It’s a beautiful irony that Ottessa Moshfegh’s readership, consisting of the prim and proper elite set, gobbles up her highbrow depravities, and it’s all the better that she seems to get off on it. You will read about a drugged-out woman who sleeps for a year (My Year of Rest and Relaxation) and an alcoholic sailor suffering from a traumatic brain injury (McGlue) and a plethora of self-destructive young women who dive headlong into the urban squalor that surrounds them (Homesick for Another World), and you will like it, Moshfegh says with the grand bemusement that has come to define her.

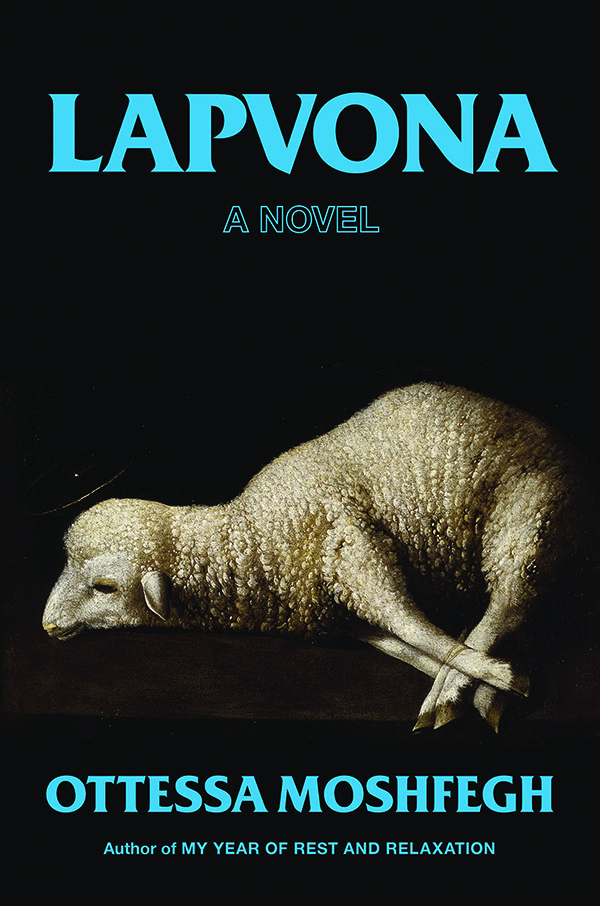

The great writers craft their literary shticks with as much focus and care as they do the actual craft of writing, and Moshfegh is no different, which is what makes her one of our few living masters. The work and the construction of the persona that delivers it play off one another, often creating jarring juxtapositions — such is the case with Moshfegh: She is the eminently stylishly disconnected woman (she’s not on social media) who is so connected with her own psychic darkness that only she can understand our current condition. It’s a tremendously effective literary shtick, and one that readers and critics alike have embraced, but with her latest novel, Lapvona, which takes place in the titular medieval village, Moshfegh is pushing the limits of her singular depravity and daring her followers to stick with her. The result is a gratuitously violent and often disgusting novel that, while uneven, is a hilarious thrill to read. I cringed and was grossed out on several occasions, but whenever I thought of Moshfegh’s pristine readership having to stomach cannibalism or a beheading, I couldn’t help but crack up. She’s a master, all right, I thought.

The fictional village of Lapvona, ruled by Villiam, a bumbling and less than regal lord with a “long, crooked nose and cheeks that were pitted with scars from a rash that still often broke out across his face,” is the perfect backdrop for Moshfegh’s longtime fictional project: the gleeful examination of the depths and contours of human misery. Lapvona’s plot hinges on the abusive relationship between Jude, a brutish lamb herder, and his 13-year-old son Marek, a “small boy” who “had grown crookedly, his spine twisted in the middle so that the right side of his rib cage protruded from his torso.” The father and son, who live on the outskirts of town and whose “pasture was at the foot of a hill, on top of which sat the large stone manor,” where Villiam resided, are outsiders in a town at the edge of the world. Marek, a child of incest (which accounts for his deformities), and Jude, who beats his son during bouts of self-loathing rage, have forged a dysfunctional relationship on their shared obsession with the woman whose absence hovers over their lives like a specter — Agata.

Jude told Marek that his mother, Agata, had died during his birth, but the truth was that she’d run off after catching a glimpse of the deformed child. Marek romanticizes the mother he never met, and Jude, who’d kidnapped the pregnant and tongueless Agata, who’d been impregnated by her bandit brother, after finding her beaten in the woods, despises her for escaping his clutches. Marek is a bastard, but he doesn’t know that he’s an incest bastard, nor that his father, whom he idolizes despite the beatings, is of no blood relation whatsoever. But the reader knows every last disgusting lie and detail; Moshfegh makes sure of it. Lapvona, after all, isn’t about the plot or even the characters and their development — there is none — but about an author’s desire to test the willingness of her audience to go along for the ride. The book isn’t an outright troll, but it’s surely trollish in spirit, especially as the depravity continues unabated for hundreds of pages, the thin characters all but disappear, and all that remains is Moshfegh and her suffocating authorial control.

