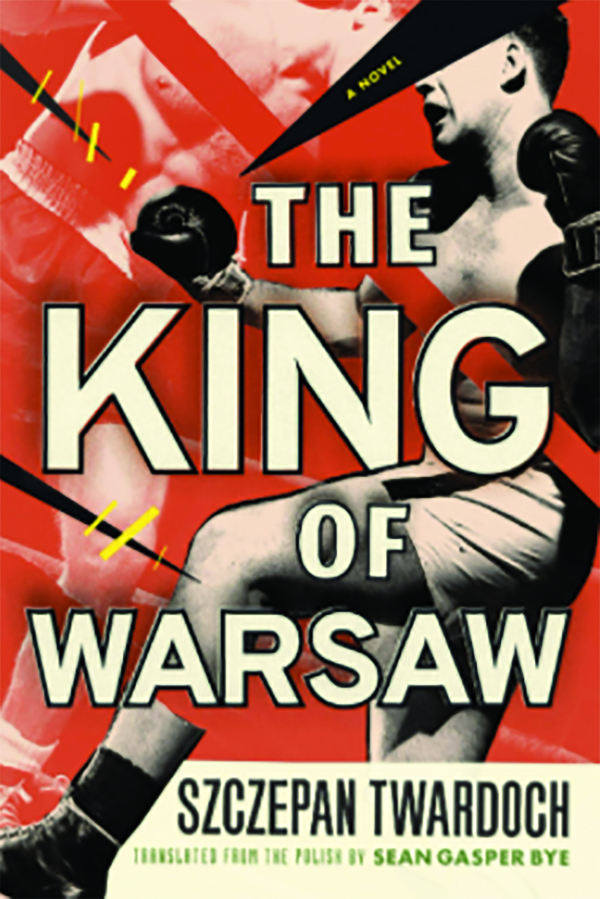

The King of Warsaw is the Polish version of Goodfellas. The first of Szczepan Twardoch’s novels to be translated into English, it follows a young man as he enters the world of Warsaw gangsters. It’s clear why this plot-heavy tale of Poland in the 1930s was a bestseller in Europe: It’s packed with villainous hit men, street brawls with Nazis, whores with hearts of gold, and political coups. Though it is told in the looming shadow of World War II, the story focuses on Warsaw’s lowlifes. If The King of Warsaw sometimes feels a bit too familiar, it is still an entertaining pulp read for summer.

The novel’s protagonist is Jakub Szapiro, a prize-fighting boxer and lead enforcer for the Jewish mafia in Warsaw. Jakub’s tale is narrated by Mojzesz Bernsztajn, an Orthodox Jewish teenager. Mojzesz narrates the novel retrospectively, and the book cuts between the ‘30s and present-day Israel, where he is a retired general. This narrative frame brings a dream-like quality to the Warsaw portions. At the outset of the book, Jakub drags Mojzesz’s father out of his apartment and murders him for missing payments. After chopping the body up into pieces, Jakub becomes riddled by guilt and takes Mojzesz under his wing as an adopted son. Jakub carries out various missions for his gang, which is the criminal element of the Socialist Worker’s party, and Mojzesz catalogs a phenomenon that used to be rare in America: politics via gang warfare. As the political tensions rise and the gang violence escalates, Jakub begins to question whether he should leave Poland with the Zionists.

The King of Warsaw paints an elaborate portrait of Warsaw’s gangland. The wide-ranging cast of characters carries the story — the reader is introduced to crooked sports writers, tempestuous brothel owners, and even a schizophrenic hit man with a birth defect that makes it appear as if he has a second face on the back of his head. Almost every character is given a detailed backstory placing them within the larger web of Warsaw gangsters. At times, this noir romp feels a little too influenced by its genre antecedents. The femme fatales plotting revenge feel familiar, and bodies are always being stuffed into trunks. The dialogue can be a bit campy, as when Jakub confronts a group of nationalist writers and shouts, “Shut your face intelligentsia scum.” But if the plot elements feel familiar, the book’s Jewish mobster setting makes it feel unique.

Unfortunately, The King of Warsaw stumbles with its narrative choice. As characters are introduced, Mojzesz recounts their backstories, and this world-building often undermines the dramatic tension of the actual scene. For example, the story builds toward a huge battle with the nationalist street gang. As the protagonists flee the carnage of the battle, one of the main characters is shot in the arm. Suddenly, the story leaves the battle to recount the two other times this man had been shot.

Issues like this are compounded by the use of an unreliable narrator. Mojzesz is not confident that his memories of the ‘30s are accurate, and he often discusses the haziness of memory. The reader is constantly given information only to have the narrator second-guess its veracity. Sometimes, this succeeds in creating a dream-like atmosphere, but more often, it creates a choppy reading experience, drawing readers out of the scene and asking them to doubt the sentence they just read. As the novel progresses, the scenes of Mojzesz in Israel become hazier, revealing an unraveling mind. This leads to a twist toward the end of the book, and the novel does a great job of foreshadowing this reveal from the first page. Yet the twist also undermines everything that preceded it, radically changing the nature of the first two-thirds of the book and causing entire plotlines to disappear.

Despite these stumbles, The King of Warsaw’s exploration of interwar European politics elevates it above mere pulp. America’s political imagination has only two reference points: Berlin 1933 and Selma 1965. Our commentariat is always warning of imminent fascism, and our corporate overlords are always using the Civil Rights movement as advertising. The King of Warsaw deals with the rise of fascism story we’re all familiar with, yet its Polish setting is different enough to add clarity. In the novel, nationalists and socialists are not so much ideological positions as they are tribal identities. There is no ideological coherence to the Jewish mobsters who terrorize and torture members of their own community but also defend them against nationalist gangs. And the gang violence is tolerated by political leaders because some of the gang members have personal ties to the political establishment.

The politics of 1930s Europe is now in America. There is no ideological coherence to our riots, and anyone who tells us that teenagers looted stores in a grand political gesture was never a teenager. Similarly, the more militant rioters have close ties to political power. In New York City, Ivy League-educated lawyers lobbed Molotov cocktails at the police, and the mayor’s daughter was arrested as part of a mob throwing bottles at the New York Police Department. Corporate America sent out ceaseless marketing emails in support of demonstrations while rioters beat up journalists and small-business owners.

The King of Warsaw has significant stumbles, but it is an entertaining pulp novel that is strangely relevant in our new politics-by-mob America. It reminds us how elites rile up mob violence to support their own agenda. Nothing good follows.

James McElroy is a novelist and essayist based in New York.