As I noted earlier Monday, Mosul’s liberation from the Islamic State (ISIS) offers a key opportunity to the Iraqi government.

If Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi is able to rebuild the city and promote multisectarian cooperation, he’ll take a significant step forward to Iraq’s better future.

Still, the fight against ISIS in Iraq is not yet over. The group continues to control territory, and it retains the ability to launch attacks on Iraqi civilians. Additionally, as ISIS loses territory, its preference for deadly bombings against civilians will grow. Iraqi security forces will expect bloody attacks in the coming weeks.

The Iraqi government cannot sit idle in face of this evolving threat. And nor should the U.S.-led counter-ISIS coalition.

To keep ISIS on the constant defensive, our next step should be the retaking of the small border town of Al Qa’im.

Located on the Iraqi side of the Syrian border, Al Qa’im is a traditional smuggling center for cross-border trade. But these days the Anbari tribes who used to populate Al Qa’im have been pummeled by ISIS. Today, it’s a key facilitation hub through which ISIS personnel flow back and forth across the border. Taking Al Qa’im would disembowel the group by fundamentally denying its freedom of movement.

Fortunately, the task should not be that complicated.

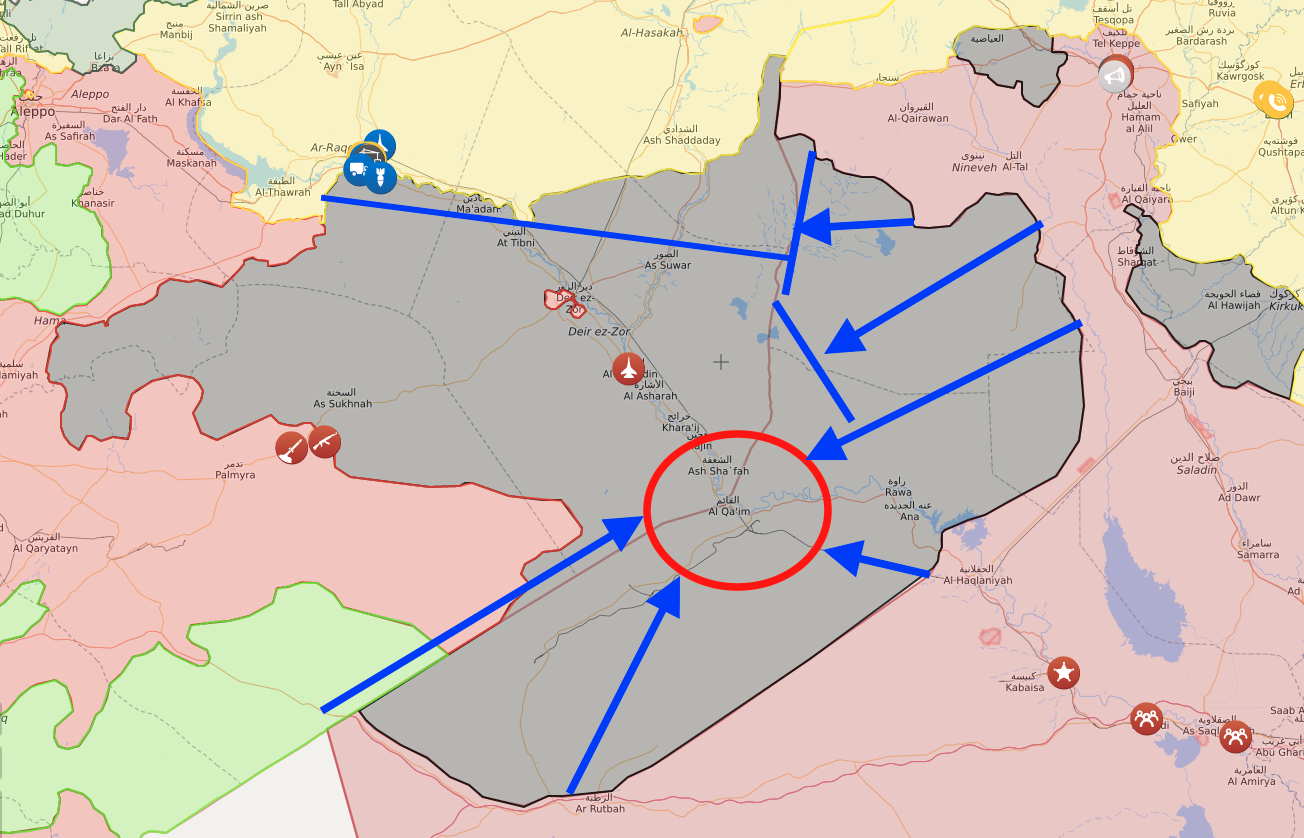

The map below illustrates my take, which borrows from the Iraq Live Maps template, on how the U.S. coalition and Iraqi forces could compress Al Qa’im (in the red circle) from the north, south, and east. The blue arrows indicate offensives, and the blue lines represents holding positions.

On the eastern Iraqi front, Iraqi army forces could push up the Euphrates river valley toward Al Qa’im, encircling or sidestepping ISIS-controlled settlements. Similarly, Kurdish and allied special operations forces would press against ISIS from the northeastern front, creating a holding position along the border. That would force ISIS into a northern death trap (the + marked area) in Syria, just north of the Euphrates.

Moreover, the starting point of the most westward blue arrow (just across the Syrian border) illustrates the U.S. and allied special operations forces garrison at At-Tanf. As I’ve explained, that position gives the U.S. great opportunity to push through the Syrian desert against Al Qa’im’s southern flank.

Finally, the long blue line in northern Syria represents the line of offensive against Raqqa. Those forces could act as a holding force along the northern area of the Euphrates river valley, requiring ISIS to dedicate units to prevent a further coalition push south and destroying any ISIS forces attempting to retreat westward from the border.

Regardless of what plan is employed (and of course, mine is only for basic illustration), the advantage of taking Al Qa’im cannot be underestimated. Not only would it deny ISIS the critical strategic node via which it claims a multination caliphate, but it would also strike a major blow to the group’s confidence. Forcing ISIS operational planners to focus on defense rather than offense, it would also restrain the group’s ability to plan and conduct attacks in Europe.