Moshfegh is less an author than a narrative god in Lapvona, as she makes clear with her usage of the omniscient third-person point of view. The great writers are careful to craft narratives in which their characters have the appearance of agency. But in Lapvona, Moshfegh dispels that illusion. These aren’t characters who will change and come to grand epiphanies, but simply Moshfegh’s imaginative playthings who will suffer continuously at her hand. A reader will either find the numbing brutality in Lapvona pointless and dislike the novel, or find it, as I did, strangely hilarious in its commitment to meaningless depravity.

Moshfegh establishes the novel’s brutal framing early on, when Jacob, Villiam’s son and Marek’s distant cousin (Villiam and Jude share a great-grandfather), ends up atop a cliff. Jacob, a handsome prince who only leaves the manor for hunting trips and the occasional excursion with Marek, doesn’t suspect that his cousin has brought him to the top of the cliff for nefarious reasons. There is no tension to the lead-up, as the boys chase “cliff birds,” nor is there any surprise when Marek, a passive punching bag until this point in the novel, hurls a rock at Jacob, who predictably falls off the cliff. Lapvona’s theme, if such a word can even be attributed to such a cold and calculated novel, is perfectly encapsulated by the passage that follows Jacob’s fall: “Had God seen? Marek looked around. The wind stilled for a moment, then stirred again. There were no cliff birds, no nests on the cliffs. Marek had lured Jacob up for nothing. A joke, he’d thought.”

Moshfegh’s elite readership begrudgingly stomachs her brutally nihilistic point of view because it is often assumed to be in service of indicting contemporary culture and its atomizing qualities. Moshfegh, her readers and enchanted critics say, is shining a light on capitalism’s brutality through her nihilist lens. But such an argument is useless when it comes to Lapvona, a novel that takes place outside modernity and in which societal structures are nonexistent. In Lapvona, ideology or America or heteropatriarchy or whatever other mumbo-jumbo cannot be blamed for the village’s ills, because all that exists are the brutal realities of physical existence. The modern elite reader, so swaddled in expert-approved ideologies that explain human dysfunction, is having trouble with Lapvona because its thesis is that humanity is inherently animalistic and savage. It is not our ideologies or a commitment to faulty aesthetics or even the manipulations of a charismatic charlatan that lead us astray, but our very nature. Marek pushed Jacob off the cliff as a joke. And when Jude takes his murderous son to Villiam’s manor to face the lord, the ultimate cosmic joke occurs: Villiam doesn’t kill Marek in an act of revenge but has him replace his dead son. A lord cannot be without a son, so Marek, deformed and murderous and distantly related to Villiam, simply becomes the new son. This is what it means for a beloved author to push her loyal readership to the limit; this is Moshfegh taking her literary shtick to its logical endpoint.

After Marek moves into the manor, Moshfegh proceeds to ratchet up the squalor and depravity to such a degree that Lapvona’s plot becomes mechanical in its misery. Relentless awfulness, in the form of a monthslong drought that befalls the village, which forces its denizens to turn to cannibalism. If you’ve kept up by this point, the novel’s shock value has worn off, and there’s nothing left to do but wonder if Moshfegh will somehow tie together all the depravity and stick the landing. The problem is that Moshfegh attempts to tidy it all up with heavy-handed plotting, which is why Agata reappears pregnant with a “Christ child” after years of living in a nunnery. She moves into the manor, reuniting with her son after 13 years and setting off a series of contrivances.

As Lapvona reaches its final third and the inevitable narrative closure required of novels forces her hand, she leaves behind her authorial god mode and takes on that most boring of roles: troubleshooting. Moshfegh, clearly bored with petty novelistic concerns after shunning them for 300 pages, even resorts to a deus ex machina (in the form of a poisoned bottle of wine), and Lapvona, one of the bloodiest and untidy books I’ve read in recent years, ends as tidily as your typical airport thriller. In the end, Moshfegh wrote herself into a corner, but her commitment to her vision of endless brutality makes for a radically unconventional read for three-quarters of a novel. An imperfect Moshfegh novel, nevertheless, is better than most other novels.

Alex Perez is a fiction writer and cultural critic from Miami. Follow him on Twitter: @Perez_Writes.