Last spring, when it was becoming increasingly clear that liberal hero Elizabeth Warren would decline a run for president, Bernie Sanders laid out the case for a left-wing candidate to challenge Hillary Clinton.

“Is Hillary Clinton, are other candidates, prepared to take on the billionaire class?” the Vermont senator said in an April interview with Bloomberg’s editors. “Based on her record, I don’t” think so, he said.

A few weeks later, Sanders, an independent who identifies as a Democratic socialist, entered the Democratic race.

On the stage during the first Democratic primary debate in October, only Sanders represented the progressive faction within the Democratic Party that had been emboldened in recent months by Warren. Sanders’ debate opponents were Clinton, Martin O’Malley, a technocratic former governor of Maryland formerly associated with the centrist Democratic Leadership Council; Lincoln Chafee, the former Rhode Island governor who joined the Democratic party only two years earlier; and Jim Webb, a former Virginia senator who served in Ronald Reagan’s administration.

The self-styled “Warren wing” of the party desperately needed a candidate on the stage and in the primary to pull the conversation their way.

Sanders has done that and more, posing a legitimate threat to Clinton. For a range of policy issues important to liberals, Sanders has shifted the field to the left. In many cases, the presence of a liberal rival has led Clinton to embrace economic policies demonstrably more liberal than positions she has staked out in the past.

“One year ago, it was almost unimaginable, by many, that top presidential candidates would be competing with each other to be bolder on issues like Wall Street reform, jailing Wall Street bankers who broke the law, expanding Social Security and debt-free college,” said Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, one of the outside groups that has pushed lawmakers to adopt populist policies.

