On Sept. 18, 2012, in Rome, 58-year-old Karen L. King, a senior Harvard Divinity School professor specializing in early Christian history, disclosed to a conference of Coptic scholars — experts in ancient Egyptian Christian texts — that an undisclosed person had given her access to a scrap of papyrus stating in Coptic, “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife.’” The fragment, which King said dated to the fourth century, was tiny, the size of a business card, bearing only eight lines of crude, truncated script, plus a few scattered words on its reverse side. But King had given it a grandiose name: the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. It was a bombshell revelation, giving credence to Dan Brown’s bestselling 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code, whose plot involved a marriage between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. The media duly poured out rivers of speculation over what this discovery could mean for the future of Christianity.

This disclosure had been carefully timed and orchestrated by King and Harvard’s publicity machine, which granted reporters exclusive interviews with her before the conference, so that news stories were breaking even as she spoke. One of those reporters was Ariel Sabar, writing a magazine piece for the Smithsonian Institution, which in addition had a television documentary about the papyrus ready for release. Also ready to go was a 52-page article by King for the Harvard Theological Review, in which she contended that the words on the papyrus were likely a translation of a lost second-century Greek tract from a dissident theological tradition that held that Jesus had been married, probably to Mary Magdalene (the papyrus mentions a “Mary”).

Within days, however, scholars knowledgeable about Coptic texts had looked at online images of the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife and deemed it a forgery: It was a pastiche of phrases copied from the Gospel of Thomas, a well-known collection of sayings attributed to Jesus by the Gnostics, heterodox Christians who flourished in Egypt and elsewhere from the second to the fourth centuries. Indeed, the papyrus preserved a typographical error in a Coptic-English interlinear translation of the Gospel of Thomas posted online in 2002 by Michael Grondin, a retired computer programmer and amateur Coptologist. Experts also noted that the clumsy handwriting in King’s fragment resembled no known fourth-century Coptic script. Radiocarbon tests belatedly conducted by Harvard dated the papyrus scrap to the eighth century, long after the Gnostics had disappeared from Egypt. The Harvard Theological Review, which had defended King’s article during the forgery furor, published a drastically shortened version of the article in 2014, in which King retracted her assertions about a married-Jesus tradition but continued to maintain the papyrus was authentic.

