Nikki Haley was picked to respond to President Obama’s State of the Union Address, and she used the opportunity to scold Donald Trump.

The South Carolina governor warned Republicans against listening to the “angriest voices” on the political scene. When moderators asked Trump about those comments in the South Carolina debate two days later, Trump mulled the charge for a moment before responding.

“I will gladly wear the mantle of anger,” Trump said. “I’m angry because our country is a mess.”

If you want to know why Trump gets a third of Republican support in national polls and leads in 49 states, look at his mantle of anger.

The appeal of anger, although it’s not “anger,” exactly, goes beyond Trump: Bernie Sanders has grumpily yelled himself into first place in Iowa and New Hampshire polls, over the supposedly inevitable Hillary Clinton. Specifically, he’s done it by tying her to Washington insiders and special interests who are “rigging the game” against the regular guy.

A huge swath of the electorate is angry because they agree that the country “is a mess” and the game is rigged. They think it’s self-evident, as Trump says, that “the American Dream is dead.”

For many, the predominant feeling is pessimism rather than anger. Attend a Trump rally or a Sanders rally, and you’ll see less anger than excitement. They’re excited because they think they’ve found someone who stands for them, and with them. And the clearest sign of standing with them: declaring that the game is rigged and that America is a mess.

This pessimism sounds odd inside the Beltway, and among most Americans with college or graduate degrees. Most politicians, in both parties, operate in circles where the American Dream is alive and well. And if the game is rigged, it’s rigged in their favor.

Supporters cheer during a rally for Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. (AP Photo)

Everything is awesome!

“Anyone claiming that America’s economy is in decline,” President Obama said in his recent State of the Union, “is peddling fiction.”

Obama can point to plenty of data: Gross domestic product has grown every quarter for seven years, sometimes by a lot. The unemployment rate has been falling since 2010 and is down to 5 percent. The stock market, even counting its recent struggles, is up more than 150 percent in the Obama years.

The housing market in many cities has recovered. Crime rates, even after a 2015 uptick, are way down. Lifespans are longer.

But go to upstate New York or upstate South Carolina. Go to central Pennsylvania or to Lowell, Mass. In these places, Trump Country, the supposed “fiction” of economic decline seems all too real.

“You don’t have the chance to make good money anymore,” one retiree said after a Trump rally in Rock Hill, S.C. “Wages have collapsed.”

Jeff Mason works six days a week. He drives a truck, delivering produce around the suburbs of Charlotte, N.C., Mason, in a thick hooded sweatshirt, holds up his meaty hands. “I got callouses on my hands, and they’re nasty.”

He’s a Trump supporter. He tells me his work history, but you wouldn’t call it a career. During the recession, he found work in the Pittsburgh area towing foreclosed cars. He was a repo man. There was plenty of foreclosing in the recession, but the work gnawed at his conscience until he quit. But “there was no jobs” in Pittsburgh, so he had to move his family down to South Carolina. “I spent six months looking for a job.”

Mason makes less than $14 an hour, he tells me. “I’m tired of getting shafted and not making good money. What happened to the $20-an-hour jobs? They’re gone.”

You used to be able to graduate high school, get a job, work hard and things would work out in the end. You could raise a family on factory wages. That’s gone. And it’s gone because of policies pursued by elites who benefit from them.

Good jobs have gone to China, and immigrants are driving down wages, is the refrain in Trump country. “Close the borders. Send ’em back home,” Mason said. “Let’s get jobs here first.”

“One in seven people in this country today are foreign-born. In 1970 it was one in 21,” Bob Garrett, Jr., said. “There’s too many immigrants in this country, and not enough jobs, not enough good jobs. Not enough jobs where people can actually make a living wage.” The victim: “The average, blue-collar American.”

Meanwhile, six of America’s 10 wealthiest counties are in the Washington, D.C., area, the Clintons are getting six figures for a speech and Wall Street gets a bailout.

Decline and fall

Just as the progress proclaimed by Obama and felt within elite circles goes beyond economics, so does the sense of decline in downscale parts of the country.

I asked Stacey, in South Carolina, what her “Make America Great Again” hat meant to her. What is it about America that is less than great? “It’s nothing like it used to be … Culturally, morally, economically, in every way.”