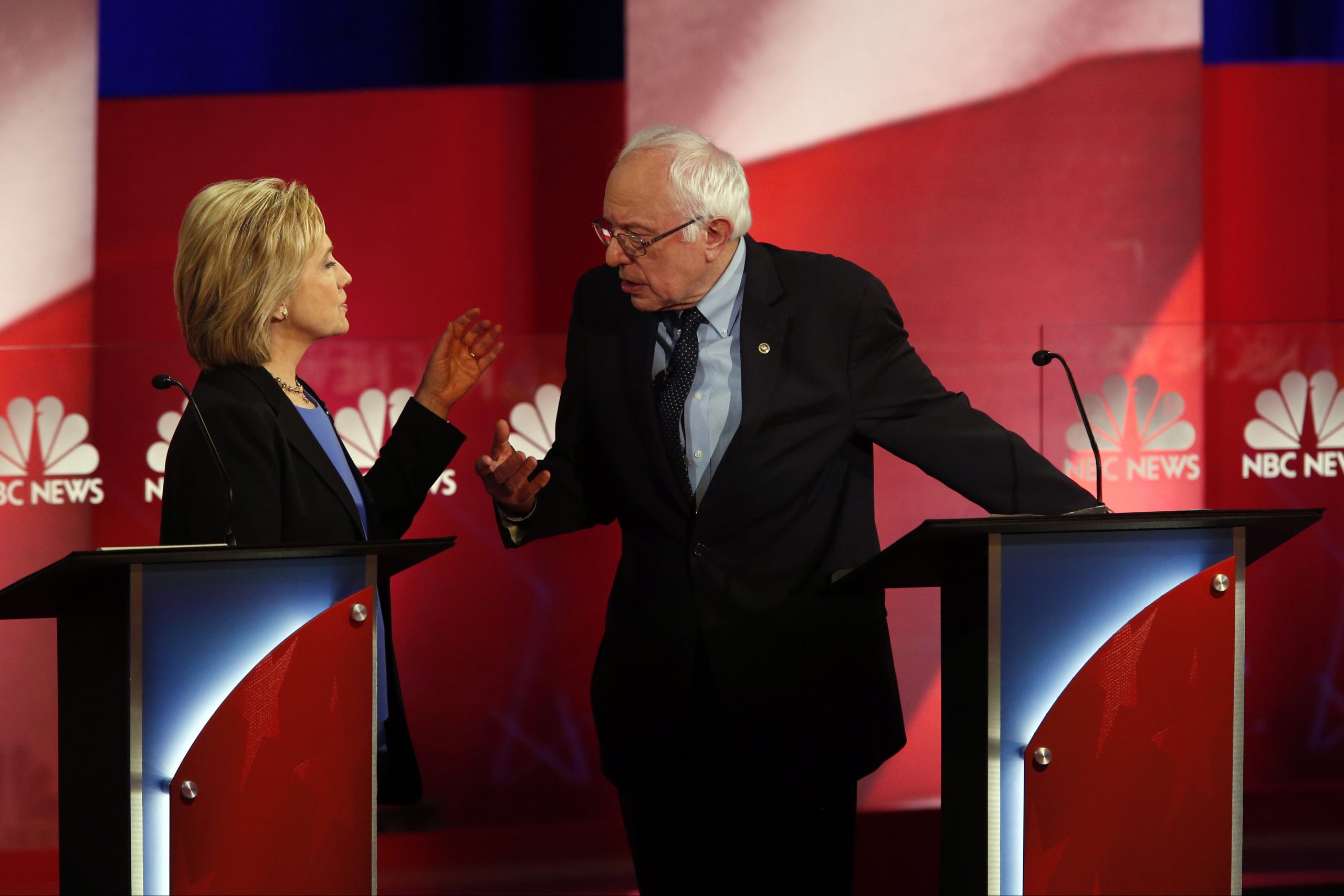

Hillary Clinton’s plan cannot convey the same populist anger that Bernie Sanders projects every time he alleges that Wall Street’s business model is fraud, or when he calls out Goldman Sachs head Lloyd Blankfein as an example of Wall Street greed. (Bloomberg Photos)

“The debate within the Democratic primary largely is not about which direction to go. It’s about how big to go and how precisely to get there,” Green said. “For progressives who have been working on a lot of these economic populism issues for a long time, it’s a perfect place to have the scope of debate.”

Wall Street

Nowhere is the shift within the Democratic Party since Clinton’s first run in 2008 more apparent than in the candidates’ stances on Wall Street.

Part of the difference is the lingering resentment over the 2008 financial crisis and bailouts of big banks. Much of it also is the influence of Warren, who, since becoming a Massachusetts senator, has led liberal revolts against Republicans and the Obama White House over Wall Street issues.

Sanders has long embraced a straightforward approach to big banks: He would break them apart. He voted in 2010 for a failed amendment to Dodd-Frank that would have broken up several megabanks. In this campaign, he’s backed a longshot scheme to have regulators break up the big banks, and endorsed legislation that would recreate and strengthen the Depression-Era Glass-Steagall separation of commercial banks, investment banks and insurers.

In October, Clinton unveiled her own financial reform plan, one that contemplated bolstering many parts of Dodd-Frank and new rules for other areas of the financial system. In certain, unlikely circumstances, she would have regulators try to break up banks. She also pledged to hold financial executives responsible for wrongdoing by prosecuting them individually rather than simply penalizing corporations. It’s a practice that has outraged some progressive Wall Street critics in financial crisis-related litigation.

Clinton’s plan cannot convey the same populist anger that Sanders projects every time he alleges that Wall Street’s business model is fraud, or when he calls out Goldman Sachs head Lloyd Blankfein as an example of Wall Street greed.

But it is a marked difference from her campaign platform in 2008.

Then, despite being aware of the subprime mortgage crisis that was unfolding around her, Clinton offered almost no ideas for reforming or re-regulating the financial sector.

In a December 2007 speech delivered at the NASDAQ exchange, Clinton pinned the blame for the mortgage crisis on Wall Street. But her prescriptions for reform were to call for a moratorium on foreclosures and a freeze on interest rates on adjustable-rate mortgages. These were stop-gap measures that do not compare to the reforms that were enacted.

A review of Clinton’s campaign statements and speeches, as well as of her debate appearances, indicates that Wall Street reform was not a priority, and that she didn’t highlight other proposals for tightening regulations or enhancing oversight. In fact, the party as a whole largely ignored the financial industry. Neither Clinton, Barack Obama nor other candidates spoke at length about reform in the debates.

In contrast, the past weeks have seen Clinton and Sanders square off over who would be tougher on Wall Street.

