Last Tuesday, Texas senator Ted Cruz won re-election in Texas, but he beat Beto O’Rourke by only 2.6 percentage points. That’s an uncomfortably close margin for Texas Republicans, who are used to winning by double digits even in unfavorable national environments. And that margin (along with the high turnout) has led some to ask if 2018 is the shape of things to come – that is, if the results represent a shift in Texas’s baseline partisanship.

I don’t think this is an easy nut to crack. Evaluating this race means weighting 1) the specific value-over-replacement of Beto O’Rourke vs. other Democratic candidates, 2) the generally pro-Democratic national environment in 2018, 3) how the Trump presidency is moving Texas Republicans as it wears on, and 4) how Texas’s turnout levels are changing over time. Reasonable people could rate these factors differently and come up with different reads on the underlying partisanship of the state.

So I’m going to do something a little unusual. I’m going to interpret the data in a really rosy way for Democrats and a really rosy way for Republicans. Before I get started: I don’t fully buy either of these interpretations, and you shouldn’t read either as my final analysis. The goal is to get a range of possible interpretations by imitating the arguments of a decent partisan, and use that range to talk about where Texas is and where it might be going in 2020 and beyond.

An Optimistic Argument for Democrats: Beto Isn’t Special

One good interpretation of these results for Democrats is, maybe counterintuitively, that O’Rourke wasn’t that special. They might argue that Texas has always been heading in this direction, O’Rourke was an inevitable next step and that Democrats will be able to win in Texas soon even if he’s not running.

The basic evidence for this view is that Texas hasn’t been voting the way that it “should” for quite some time.

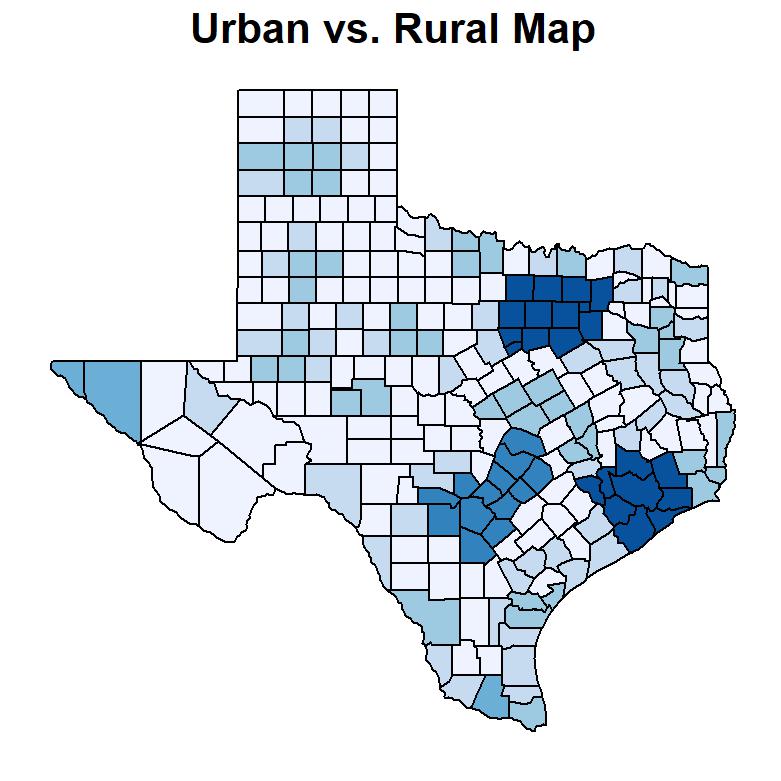

We can start to get a sense of why by looking at this map:

This map shows the “CBSA Areas” (defined here) in the state of Texas. Basically the darker-colored counties are part of larger metro areas and the lighter parts are either towns or rural areas.

This map is a direct rebuttal to the cowboys-and-tumbleweed stereotypes about Texas. The state has four major cities (Dallas, Houston, Austin, San Antonio), some smaller cities/towns and a lot of sparsely populated land. In both 2016 and 2018, two thirds of the major party votes in the top-of-the-ticket races (president and Senate respectively) were cast in these three major cities.

In other words, Texas is firmly on the urban side of the urban/rural split. That’s good for Democrats. Their national coalition has become more reliant on big cities over the last couple of decades. For much of the 1990s and 2000s those urban/suburban gains didn’t help Texas Democrats (Republicans actually made gains in Texas in that interval). But in 2016, the state moved left (only voting for Trump by nine points) and Democrats could argue that 2018 at least solidified on those gains if not built on them.

Democrats might also argue that the turnout might be better for them now than it has been in the past. Turnout in Texas was high compared to recent levels (just compare 2018 to 2014 and 2010), and Texas Democrats tend to see better results when polls get less restrictive (i.e. polls of all adults are often better for Democrats than those of likely voters). So if Democrats can increase turnout permanently, they may stand a better chance of winning.

