Reactions to Friday’s amazing announcement from the Bureau of Labor Statistics ranged from, “Now there’s evidence that the Paycheck Protection Program is doing its intended job,” to, “We are seeing the end of the coronavirus collapse.” Some now speculate that the hoped-for “V-shaped recovery” is on the way.

But what conclusions can we actually take from unprecedented numbers in a strange command economy? Not as many as we’d like.

If you haven’t heard, experts were surprised and some perhaps stunned to hear that a record-setting 2.5 million new jobs had been added to the nation’s payrolls in May. The unemployment rate, which was expected to climb to as high as 20%, fell from 14.7% to 13.3%. Indeed, the May diffusion index of 64% for all 258 industries, in which a number over 50% indicates economic expansion, shows that the economy does seem to be alive again.

By any assessment, the astounding employment gain has to be seen as good news for the 30 million workers added to unemployment rolls in the last 90 days. But that is not the same as saying that a “Goldilocks” economy, where everything seems just right, lies waiting just around the next corner.

No. Instead of drawing that conclusion, one must step back, look harder at the data, and recognize that the labor report reflects an abnormally strange command economy. Political actions taken to turn on previously closed economic sectors, as one might turn on the lights in a totally dark room, can generate sudden and dramatic changes.

Those who see the May employment gains as unlike anything ever observed in economic history might also realize that we have never before seen a command economy in the throes of attempting to regenerate itself. About 1.4 million of the 2.5 million job gains were for workers in eating and drinking establishments, of which most had just reopened. Many of those were part-time workers returning to part-time jobs. Some 40% of the month’s job gains were in part-time employment. With such narrowly focused job gains, this is hardly a valid indicator to use for assessing the economy’s overall health.

It’s also worth noting that while the eating and drinking job count was rising, hotel employment was still falling. There were good gains in construction, but that was also driven by some governors turning on the switch and allowing that sector to come alive. Meanwhile, construction activities in some other states were never turned off and probably, as a result, showed little surge.

Let’s face it: A command economy can generate some strange bumps in the night.

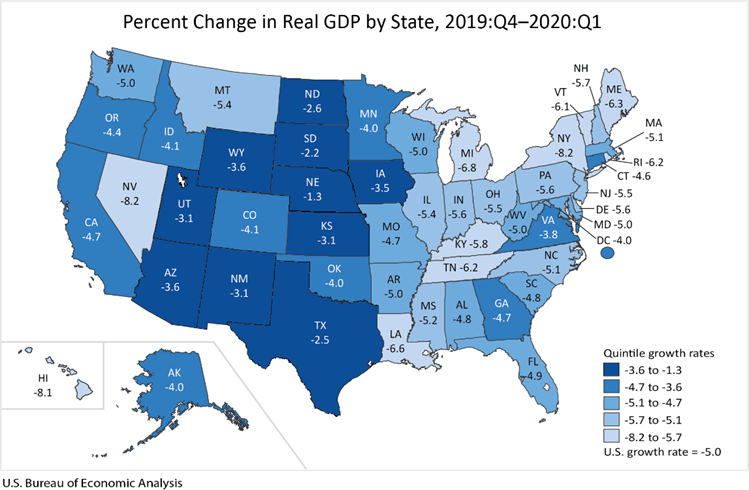

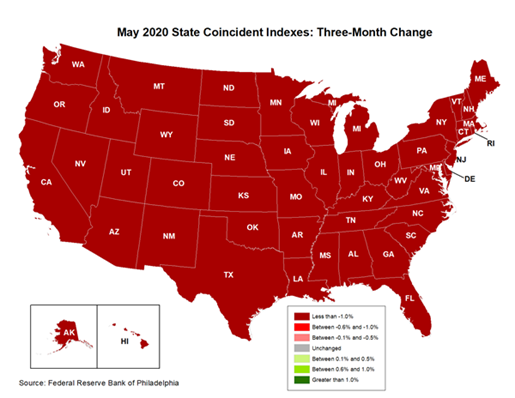

We get a feel for the strangeness of our times by eyeing the below state coincident indicators map produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia for the month of April (its most recent map). I provide the March map so that comparisons can be made.

Every state in the April map has the same dismal hue, meaning a more-or-less equally bleak situation for each of the 50 states. Unlike March’s picture, brighter shades are nowhere to be found. There’s not a smidgen of Goldilocks here. We are observing a picture of a coronavirus-infected command economy, one still waiting for enough of us to hit the gas and make it go from zero to 60 again.

So, what can we conclude from May’s labor situation report? Do the strong job gains mark the beginning of an accelerating economic recovery? Do the data tell us that we should expect to see a V-shaped recovery, not a U-shaped or a Nike swoosh-like path to future prosperity? I don’t think so, though the data do not deny such possibilities.

All that we can take from the report is that there were 2.5 million people added to the nation’s payrolls in May in a strange command economy. The related unemployment rate fell. Yes, things may look even better when the June numbers are produced, but the waters we are sailing on are too rough and choppy for us to draw conclusions about a future normal sea.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business and Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.