Ken Armstrong wore both a hat and a scarf adorned with “Make America Great Again.” When I asked him why he supported Trump, he told me of a conversation he had a few years back with a park ranger. “He said to me, ‘If you lived in the ’60s, you’ve probably seen this country the best it will ever be’ … Over the years, I’ve watched the political waves continue to prove it to be true.”

Armstrong put it in moral terms: “We had, I guess, a more God-fearing country.”

One woman at the Trump rally explained her Trump support with a story of her elderly mother. “The other day, she started crying,” the woman said. This was the first time she had ever seen her mother cry.

“The country’s just not like it used to be,” the 91-year-old said through tears. She recalled an America more infused with neighborliness and patriotism. “People helping each other, having pride in who we were.”

“I will gladly wear the mantle of anger,” Donald Trump said. “I’m angry because our country is a mess.” (AP Photo)

“I just think there’s a consensus out there that America’s not as great as it once was,” Garrett said. Young people, he argued, don’t see the decline because they never “had the opportunity to live in America when it was great. I have had that opportunity, and I don’t want to see our country go down the tubes, and I’m afraid that it is.”

His father recalls widespread patriotism in the 1940s and ’50s. “It was really great to be an American, and it’s just disintegrated over the years … It’s not the same America, and I would like it to get back … People have no respect for the traditional things we did back then.” He said he realizes change is inevitable, but, “I liked it better then. It was better to be an American.”

No hope or change

Hillary Clinton, in January’s Democratic debate, decided she was running to be Obama’s third term. She took ownership for his economic record, and his “reforms.”

But many Democrats haven’t thrived in Obama’s economy. “He screwed us,” coal miner Shelley Brannon told the Washington Post’s Dave Weigel. Weigel documented the plight of the downscale white Democrats in West Virginia and other pockets of rural America.

Bernie Sanders argues that these voters have no home in the GOP. “We have millions of working-class people who are voting for Republican candidates whose views are diametrically opposite to what voters want,” Sanders said.

Sanders’ brand of socialism turns off the most powerful parts of the Democratic Party. The Chuck Schumer and Hillary Clinton wing of the party, Wall Street and K Street Democrats, dismiss Sandersism as obsessed with ideological purity. Who needs single-payer healthcare when we have subsidies for Big Pharma and private insurers? Why break up the big banks when you can instead put them on a leash with some subsidies and some protective regulations?

And the Democrats’ culture warriors, embodied by the Black Lives Matter movement and the abortion lobby, don’t like Sanders’ version of identity politics. Identity politics is supposed to be about skin color, sexual orientation, gender and these days gender identity. Making identity politics about class is gauche in elite Democratic circles.

So Sanders has found his own ignored slice of the electorate: along with the true-blue progressives put off by ruling-class, corporatist millionaires like Clinton are the blue-collar whites who resemble the old-school populists of centuries past.

Bernie Sanders has grumpily yelled himself into first place in Iowa and New Hampshire polls, over the supposedly inevitable Hillary Clinton. (AP Photo)

But why The Donald?

So where does a billionaire Hillary Clinton donor proud of his New York values fit into this picture?

Donald Trump has earned his following, and his detractors, mostly through his immigration rhetoric. He’s lumping all immigrants in with rapists, pledging to build a wall and calling for a moratorium on Muslims entering the country. But four years ago, Trump sounded less like Pat Buchanan and more like a typical businessman.

Trump blamed Mitt Romney’s loss in 2012 largely on Romney’s “mean-spirited” policy of pushing immigrants to “self-deport.” “It sounded as bad as it was, and he lost all of the Latino vote. He lost the Asian vote. He lost everybody who is inspired to come into this country,” Trump told Newsmax, the conservative website.

Immigration isn’t his only shift, of course.

Donald Trump is two things above all else: a performer and a businessman. As a businessman, he looks for investment opportunities, including underserved markets.

Trump’s campaign can be seen as a performance that serves an underserved political market, selling a good in high demand but low supply. And his market is perhaps best defined by subtraction.

