LOS ANGELES, California — Scandal-tinged members of Congress usually quietly disappear from public life. Now, two House members who drew waves of unflattering headlines are trying for comebacks, at lower political levels.

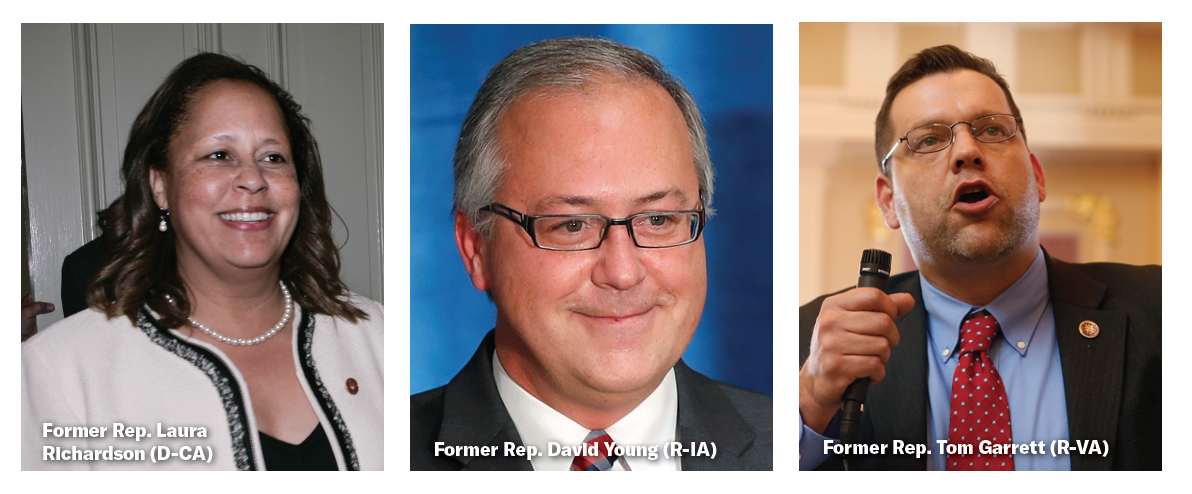

Former California Democratic Rep. Laura Richardson and former Virginia Republican Rep. Tom Garrett, after years out of the political spotlight, are running for seats in their respective state legislatures. Richardson faces a tougher road back, while Garrett is likely to waltz into office in Virginia’s November 2023 legislative elections.

ELECTION OF GOVERNORS: GUBERNATORIAL RECORDS OF SIX 2024 REPUBLICAN PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES

Richardson was once a rising star in Southern California politics. A six-year member of the Long Beach City Council, Richardson was less than a year into her first term in the state Assembly when she won a House special election for a district covering inland Los Angeles and inland Long Beach, and the smaller cities of Carson, Compton, and Signal Hill.

Richardson was secure politically until redistricting led to her 2012 faceoff with fellow Democratic incumbent Janice Hahn. Richardson spent that campaign dealing with news reports alleging she had mistreated her staff, to the point that one disabled veteran in Richardson’s office wrote in her resignation letter that she would “rather be at war in Afghanistan” than continue to work for the congresswoman.

The House in August 2012 reprimanded Richardson after the Ethics Committee found she had pressured her congressional staff to do campaign work and demonstrated a “pattern of omission and deception” regarding its investigation. She went on to lose reelection to Hahn that November 60% to 40% in the state’s first use of its “top two” election system, in which members of the same party face each other in the general election because they have finished first and second in the primary.

Richardson has largely kept a low profile since then. But she recently launched a comeback campaign for the state Senate. The district Richardson seeks to represent includes much of the same, or nearby, territory as her one-time congressional seat.

She will compete in the March 5, 2024, top-two primary to succeed a state senator being forced from office by term limits. Richardson faces a crowded Democratic primary field in a race whose first round of voting is still nearly nine months away.

Across the country, Tom Garrett has a clearer path back to political office, at a lower level than the one he left. Garrett spent a single, chaotic two-year term in Congress from 2017-19 representing a southwestern Virginia district after five years in the state Senate.

But Garrett abruptly ended his 2018 reelection campaign after disclosing he was focusing on his fight with alcoholism. And while many would commend Garrett’s decision to put a hold on his political career to deal with addiction, he faced a wave of unflattering news headlines on other fronts.

The House Ethics Committee issued a lengthy report on Garrett’s final day in office, determining that he had violated House rules by directing his staff to run personal errands for him. Employees of the then-congressman’s office also told the ethics panel that his wife “would berate staff, often using profanity and other harsh language, for failing to prioritize her needs over their regular official duties.” The report additionally accused the Garretts of deliberately dragging their feet during the investigation so that they could run out the clock and avoid censure before the congressman’s term expired.

After leaving Washington, Garrett, too, kept a relatively low profile. Yet now he’s likely to return to his old political stomping ground in Richmond. He recently won a party nomination convention for a safely Republican state House of Delegates seat around Appomattox.

Joining the club of ex-House members in office elsewhere

Richardson and Garrett are hardly the first former House members to seek office further down the political food chain.

