Former President Richard Nixon had a widely influential role on former President Ronald Reagan and his key staff, and even dreamed up one of the Gipper’s most famous practices — the weekly radio address — according to a treasure trove of post-presidential papers in the Nixon library.

Author Kasey S. Pipes, the first given access to the documents by the Nixon family, found that he also helped to shape Reagan’s foreign policy and outreach to then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, and even had a role in the Star Wars missile defense project.

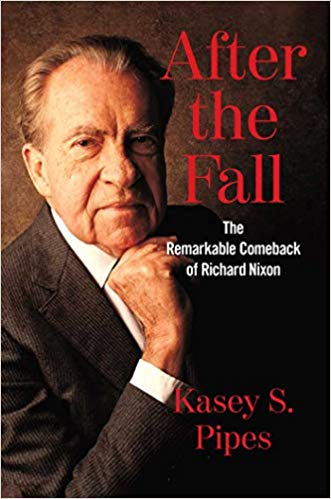

“Nixon’s private papers reveal that he continued to be a powerful influence on the Reagan White House,” Pipes wrote in his upcoming book about Nixon, After the Fall, The Remarkable Comeback of Richard Nixon, the first to fully cover Nixon’s post-presidency and bid to revive his image permanently stained by his resignation over Watergate.

Pipes built his new book around those private papers controlled by Nixon’s daughters after he was given exclusive access to them.

“Those papers revealed a man who was singed by the fire of Watergate, yes. But Nixon ultimately was strengthened by a lifetime in the fire. He was determined to make the most of the time left to him on this earth,” he wrote.

After the Fall provides some new details on the Nixon post-presidency, including:

- His support for Reagan’s pardoning of former FBI official Mark Felt, convicted of violating the civil rights of the militant Weather Underground group, and who the Washington Post later revealed was it’s “deep throat” source in Watergate coverage that led on Nixon’s resignation.

- A suggestion that Reagan dump Vice President George H.W. Bush in the 1984 reelection campaign.

- Praise for Donald Trump and prediction he would make a good elected leader.

- His desire to get more visitors to his public library.

- His strategy to avoid admitting guilt in the Watergate affair during the famous taped interviews with TV’s David Frost.

In an interview, Pipes, a former aide to Karl Rove in the George W. Bush White House, said that the papers he reviewed showed a different Nixon in the post-presidency, one eager for redemption yet “self-reflective” and even “empathetic.”

The papers related to Reagan presidency get special attention in the book in part because Reagan was president for nearly half of Nixon’s life after he resigned in 1974. He died in 1994.

A foreign policy expert who opened relations with China as president, Nixon played a role in Reagan’s successful bid to break up the Soviet Union and other foreign policy issues, and was an adviser to Reagan national security adviser Bud McFarlane, even counseling him after McFarlane attempted suicide.

Nixon’s outreach to Reagan started during the 1980 election, when the former California governor considered rejecting debating then President Jimmy Carter. “He personally lobbied for a debate,” wrote Pipes, citing a memo to Reagan’s campaign staff.

Newly revealed was Nixon’s advice on the weekly radio address, a staple for every president since — except for Trump.

Wowed by Reagan’s speaking ability, Nixon urged Reagan’s top aide Mike Deaver to put him on the radio. “You will recall the conversation we had in San Clemente several years ago about the use of radio. Why not exploit the president’s unique ability in using this medium,” wrote Nixon.

He suggested “weekly 10-minute radio talk on Sundays” to let the president “dominate the Monday papers” and bypass the White House press corps. Reagan agreed, but did them on Saturday’s to influence the Sunday talk shows and Monday papers. He gave 331 radio addresses.

And while rarely described as an inspirational president who willingly dished praise, Nixon did just that at the end of Reagan’s first year in office right after Time Magazine declared Lech Walesa, the leader of the Polish anti-communist movement, “Man of the Year.”

“In my book, Time missed the boat: President Reagan should have been Man of the Year,” Nixon wrote to Reagan.