Thomas Piketty’s bestselling and widely-cited book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, mischaracterizes inequality, according to a new paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Daron Acemoglu, of MIT, and James Robinson, of Harvard, criticized Piketty’s book, writing that Piketty’s arguments give a “misleading characterization of the true nature of inequality.”

The authors compared Piketty to Marx in their critique, writing, “Piketty goes wrong for exactly the same reasons that Marx, and before him Ricardo, went astray: these quests for general laws ignore both institutions and politics, and the flexible and multifaceted nature of technology.”

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Piketty argued that inequality rises when the rate of return on capital is greater than the rate of economic growth.

Acemoglu and Robinson say Piketty fails to show even a correlation supporting his thesis, let alone causal evidence. “It is quite striking that such basic conditional correlations provide no support for the central emphasis of Capital in the 21st Century,” the authors write. They admit that a higher rate of return on capital probably increases inequality, but that many other factors have a larger impact on inequality.

Acemoglu and Robinson essentially write that Piketty’s argument is oversimplified. Economic laws are often written too generally, so that they ignore the influence of governments and economic policy. For example, the rate of return might exceed the rate of economic growth, but economic policies might ensure the gains of that growth go to the lower class, not the top 1 percent.

Over-generalized economic laws also ignore the ability of technology to shape society, especially the way wealth is distributed. Again, the rate of return on capital might exceed the rate of economic growth, but technology gains might mean those economic gains go to the lower class.

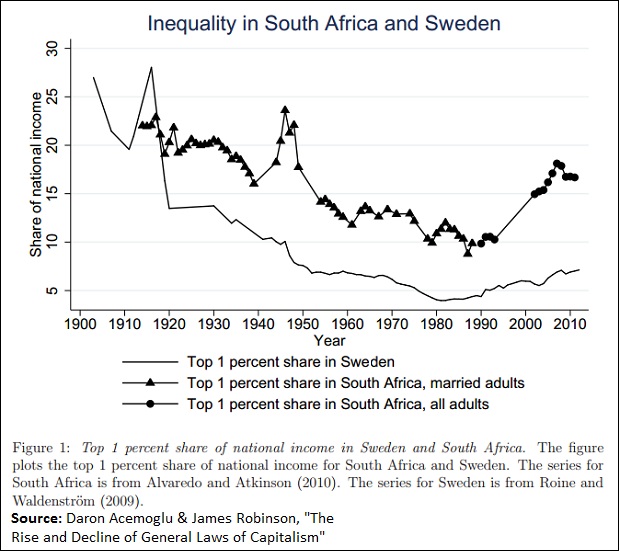

Acemoglu and Robinson then examine Sweden and South Africa. The authors say the data on income gains by the top 1 percent in these countries show a distorted view of inequality that misses what happens to the middle and lower classes.

For example, data show the top 1 percent’s share of income in South Africa was at its lowest point just before the end of apartheid, implying that inequality was low during apartheid. However, apartheid was explicitly designed to hurt lower-class blacks and alternative measures show inequality was high during apartheid. Just after the end of apartheid, the top 1 percent’s share of income rose, even though alternative measures showed inequality on the decline.