As I write this, Chinese and American trade negotiators are working to widen the door for movement of goods between the two countries. Meanwhile, American consumers may have just a few more days to shop for lower-priced Chinese-made goods.

On March 1, the 10 percent tariff now applied to a vast array of those goods is scheduled to rise to 25 percent. And surely, once again, the Chinese will retaliate. If we choose to put larger tariff rocks in our harbors to limit the inflow of their goods, they will do the same.

But this is just one battle in the Trump administration’s trade war, a campaign that took a serious economy-wide turn at the end of May 2018 when tariffs were imposed on foreign steel and aluminum. Since then, the tit-for-tat process has delivered higher prices to American consumers as well as to international consumers who prefer American goods.

And since then, U.S. farmers have lost partial access to the vast Chinese grain market. U.S. auto producers, who still employ plenty of blue-collar American workers, have lost partial access to the Chinese market for some of their most expensive cars. These folks have been made worse off. Meanwhile, some Americans who have gained protection from foreign competition have been made better off.

Can we estimate the economic effects of all this? Can we accurately identify the winners and losers?

Trade wars have a way of rippling across the entire economy. Their direct and indirect effects are complex and intertwined, and it’s close to impossible to isolate them. The other workings of the economy can confound the problem. Readers of this column know about the uncertainty created by the Federal Reserve’s interest rate changes and the threatened, and then real, government shutdown. There are also “Brexit,” Iran and Venezuela sanctions, and oscillations of the world economy, just to mention a few.

With those limitations in mind, it’s still possible to examine economic pictures, get a feel for what may be happening, and form sharper questions about winners and losers.

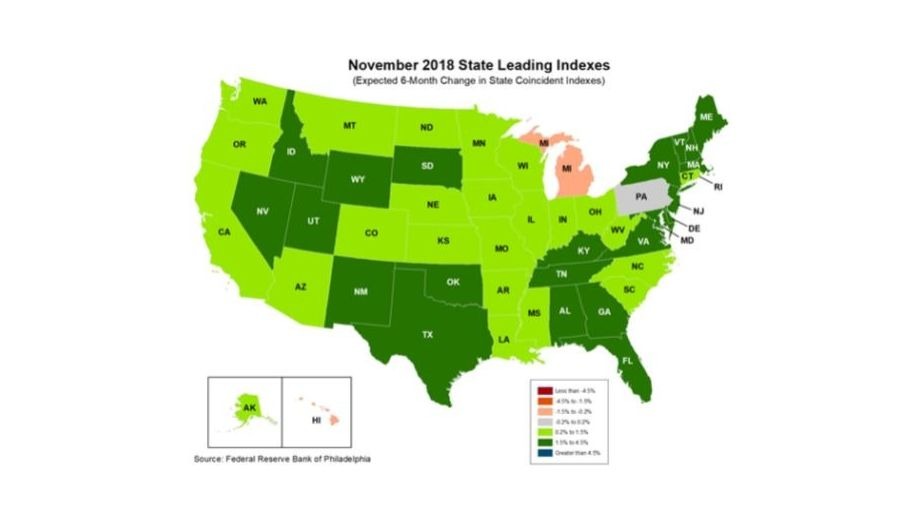

In November, I did just that by showing in this column maps that estimated some future economic prospects for the 50 U.S. states. These leading indicator maps, produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, are based on a multitude of variables that include employment, average hours worked in manufacturing, the unemployment rate, housing permits, unemployment insurance claims, interest rates, and a few others. They look six months out and offer a forecast.

With six months having passed since steel and aluminum tariffs initiated the trade war, it’s time to take another glance.

In the following map for May 2018, the month the tariffs took effect, you’ll notice the prevalence of the dark green, predicted high-growth states. These include heavy manufacturing states North Carolina, South Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The dark green hue also shows up for West Virginia and many of the grain-producing states, such as Illinois, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. There are also two slow-growth states, Kentucky and Maine, and no negative growth states.

Below May’s rendering is the most recent map by the Philadelphia Fed, for November. Notice how things have changed. Prospects have weakened for those four manufacturing states — the Carolinas, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, which now show zero predicted growth. Michigan’s prospects have turned negative, and a handful of grain exporting states have turned light green.

There is little doubt that the prospects for the U.S. economy have weakened since May as we’ve faced a combination of different headwinds. As difficult as determining which factors have done the most damage can be, there is plenty of evidence showing that trade wars are one of the forces eroding people’s prospects across a large number of the 50 states.

Yes, the U.S. economy is on a roll, but the direction is downhill. We will see what the next series of charts tells us. Perhaps the trade negotiators will successfully take some rocks out of our harbors.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner‘s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business and Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.