lacked indoor plumbing, and virtually no households had two cars.

But who funded the average American household is as significant as what the average household could afford. And the fact is that the notion of a single-income middle-class household was a historical anomaly, restricted to that World War II era and practically unheard of before that. Modern men cannot possibly blame women for taking their jobs, if only because outside of that post-World War II anomaly, the majority of American women have always worked for pay.

The Census Bureau has historically ignored the economically productive work of women, with three-quarters of the employment entries for women in the 1860 Census being literally left blank. In the past, this has meant that economists have been forced to estimate imprecise female labor force participation rates by generalizing wildly incomplete data.

After the 2019 release of 19th-century Census microdata, George Washington University economists Barry Chiswick and RaeAnn Robinson have put together the most comprehensive portrait of women’s “productive activities that enhance a family’s economic well-being, either directly or indirectly, related to a household’s economic activities beyond producing in the household for the household’s own use.” In other words, female labor force participation that was not counted by census contemporaries, but would be qualified as actual employment rather than mere homemaking by labor economists today.

Although the census reported just 15% of women aged 16 and older as participating in the labor force in 1860, Chiswick and Robinson found that when including the 36% of women who farmed, 3% who worked in the family shop, and 2% who ran the family boardinghouse, they contributed to family crafts such as tanning or pewtering. Or they did some combination of the above. When that’s factored in, the actual estimated female labor force participation rate in 1860 was 57%, or the same as it is today.

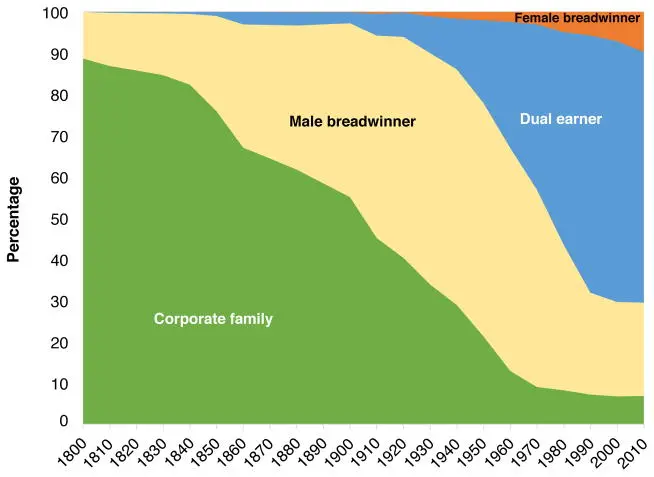

In other words, for most of American history, the economy was fueled by the corporate family. Data from a 2015 study in Demography clearly shows the male breadwinner model only comprised families from roughly 1910 through the 60s. For about 200 years of American history, women were also working for pay.

TRUMP’S REVOLUTIONARY CHILD SAVINGS ACCOUNTS AREN’T ‘PRONATALIST.’ THEY’RE SOMETHING BETTER.

Skeptics will ask, who exactly was watching the children while these historical #girlbosses were milking cows or managing the bookkeeping for the family business? The answer is, nobody. For most of American history, infants were strapped into cradleboards and toddlers into standing stools until they were old enough to tend to themselves and then begin their own foray into paid work. As late as 1925, married mothers of at least two children under the age of 5 spent barely an hour taking care of their children each day.

Today’s economy has real problems, including government spending that fuels the erosion of your paycheck. And government zoning regulations that make it illegal to build the 7 million houses consumers still demand. But the return of the multi-earner household is not one of them.