Back in November, when General Motors CEO Mary Barra announced the closing of five underutilized North American manufacturing plants and the planned termination of 15,000 employees, President Trump threw a temper tantrum that must have rattled windows all the way to Detroit.

….for electric cars. General Motors made a big China bet years ago when they built plants there (and in Mexico) – don’t think that bet is going to pay off. I am here to protect America’s Workers!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 27, 2018

Later, cooler heads indicated that while a government bailout did cause GM to avoid bankruptcy, it did so without requiring assurances of future production and employment. Also, there are no direct GM electric car subsidies. Those go to consumers who purchase electric cars, not to auto producers.

Obviously, Barra faces a severe challenge. GM’s overall sales are falling. Auto consumers no longer line up to buy GM’s sedans and small economy cars. Trucks, SUVs, and crossovers are hot. The rest of GM’s line is not.

It’s not just a GM challenge. All major auto producers, to differing degrees, face a market-driven dilemma, one that has been brewing for a long time. When combined with cheap gas, pickup trucks and other large, roomy, and safer truck-like vehicles are the toast of the town. Smaller, cramped, and less-safe vehicles are just toast.

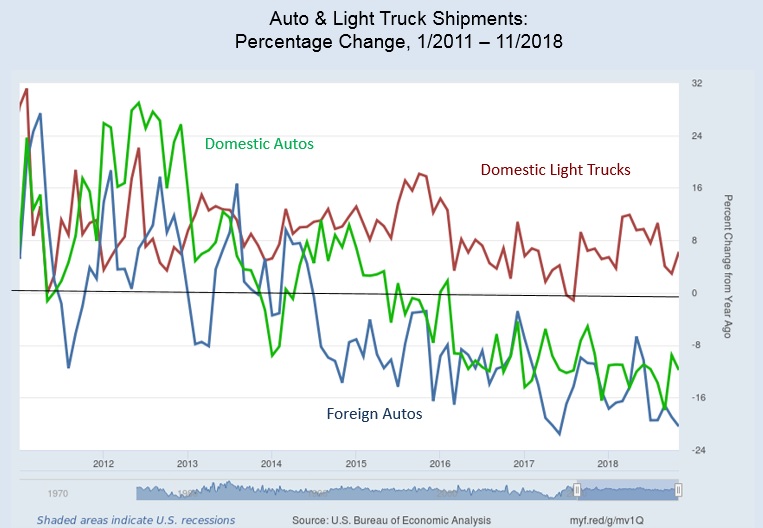

Look at the situation in the below chart, which shows U.S. annual growth in unit sales of light trucks (which includes SUVs) and domestic- and foreign-produced passenger cars from January 2011 through November 2018. Trucks and SUVs have maintained a positive growth path. Passenger cars have experienced sharply falling growth rates and, since 2015, rising negative rates of growth.

It’s plain to see that the U.S. auto industry’s problem does not relate to countering expanding shipments of foreign-produced passenger cars. All passenger car sales, no matter the origin, are caught in the same tailspin. Sorry, putting tariffs on foreign sedans won’t get the job done. The real industry dilemma is how to produce more light trucks, or anything else that U.S. consumers are happy to purchase.

Unlike the situation in the United States, Chinese consumers, located in the world’s largest auto market, are still eager to buy sedans and other passenger cars. GM’s Buick brand is one of the hottest badges going.

The chart’s data help to explain Barra’s market-driven logic for opening plants in China while shuttering U.S. sedan production. GM does not produce cars in China primarily for export back to the United States. Plant locations are driven by country-market considerations; capital is not so footloose as to allow for a chess game in which pieces can be moved anywhere on the board to form winning strategies.

Yet Trump seems to view the situation as a chess game, and suffers from a chessboard enigma that was described by Adam Smith in 1759:

Yes, Barra faces a challenge because she must find ways to satisfy consumers in markets who are free to pick and choose among a host of competing automotive products while searching for their happiness. Trump, on the other hand, faces an enigma. World markets for automobiles are far more complex than we can imagine. He faces a vast knowledge problem that cannot be communicated or resolved by sending out midnight tweets.

Meanwhile, Barra is addressing her dilemma, while Trump’s top-down desire to move America’s chessmen continues unabated. The resulting mix of actions does not augur well for rising prosperity, here or elsewhere.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business and Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.