With growing enthusiasm for lifting the federal minimum wage in Congress, it’s time to consider some data on wages and differences in the cost of living across the 50 states. The Raise the Wage Act, introduced by Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., in January with broad support from his party, would raise the federal minimum wage from the current $7.25 per hour (where it has been since 2009) to $15.00 in 2024.

Anyone fresh to these shores, reading this last sentence with no knowledge on the topic, would likely be shocked: “Do you mean to say the U.S. minimum wage is $7.25 and has not been changed in 10 years? How do entry-level workers make it?”

Well, there is far more to the story. First off, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, just 542,000 out of 84 million U.S. wage earners were paid $7.25 per hour in 2017 — less than 1%. Of course, any one of these workers would be happy to see a paycheck based on a $15 hourly wage.

Remember, though, that any state or municipal government can independently establish its own unique minimum wage laws. As of January, some 30 states and the District of Columbia had minimum wage mandates exceeding the federal level, from a high of $13.25 in D.C. to $12.00 in California and Massachusetts to $11.10 in Colorado and New York to $10.10 in Connecticut and Hawaii.

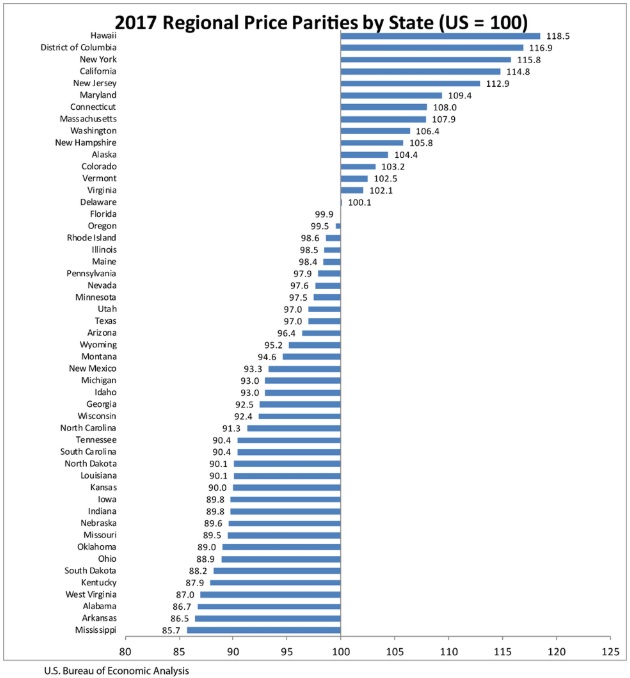

As might be expected, differences in the mandated state wage levels closely reflect differences in state cost of living. Consider the comparative cost-of-living data in the accompanying Department of Commerce chart. Data points for each state show how that state’s cost compares with the U.S. average. Hawaii, the District of Columbia, New York, and California are positioned at the top. Their living costs are more than 14% higher than the U.S. average. As just noted, their minimum wage laws are also substantially higher than the $7.25 U.S. minimum.

At the lower end of the data, one finds states with substantially lower living costs than the U.S. average: Mississippi, Arkansas, and West Virginia. The minimum wage rates in those states are $8.25, $7.25, and $9.25 respectively. The federal $7.25 minimum applies in another large group of generally lower-cost states: Alabama, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Of course, each state and locality is unique, and there is more going on in each than just cost-of-living differences. But generally speaking, market-determined wages that influence state minimum wage laws reflect those cost-of-living differences. Wise politicians know this.

So, what’s going on in Congress? Why not leave it to the states to set the floor for wages? After all, those at the state level would seem better situated to assess local living and other relevant costs. Is it all a “sound and fury signifying nothing?” Probably not.

Take a second glance at the cost-of-living chart and identify which states will be punished most in the struggle for economic development if their minimum wage laws are required to be set at $15 an hour. If that came to pass, lower-cost states would lose a key competitive advantage (affordable workers who aren’t saddled with America’s highest costs for housing and other goods) and become less-attractive for the business development they need.

With a $15 minimum wage, high-cost-of-living states would be less concerned about the outmigration of people, industrial plants, and corporate headquarters to more affordable areas of the country. One can debate whether that’s a good or bad thing, but it would mean the rich stay richer while the poor stay poorer.

There is one more matter to consider. Efforts to assist young people earning $7.25 an hour by mandating that their employers ante-up $15 will surely help some of them. But such mandates will just as surely lead some employers to cut hours, close high-cost operations, look for ways to automate, and generally hire fewer of these young workers who are in need of money and experience.

Wise politicians know this, too.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business & Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.