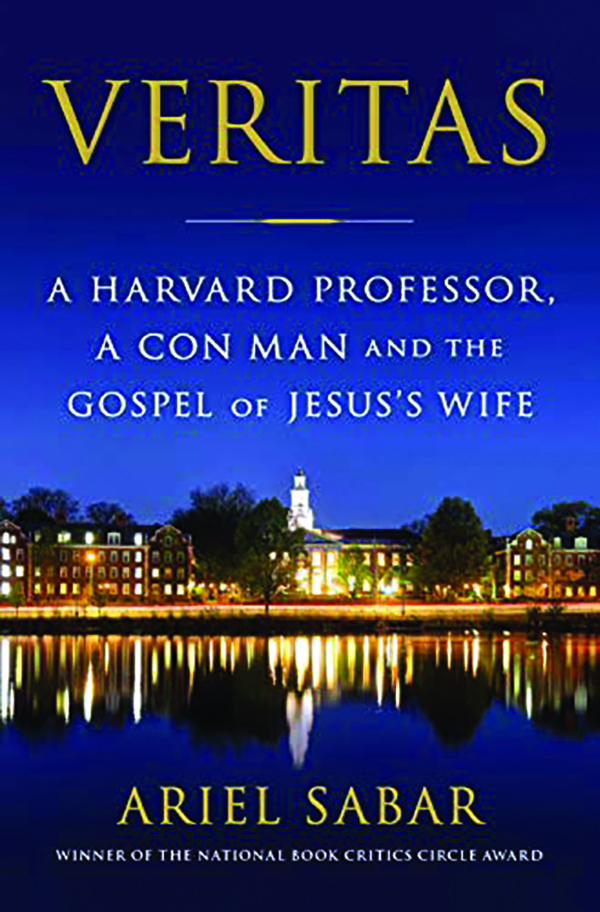

Around this time, Sabar, whose 2012 article in the Smithsonian magazine had mostly channeled King, embarked on some genuine investigative reporting that enabled him to find out who the owner (and thus the likely forger) of the papyrus was, as well as damning new revelations about King’s careful and secretive staging of the “verification” process. The result was a dazzling piece of shoe-leather journalism, which appeared first in a 2016 article in the Atlantic and now, in deliciously greater detail, in Sabar’s new book, Veritas. I myself had covered the scholarly unraveling of King’s revelations in articles for the Weekly Standard, but I devoured Sabar’s book practically in one sitting. King, in her Harvard Theological Review article, had revealed that the owner said he bought the papyrus in 1999 from a (conveniently dead) German auto-parts manufacturer, H.U. (for Hans-Ulrich) Laukamp, who had supposedly smuggled it and other papyri out of East Germany in 1963. The owner had also given her photocopies of apparent early-1980s correspondence involving two professors of Egyptology at the Free University in then-West Berlin, also conveniently dead, one of whom seemed to refer explicitly to the papyrus of the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. Another reporter, Owen Jarus of Live Science, had looked up records for Laukamp, who had lived and apparently run a branch of his business in Venice, Florida. He discovered that Laukamp had been minimally educated and had no interest in antiquities. But it was Sabar who tracked down Walter Fritz, a 50-something Bavarian immigrant living near Sarasota, Florida, who had been Laukamp’s business partner, and got him to talk.

Fritz proved to be quite the character. He mingled bits of truth and falsehood (mostly the latter) to Sabar after admitting that he owned the papyrus while denying that he had forged it. He disclosed that he had studied Coptic (after lying about that to King) as a student at — guess where — the Free University, which he left without a degree after being accused of stealing a professor’s idea in a published paper. His career after that, pieced together by Sabar in numerous interviews in Germany and elsewhere, included heading the Stasi Museum in Berlin after reunification, until his abrupt departure when some Nazi memorabilia went missing, and then talking himself into partnership with Laukamp, whose business he allegedly drove into the ground. In Florida, he ran an online business selling dubious ancient items as well as an internet pornography operation featuring his wife having sex with various men.

The wife-pimping, schlock-art-hawking Fritz was an obvious mountebank, but Sabar saves his most damning assessment for King. Although she had a doctorate in religious history from Brown University and knew Coptic, she had no expertise in the technicalities of Coptic scripts and manuscripts. But she refused to let scholars who did have that expertise examine the papyrus, ignoring the warnings of colleagues and a peer-review process for the Harvard Theological Review in which two out of three reviewers expressed doubts about the papyrus’s legitimacy. She steered testing of the papyrus to scientists with whom she had personal associations, tried to bar journalists from interviewing outsiders, and sought to block a critical response by another Coptologist to her Harvard Theological Review article. Worst of all, in Sabar’s estimation, she made no effort to investigate the scrap’s provenance. “Somewhere in her heart, it seemed, King knew that the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife was dead the moment anyone outside her influence looked too closely at it,” Sabar writes.

But King, who is now in phased retirement, didn’t seem to care. She had spent her entire academic career before Harvard hired her in 2003 affiliated with the Jesus Seminar, the organization of outré scholars with a mission to rewrite the traditional Gospels. Nearly all her publications before that date were with the Jesus Seminar-affiliated Polebridge Press, including her bestselling 2003 book, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala, timed fortuitously to appear alongside The Da Vinci Code. It, too, dealt with a Coptic fragment that King insisted represented an alternative tradition about Jesus and his relationship to Mary Magdalene. She wanted to “reinvent ancient Christianity,” Sabar writes — and she nearly did.

Charlotte Allen is a Washington writer. Her articles have appeared in Quillette, the Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and the Los Angeles Times.