A new plan to undertake the largest infrastructure project in world history would build a 1,945-mile “energy park” that would pay for itself, deploy sophisticated security to the sometimes dangerous area and turn a largely deserted area into an economic engine.

The plan just released would also build on the cooperative relations between Washington and Mexico City to have both countries build the energy wall.

“Just like the transcontinental railroad transformed the United States in the 19th century, or the Interstate system transformed the 20th century, this would be a national infrastructure project for the 21st century,” said Luciano Castillo, Purdue University’s Kenninger Professor of Renewable Energy and Power Systems.

He heads the effort authored by 28 engineers and scientists, several of whom are members of the National Academy of Engineering. The school, led by Purdue President Mitch Daniels, a former White House budget director, is running the project.

“It would do for the southwest what the Tennessee Valley Authority has done for the southeast over the last several decades,” said Castillo.

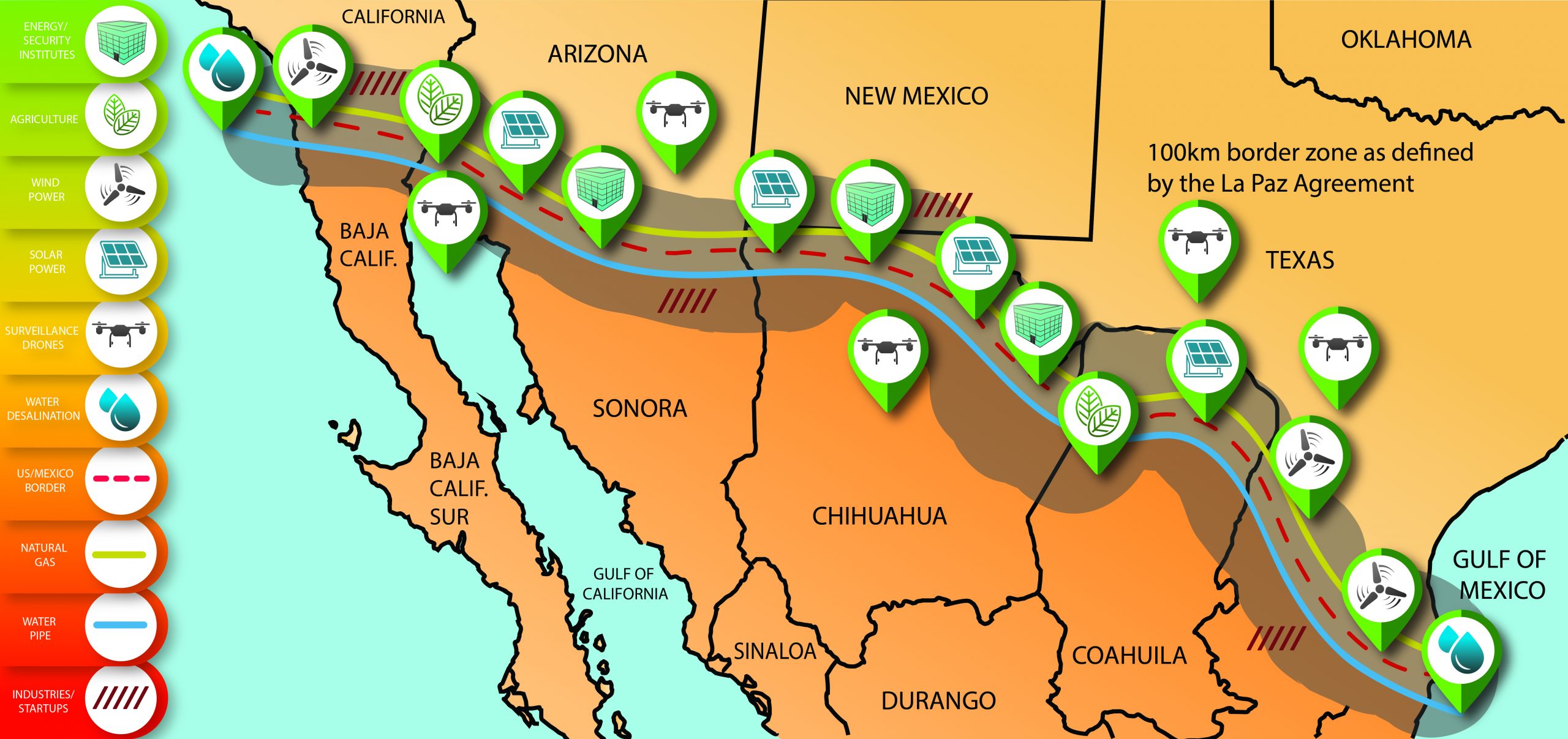

Essentially, the plan would string a train of energy panels, wind turbines, national gas pipelines along the border bookended by desalination plants, creating what the experts said would be a highly protected energy industrial park.

And because the facilities need to be protected, it would bring in tight security.

Along with that, it would be an “economic driver, both in the construction of the facilities themselves and in the businesses that would be attracted to the region by cheap electricity,” said the experts.

What’s more, it could get an easy OK from President Trump who in private meetings has talked up such a plan and its potential for “beautiful structures.”

In the plan is a blueprint of the energy wall that includes areas where solar, wind and other projects would be installed.

“At first blush the idea seems too big, too aggressive, but consider the Roman aqueducts or the transcontinental railroads — enormous undertakings that gave enormous benefits. The cost of providing basic, essential infrastructure to the border lands is tiny compared to the opportunities it creates,” said Ronald Adrian, Regents’ professor at Arizona State University and a member of the National Academy of Engineering.

“I view this project as a means of creating wealth by turning unused land of little value along the border into valuable land that has power, water access and ultimately agriculture, industry, jobs, workers and communities. With only a wall, you still have unused land of little value,” he added.

The project is also very green with its focus on solar. It also calls desalination plants on each border to pump water into the arid border area.

“Once you have water, you can have agriculture and manufacturing at levels this region has not seen before,” said Castillo. “Without this, over the next few decades the American Southwest is going to begin running out of water, and then you’re going to see another border crisis — but this one will be at the Canadian border where people will be rushing across to find water,” he added.

Martin Wosnik, director of the Center for Ocean Renewable Energy at the University of New Hampshire, also said he plan would help cut illegal immigration.

“The most effective way to stem migration, including illegal immigration, to the U.S. over the long term is to create local opportunities in the countries that people are leaving. This project provides such opportunities for the U.S.-Mexico border region,” he said.