One additional note: Last spring, Sanders called for a $300 billion annual financial transactions tax to pay for free higher education. Clinton stopped short of that revenue-raising provision, but did call in her plan, released in the fall, for a tax on a certain form of high-frequency trading thought by some analysts to be abusive. It’s unclear from her proposal whether or how much revenue the levy would raise.

Higher education

After Democrats were rocked in the 2014 election, the Progressive Change Campaign Committee laid out a plan for debt-free college, an idea the group thought could galvanize young, indebted people into coming to the polls. The idea, which closely tracks the concept of free higher education long favored by some liberal progressives, quickly caught on among congressional Democrats.

Sanders again staked out a very aggressive form of the idea with his higher education plan, which eliminates tuition at public universities and colleges. “We should look at college today the way high school was looked at 60 years ago,” Sanders said in the December Democratic debate in New Hampshire.

Clinton’s plan would create federal incentives for states to limit tuition increases and increase funding for state schools. (AP Photo)

Clinton took on Sanders’ plan at that debate. “I don’t believe in free tuition for everybody,” she said. “I believe we should focus on middle-class families, working families and poor kids who have the ambition and the talent to go to college and get ahead.”

Clinton’s plan would create federal incentives for states to limit tuition increases and increase funding for state schools to prevent students from having to take out loans to attend.

For liberals, the debate was a measure of the success they’ve had in shaping the Democratic Party.

The exchange “really kind of articulated what Sanders is doing to the presidential debate,” said Neil Sroka, a representative for Democracy for America, one of the progressive groups that had tried to draft Warren into the race. “It’s fundamentally changing the dialogue about economic policy in this country.”

Clinton’s endorsement of debt-free college, a plan that would cost an estimated $350 billion over 10 years, would have been shocking to her 2008 campaign. Then, her plan for college affordability was to double the Hope tax credit, at a cost to the Treasury of around $8 billion a year.

Taxes

Sanders’ ambitious plans come with similarly aggressive policies for raising revenues to pay for them. Altogether, he has penciled in nearly $20 trillion in tax increases over the next 10 years, or roughly a 50 percent increase in total tax revenues.

Those tax hikes, including ones that would affect middle class families, are a political liability, one that Clinton has tried to exploit during the primary.

Nevertheless, she has shifted her own stance on taxes radically in recent years. This cycle, she rolled out a raft of ideas for raising taxes on high earners and preventing them from gaming the tax system. The plan features a four percentage point surtax on families earning over $5 million, and tax changes to limit tax breaks that wealthy families can claim.

It’s a marked change from 2008, when she and Obama campaigned on simply reversing the Bush tax cuts that accrued to the high earners.

Clinton’s own plan, a complicated scheme intended to prevent short-sighted thinking at companies, would raise the rate to 47.4 percent for some capital gains. (AP Photo)

“It’s just really important to underscore here that we will go back to the tax rates we had before George Bush became president,” she told the audience in a January 2008 primary debate in California.

Then, she also indicated she would raise only the top tax rate on capital gains to 20 percent. Today, it is 23.8 percent, and Sanders has proposed a highest ever rate of 60 percent. Clinton’s own plan, a complicated scheme intended to prevent short-sighted thinking at companies, would raise the rate to 47.4 percent for some capital gains, more than double the rate she favored in 2008.

Social security

There is one tax hike in particular, however, that Clinton has stopped short of endorsing: an increase in taxes on Social Security.

The Democratic Party has shifted on Social Security policy significantly in the past two years. President Obama, for several years, made congressional Republicans an opening bid for deficit reduction that included changing the way benefits are calculated that would have reduced payments.

The deal was never struck, and the offer has since come off the table, but liberals felt burned by the possibility that one of the most popular government programs was at risk for cuts.

In the summer before the midterm elections of 2014, Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown, one of the most liberal members of Congress, called for expanding, not cutting, Social Security benefits. Warren picked up on the call to expand Social Security, making it a benchmark for progressivism. In March last year, she offered a symbolic amendment to the budget resolution expressing support for expanding Social Security benefits. All but two Democrats voted in favor.