That’s the case in Iowa with Republican state Rep. David Young. A Capitol Hill staple for years, the Van Meter, Iowa, native worked his way up to chief of staff for the late Kentucky Republican Sen. Jim Bunning. In 2006, Young became chief of staff for his home state Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley.

Fulfilling the dreams of many political staffers to hold office themselves, Young in 2014 won an open western Iowa House seat. But Young lost in the 2018 Democratic wave and fell short in a 2020 comeback bid. Then, in 2022, Young won a state House seat representing the western suburbs of Des Moines.

There was a much greater political time lag in Texas for Democratic state Rep. John Bryant before his return gig. In 1974, Bryant, then a 27-year-old lawyer, won a special election for a Houston-area state House seat. In 1982, Bryant was elected to Congress at a time when Democrats still dominated Texas politics but the Lone Star State was becoming more politically competitive for Republicans.

Bryant in 1996 gave up his House seat to run for the Senate, losing in the Democratic primary as Texas was moving firmly into the GOP column. Bryant largely stayed out of politics for the next nearly quarter century.

Yet in 2021, Bryant filed to run for state representative in Texas’s 114th District, covering part of the city of Dallas. Bryant cited former President Donald Trump as a motivation.

“I am so alarmed at the continued extremes to which the Trump forces have gone in trying to take our country over and now this has arrived in Texas. I want to get off the sidelines and get back into the fight.” Bryant won the primary in May 2022, and the general election in November of that year.

Out of politics — and loving it

Some defeated pols are happy to leave politics entirely. That’s what former Mississippi Democratic Rep. Travis Childers seems to have done, focusing instead on real estate.

Childers was elected to the House in a 2008 special election, then was defeated in 2010 by Republican Alan Nunnelee. He was the 2014 Democratic Senate nominee in Mississippi but lost badly.

He’s since returned to his professional roots. While a student at the University of Mississippi, Childers became a real estate salesperson. Based in the northeast Mississippi city of Booneville, Childers went on to be elected Prentiss County Chancery Clerk, his position upon election to Congress.

Now gone from Washington for more than a dozen years, he runs Travis W. Childers Realty & Associates, Inc. His professional website lacks any reference to his time in Congress. It’s a stark contrast from other relatively short-time House members who have tried to parlay their public service into lucrative lobbying and consulting gigs.

That was never the intention of former Colorado Republican Rep. Bob Schaffer, a House member representing the state’s conservative eastern portion from 1997 to 2003.

Schaffer abided by self-imposed term limits in leaving office and took a bit of a circuitous route to his current role as headmaster at Liberty Common School in Fort Collins, Colorado, north of Denver.

After Congress, two years into then-President George W. Bush’s administration, Schaffer worked for a time at an oil-and-gas company, he recalled in an interview with the Washington Examiner. But education was a passion, and Schaffer, as a private citizen, went on to head two nonprofit organizations in the school reform movement. He also orchestrated the passage of a school voucher system in Colorado, which was subsequently thrown out by the state Supreme Court.

Schaffer was appointed to the state Board of Education for a year and then won a full, six-year term. Two years in, Schaffer ran for the Senate, winning the Republican nomination, but losing in November 2008.

Since his state Board of Education term ended, Schaffer has been busy in various administrative roles at Liberty Common High School, a tuition-free, charter-public school. It serves students from K-12, spanning three campuses.

“We are dedicated to the Core Knowledge curriculum, and college-preparatory instruction,” according to the school’s website. “Students at Liberty Common School are exposed to classically-oriented education, focusing on literacy and Great Books. They are also taught foundation stones of character education in the elementary, which scale up to ‘capstone virtues’ of our junior-high and high-school.”

It’s a fulfilling professional role for Schaffer.

“It’s unlikely there are many Americans who have as many varied experiences in education as I have,” he said. But his congressional days — and nine years as a state senator in Colorado before that — aren’t much a part of his professional persona.

“Kids don’t call me ‘congressman.’ At most, the teachers in their government classes will occasionally say, ‘Mr. Schaffer used to serve there.’”

Not that Schaffer doesn’t occasionally muse about being far away from the action.

“I miss being involved in some of the education policy debates,” Schaffer said. Back then, Schaffer was among a small group of House Republicans who in 2002 opposed the No Child Left Behind Act, one of the Bush administration’s signature domestic achievements.

Schaffer and conservative colleagues helped negotiate the initial version of the school reform efforts but became dismayed when more federal spending provisions were added in.

“It was no longer an aggressive tool for school choice. It was no longer an aggressive strategy for sending block grants back to the state for education,” he recalled. “The U.S. Constitution spells out the authority in Congress. Nowhere does public education appear of being in the jurisdiction of the federal government.”

Also, Russia’s continued aggression against its southwest neighbor harkens back to one of Schaffer’s focuses in the House.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“I was co-chair of the Congressional Ukrainian Caucus. I am in tune and about as knowledgeable about the U.S. interest in Eastern Europe as I ever was when in Congress,” said Schaffer, whose mother’s family is of Ukrainian descent.

Still, education makes for a contented professional life, Schaffer said. So, unlike former Reps. Richardson and Garrett, don’t expect to see him clamoring to return to public office.