Moreover, O’Rourke might have left votes on the table. This map, generated by DDHQ’s excellent cartographer, J. Miles Colman, compares the raw votes that Clinton and O’Rourke got in each county.

In #TXSen this year, Beto O’Rourke (blue) got 148K more votes than Hillary Clinton (red). Something of a function of population, but his best gain was in Travis County (Austin), where he got 49K more votes. His biggest drop was 14.5K votes in Hidalgo County (McAllen). #txlege pic.twitter.com/oubR2fndy6

— J. Miles Coleman (@JMilesColeman) November 11, 2018

Some of the reddest areas are in Southwest Texas, which happens to be one of the more heavily Hispanic areas of the state. It’s tough to infer too much from county results (there are ecological issues, and we’ll want to wait for voter file, precinct and other data before making too strong of inferences about turnout and vote share among groups) but Hispanic turnout in Texas is usually low and Democrats could argue that O’Rourke hasn’t necessarily maxed out Democratic potential in the state.

If you grant all these arguments, then you could get to a place where you believe that Texas is only somewhat red and that non-landslide but still pretty Democratic-friendly conditions could put Texas in play in 2020.

An Optimistic Argument for Republicans: There Are Still a Lot of Republicans in Texas

Republican optimists would probably first note that they won in Texas despite many forces pushing against them. Cruz faced O’Rourke (a great fundraiser who got constant adoring media coverage) in a year when Democrats consistently led in the generic ballot by mid-to-high single digits. If you were to assume that O’Rourke’s advantages as a candidate didn’t quite cancel out Cruz’s advantages as an incumbent (reasonable people can argue about the exact bonus that comes from candidate strength) and you add seven points to Cruz’s margin (because Democrats won the House popular vote by seven) you would guess that Republicans have a high single digit baseline advantage (in terms of margin) in Texas.

You could push that baseline further to the right by either arguing that O’Rourke is an even better candidate than this analysis suggests or by including other past results. (e.g. the 2012 results were much better for Republicans and Republicans tended to do better than Cruz in key statewide races prior to 2018). There’s all sorts of adjustments you could make to this number that would put the GOP baseline advatange (again in terms of margin) into the double digits. This still represents a GOP decline since its high point in the 2000s, but it would basically put the state out of Democratic reach in all but truly catastrophic circumstances.

Other races also suggest that there’s still Republican DNA in some new Clinton and O’Rourke converts. Greg Abbott, the Republican governor, won re-election by 13 points, and George P. Bush (Jeb Bush’s son) won by 10 points in 2018. As recently as 2012, Mitt Romney won the state by 16 points despite losing the popular vote by four points. It’s not crazy to think that some of these voters aren’t solid Democrats at this point: They’re swing voters who have seen Trump (who didn’t appeal to them) in one election and a strongly Democratic environment (basically created by Trump’s low approval ratings) in the next election. And the GOP could win them back.

Simply put, Republicans could argue that Texas is still a red state at its core and that many Democratic converts are just borrowed Republicans. These borrowed Republicans have cast their ballot for the GOP in the past, and some of them voted for other Republicans while pulling the lever for O’Rourke. Republicans should be able to regain some of these voters in a more Republican-friendly environment (and it’s hard to get more Democratically-friendly than 2018, when they took the House), and if they nominate candidates who are better suited to the state than Trump or Cruz, they’ll be able to keep it off the map.

Finding the Truth and Biting the Bullet

I don’t think either of these arguments are right. They’re not supposed to be. They’re my efforts to get inside the head of a honest, reasonable partisan who (maybe unconsciously) cherry picks evidence to make the best case for their side. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle of these narratives—that is, Republicans probably have something around a medium-to-high single digit baseline advantage in Texas for the time being (I may revise that when all the data on this election is out), with neither party fated to dominate the state (more on that here).

But both parties should be prepared for the worst.

Democrats need to be prepared for another Lucy-and-the-football scenario, where Texas is light red enough to attract Democratic attention and effort but not purple enough for them to win. Moreover, they should be aware that winning Texas isn’t equivalent to winning the future—even if their effort pays off the GOP loses the state, Democrats might get hit hard somewhere else. American politics is fundamentally competitive, and people are generally prone to chasing shiny objects that seem to promise certainty victory

Republicans also need to be prepared for the possibility that Democrats are right and that Texas will be a swing state soon. In that case, Republicans might agree to bite the bullet, let Texas go and focus elsewhere. Texas currently has 38 electoral votes—losing it would be a big deal, but the GOP could theoretically make up for it. Ohio, which has been moving right recently, has 18 electoral votes. Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, Iowa and Maine together have 66 electoral votes. Republicans probably won’t consolidate all or even most of them any time soon, but taking over Ohio plus one or two of these other states would go a long way toward making up for the loss of the Lone Star State.

Correction, Nov. 14, 5:26 p.m.: This article initially left off San Antonio in its list of major Texas cities.