The racial minority vote, especially black voters, is cornered by Democrats (80 percent voted for Obama in 2012). Religious conservatives turn to the Republican Party for their supply of pro-life and pro-family politics.

The wealthy have no shortage of suitors in both parties. Both parties also court middle-class soccer moms and dads. College students tend to be Democrats.

Donald Trump blamed Mitt Romney’s loss in 2012 largely on Romney’s “mean-spirited” policy of pushing immigrants to “self-deport.” (AP Photo)

After the two parties divvy up or fight over these populations, there remain the leftovers: mostly working-class whites who aren’t part of the religious Right — no college degree and typically these days not inside major cities.

That’s Trump’s market, and here’s his act: populism that includes protectionism and immigration restriction, with doses of nationalism and nostalgia. The wonder isn’t that Trump was able to attract so much attention and support with this message to this market. The wonder is that both parties left this market untapped for so long.

‘The missing white voter’

It was obvious by Election Day 2012.

Mitt Romney had admitted, in his private moments, that he would not pursue the poorest 47 percent of voters. Those making below median income, Romney seemed to reason, were lazy dependents who could not be convinced to “take personal responsibility and care for their lives.”

Romney was wrong to assume the 47 percent were all die-hard Democrats. Much of this group includes the Reagan Democrats. Many were people suffering in the economy that Obama had wrought.

Romney was correct, in a self-fulfilling way, that the 47 percent wouldn’t vote for him. A big chunk of them stayed home. In the days after Election Day, this bloc came to be known as the “missing white voter.”

While the black vote, the Hispanic vote and the Asian vote all grew from 2008 to 2012, the white vote dropped by 4.6 million, despite growth in white voting-age population. Pollster Sean Trende mapped the counties where turnout underperformed, and he found a diagonal slash from rural Maine down through Appalachia, the Rust Belt and into Oklahoma and New Mexico.

The voters who stayed home “tended to be downscale, blue-collar whites,” Trende concluded. These were Reagan Democrats. They were Ross Perot voters. And they are Trump supporters now.

Trump fares 21 percent better among those who haven’t voted in the past four elections than among those who have been voting through the Bush and Obama years, according to a Reuters/IPSOS poll.

Trump, it seems, has found the missing white voter.

While the black vote, the Hispanic vote and the Asian vote all grew from 2008 to 2012, the white vote dropped by 4.6 million, despite growth in white voting-age population. (AP Photo)

Whose American dream is dead?

When Trump talks about the American Dream being dead, it can sound absurd. First, he makes some silly and dated claims. He likes to rhetorically ask: “When did we beat Japan, at anything?”

America is beating Japan at many things these days. Indeed it is beating Japan at most things, including GDP, birth rate and smartphones. Yet Trump’s other complaints follow a similar line.

“We’re losing our jobs to everybody,” Trump says. “To places like China. Vietnam is the new hot one, they’re taking our jobs. Mexico always. They’re outsmarting us at every turn, and we don’t seem to be able to do it.”

These lines, and the anti-trade, closed-borders arguments that accompany them, earn almost universal scoffing in elite circles. You can’t find a think tank, conservative, libertarian or liberal who supports protective tariffs of the sort Trump demands.

The elites of both parties similarly agree with the business lobby that more immigration is needed.

But Trump’s heterodox policies are secondary. It’s his diagnosis that puts him most at odds with the bipartisan elite, and that endears him to so many missing white voters.

Different groups in America have very different trajectories over the past few decades.

The median woman with a professional degree earns 27 percent more than her counterpart in 1991, adjusted for inflation. And professional degrees are much more open to women today. If you’re a man with some amount of college education, but no degree, you’re making 11 percent less than your counterpart in 1991. When you consider that black males’ income is up 20 percent in that period, and Hispanic males’ income is up 14 percent, you realize how negative the picture has been for white men with no college degree.

Downscale white men are even dying more. Sociologists Anne Case and Angus Deaton recently released a study finding “a marked deterioration in the morbidity and mortality of middle-aged white non-Hispanics in the United States after 1998.”

Skyrocketing causes of death among this population: overdoses of drugs and alcohol, suicides and chronic liver disease. Notably, Case and Deaton had tremendous trouble finding a journal willing to publish this data.