The flip side to spending more through Social Security is that the benefits must be financed. Sanders would do so by instituting Social Security payroll taxes on incomes over $250,000. Currently, the tax is capped on the first $118,500.

Clinton’s stance on Social Security is the “one unchecked box in our minds,” Green said. “What she has not yet said is that she will never cut benefits.”

Nor has she committed to paying for expanded benefits.

In recent weeks, however, she has crept closer to the pro-Social Security position favored by liberals.

In a January campaign event in Iowa, she suggested that she would consider applying Social Security taxes to some investment income or to more labor income. She also has mentioned several times increasing benefits for low-income earners, widows and caretakers.

Although she hasn’t committed to specific tax increases or added benefits, Clinton’s statements represent progress in the eyes of liberals. In 2008, she objected to raising the cap on taxable income, and backed the idea of a commission for shoring up Social Security’s finances, a prospect viewed warily by liberals fearful of a deal to cut benefits.

Minimum wage

The most straightforward benchmark progressives have set for Democratic candidates is the minimum wage: a single number that can serve as a gauge of liberalism.

Democrats have been in a bidding war over the minimum wage since Obama called for raising the federal hourly wage floor from $7.25 to $9 in the 2013 State of the Union.

Sanders matched the highest bid offered by any high-level Democrat in July, introducing legislation to raise the minimum wage to $15 by 2020.

In November, Clinton joined the majority of Senate Democrats in backing a $12 minimum wage, although she has also said that she favors state and local measures to go even further.

That represents a slightly more aggressive stance than she has embraced, reflecting the organized efforts by unions and liberal groups to pressure lawmakers for higher minimum wages throughout the country.

In November, Clinton joined the majority of Senate Democrats in backing a $12 minimum wage, although she has also said that she favors state and local measures to go even further. (AP Photo)

In the 2008 campaign, Clinton endorsed raising the minimum wage to $9.50 by 2011. Accounting for inflation since then, that translates to about a $10.50 minimum wage today, or roughly $11.50 by 2020, assuming 2 percent annual inflation.

Trade

The Obama administration’s second-term push for a Pacific-nation trade deal has split Democrats.

Sanders has opposed it. Throughout his congressional career, Sanders has consistently been on the liberal side over trade, arguing and voting against numerous trade deals as anti-middle class legislation that would aggravate inequality.

Sanders delivered a representative speech on trade during a 2007 debate over a proposed trade deal with Peru, the first such major deal of Sanders’ Senate tenure.

“The untold story of the economy in the United States is that the middle class is shrinking, poverty is increasing and the gap between the rich and the poor is growing much wider,” Sanders said in a floor speech then. “I am not going to stand here and tell you trade is the only reason the middle class is shrinking, but I am going to tell you it is a major reason, and it is an issue we have to deal with.”

Only 16 Democrats voted against the bill, while 29 voted for it. Clinton missed the vote while on the campaign trail, but said that she would have voted “yea.” For her absence, she was criticized by the media.

As secretary of state, Clinton supported and helped build the Pacific trade deal, which is known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and has yet to be approved by Congress. Throughout her tenure, she offered strong and repeated support for the deal, at one point calling it the “gold standard” of trade deals.

Throughout his congressional career, Sanders has consistently been on the liberal side over trade, arguing and voting against numerous trade deals as anti-middle class legislation that would aggravate inequality. (AP Photo)

In October, however, Clinton reversed her support for the deal. With the text of the 12-nation deal available, she said that “the bar here is very high and, based on what I have seen, I don’t believe this agreement has met it.”

In a debate that month, she explained that “it was just finally negotiated last week, and in looking at it, it didn’t meet my standards.”

A closer look at Clinton’s record reveals that she hasn’t reliably favored or opposed recent trade deals. She backed her husband’s negotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement in the 1990s, but later, during her Senate tenure, argued that the deal hadn’t lived up to its promises, and voted against the Central America Free Trade Agreement.

Sanders, on the other hand, voted against all of them, as a matter of opposing greater income inequality.

Inequality, in turn, is the key to understanding liberals’ shift over the years, Sroka said.

“That’s the big theme that underlies many of these specific debates,” he explained. “Part of the reason you see Sanders surging is because people are hungering for that fundamental altering of the status quo.”