Worrying about white people problems is seen as uncouth, but the white working class clearly has problems.

The causes

The causes of white male stagnation are complex and infinitely debatable. Some point to the erosion of white male privilege. Others point to immigration. Some point to free trade and mechanization of manufacturing. Some point to women increasingly joining the workforce.

These economic shifts, which go back to 1970 or so, are all cultural shifts. When women enter the workforce, this has to have a downward effect on wages. When those $20-an-hour factory jobs disappear in the name of free trade, a man without a college degree finds it hard to raise a family anyway. So now how will he find a wife?

This process continues for decades, and everyone declares it “progress.” Free trade means cheaper goods and more peaceful international relations. Women’s liberation means equality and security. Racial progress helps dim the stains of slavery and segregation.

What’s the forgotten white man to do? Republicans offer up religion and cheap goods at Wal-Mart. Democrats offer up welfare. Neither of these offerings appeal much to these voters.

In his 2012 book Coming Apart, Charles Murray tells the story of Fishtown, a white, working class Philadelphia neighborhood. Before 1970, the community and its people had jobs, family and purpose.

By the 1990s, the religious affiliation had worn paper thin. Marriage was becoming rarer. “In 1970, 81 percent of families with children under age 18 were still headed by married couples. Over just the next 10 years, that figure dropped to 67 percent.”

I asked Stacey, in South Carolina, what her “Make America Great Again” hat meant to her. What is it about America that is less than great? “It’s nothing like it used to be … Culturally, morally, economically, in every way.” (AP Photo)

Low-skilled men were beginning to become irrelevant thanks to all the economic and social progress.

The Left had an answer, but Fishtowners were uninterested. “Pride prevents them from taking advantage of social services,” one Philadelphia welfare agent wrote. “For them to accept these services might be to admit that they’re not all they claim to be.”

Unsatisfied with the consolation prizes of cheap Chinese-made goods or government handouts, it’s no surprise many of these voters dropped out of two-party politics.

Reagan briefly brought some back into the fold. So did Ross Perot. Romney pushed them away.

Courting the working class

In recent years, some Republicans made efforts to bring these voters back. Rick Santorum’s efforts were the most earnest.

In 2012, Santorum ran as the blue-collar conservative, and he had great success. He never had much of a chance of winning the nomination, but it was telling that he ran such a clear second place and won so many states.

After Romney lost to Obama, Santorum spoke directly to the concerns of the missing white voter. On the notion, beloved by conservatives, that a rising tide lifts all boats, Santorum argued, “If your boat has a hole in it, it’s not going to rise.”

In an interview with the Washington Examiner‘s Byron York, Santorum said, “So you have to talk about what can we do for people who have holes in their boats. And you know what? In America today, that’s a lot of folks. They have all sorts of issues that they have to overcome to be successful. Whether it’s family issues, whether its physical or mental health issues, whether it’s skills issues, education issues — all of us have holes, right?”

Marco Rubio adopted the platform of “reform conservatives,” who aimed to put conservative policies at work for ordinary Americans who were struggling. Rubio offered larger child tax credits for the middle class.

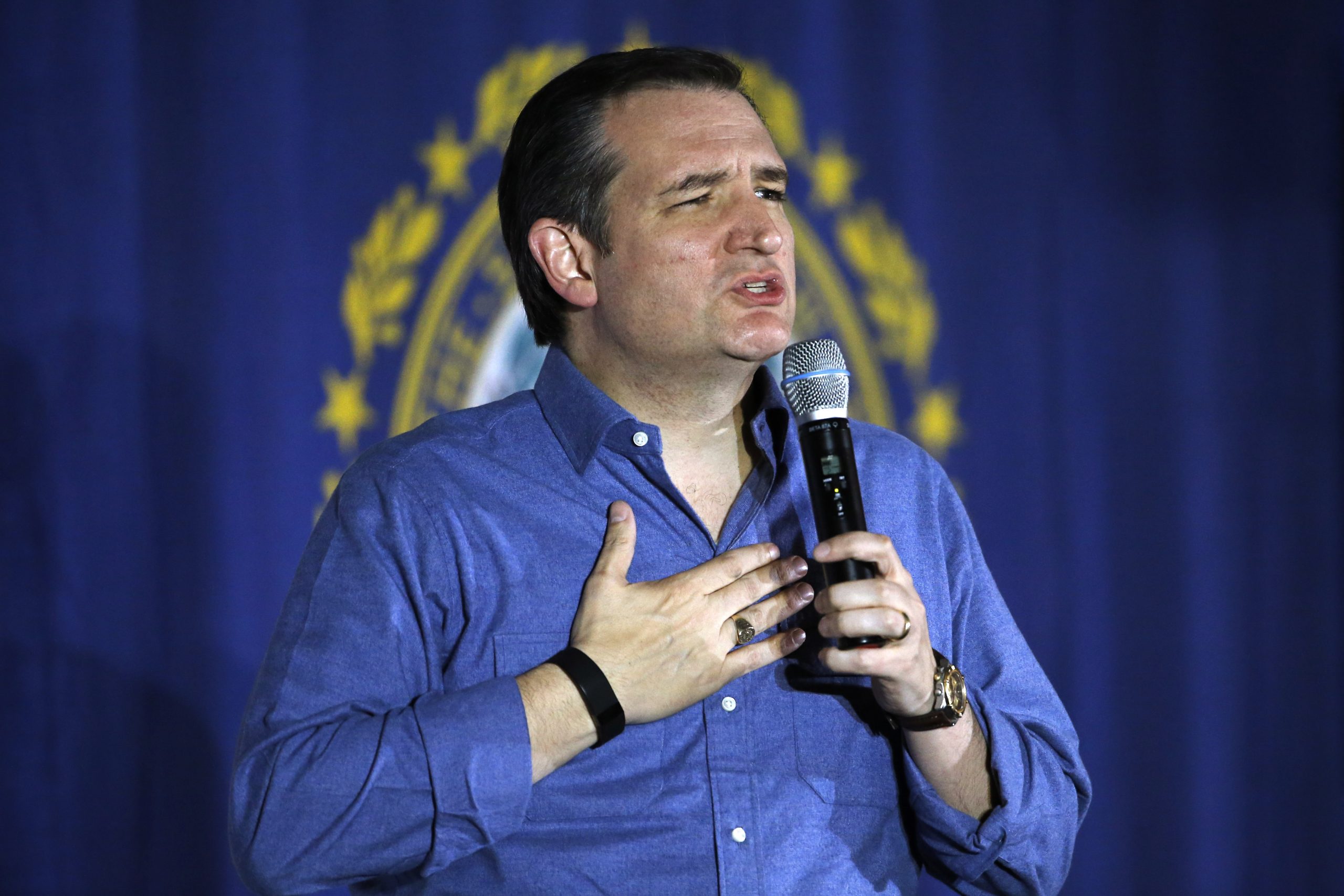

Ted Cruz offered warfare against the “Washington cartel” that was enriching itself at everyone else’s expense. He battled the Republican leadership (burning many Beltway bridges) and corporate welfare like the ethanol mandate (offending many Iowa mandarins) and the Export-Import Bank.

But when a populist furor is brewing, a corporate tax break for manufacturers, a family tax credit here and a policy fight there doesn’t carry the weight of demagogic bombast — hence Trump.

Two-thirds of Donald Trump’s precinct captains in Iowa indicated recently that they had never attended a caucus. These are the disaffected, the disenfranchised.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, offered warfare against the “Washington cartel” that was enriching itself at everyone else’s expense. (AP Photo)

“The thing about appealing to people who don’t usually vote,” political scientist Thomas Holbrook told The Daily Caller recently, “is that they don’t usually vote.”

Trump has tapped into the voters who have tuned out of politics. He’s gotten them to attend rallies, wave signs, respond to pollsters and buy hats and scarves. Will they turn out on Election Day?

If Trump loses Iowa, as polls suggest he will, will they fade away again?

Finally, if Trump flames out, and if Sanders succumbs to Clinton’s K Street juggernaut, will other Democrats (Elizabeth Warren in the future) or Republicans (Ted Cruz now or in the future) be able to harness the populist furor?

Or will these forgotten voters slip back into the shadows?