The leaflets appeared on telephone poles and car windshields in my quiet Washington, D.C., neighborhood on Friday before the three days of protesting that reached its crescendo with Trump’s infamous walk from the White House to St. John’s Episcopal Church. No one saw who put them up — plain pieces of copy paper printed over with simple slogans in bold lettering: “KILLER COPS WILL NOT GO FREE” and “A MAN WAS LYNCHED BY THE POLICE. WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT IT?” Or more to the point: “F— THE POLICE.”

Monday morning, after two days of protests in the city, I decided to go to the White House to see what there was to see. I borrowed my daughter’s camera, a digital Nikon I didn’t know how to use, and fashioned some makeshift press credentials for myself out of an old driver’s license and the perp shot on the ID bracelet they’d attached to me during a brief stay at the D.C. Central Cell years ago for an offense involving alcohol. A Washington police officer I had talked to earlier had advised me to bring my press credentials if I planned to be out after Mayor Muriel Bowser’s 7 p.m. curfew. Of course, they don’t give novelists press credentials.

“I’m a freelancer,” I said. True enough, I’ve published a journalistic piece or two over the years, though mostly book reviews.

The cop looked at me, eyes narrowed: “Then, bring something you wrote for someone,” he said.

So I stuffed one of my novels into my camera bag, along with a bottle of Visine for the tear gas, two bottles of Safeway water, and a rice crispy treat, and laced up my ancient Doc Martens for the hike downtown. It didn’t occur me to question my motives. “A novel is a mirror carried down the road on the back of an ass,” the great French novelist Stendhal once said. “It reflects the mud of the gutter and the blue of the sky above.” Whether I was the mirror or the ass, I wasn’t quite sure.

Late Monday turned beautiful and cool, the fresh air spiced with pepper spray and pot smoke.

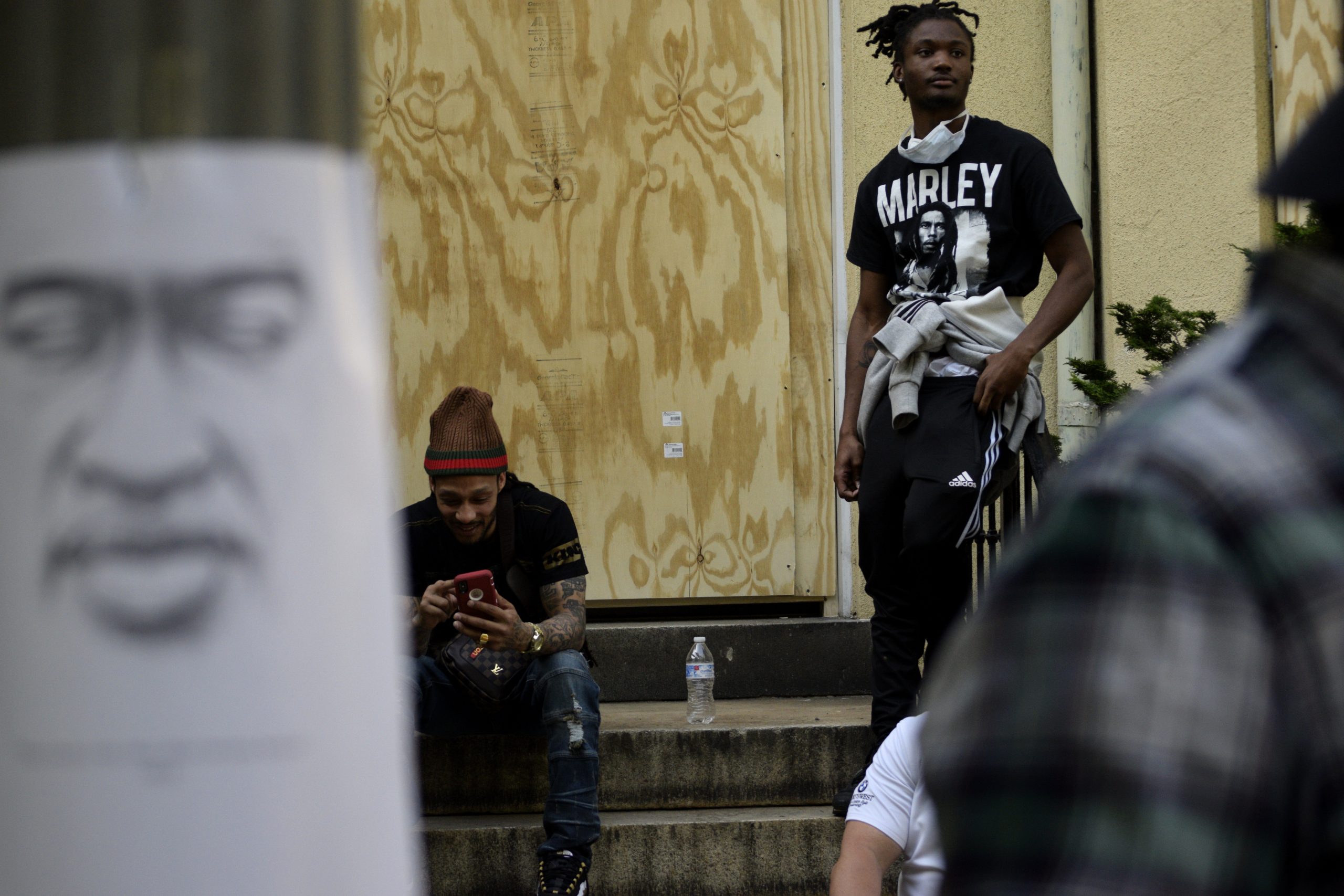

A heartbreaking green-gold light filtered through the chestnuts and oaks of Lafayette Square, now fenced off from several thousand swearing, shouting, reefer-smoking, very angry, young protesters. The average age was about 25, and the crowd was roughly three-quarters white and generally tattooed. The rest were black, some Howard University intellectuals, some from the rough side of town, dreadlocks and tightly muscled bare chests proudly displayed. Then there were the professional agitators — antifa types, anarchists of all races from everywhere, done up in professional-grade gas masks, skateboard helmets, and football pads, looking like Mel Gibson in The Road Warrior. That was the crowd, plus a few of the usual homeless crazies. As I watched, one of the latter began howling and fell to the ground.

I walked around snapping pics whenever I saw a shot, dodging and weaving and trying to act like a real photojournalist. But somehow they weren’t coming out, all over- or underexposed or out of focus. Then, a voice at my shoulder said: “What are you doing here?” It was a friend, a genuine professional photojournalist who regularly sells his excellent shots to the wire services, now on assignment, he told me, for Agence France-Presse. I told him about the mirror thing and the road and the ass. He shook his head, took my camera, adjusted it, handed it back.

“When the flash-bang grenades go off or the tear gas hits, run,” he said.

“Flash-bang grenades?” But he had gone back to work with his telephoto lenses and digital marvels, disappearing into the crowd, and I went back to mirroring the scene with my daughter’s camera, a Christmas present from her mother.

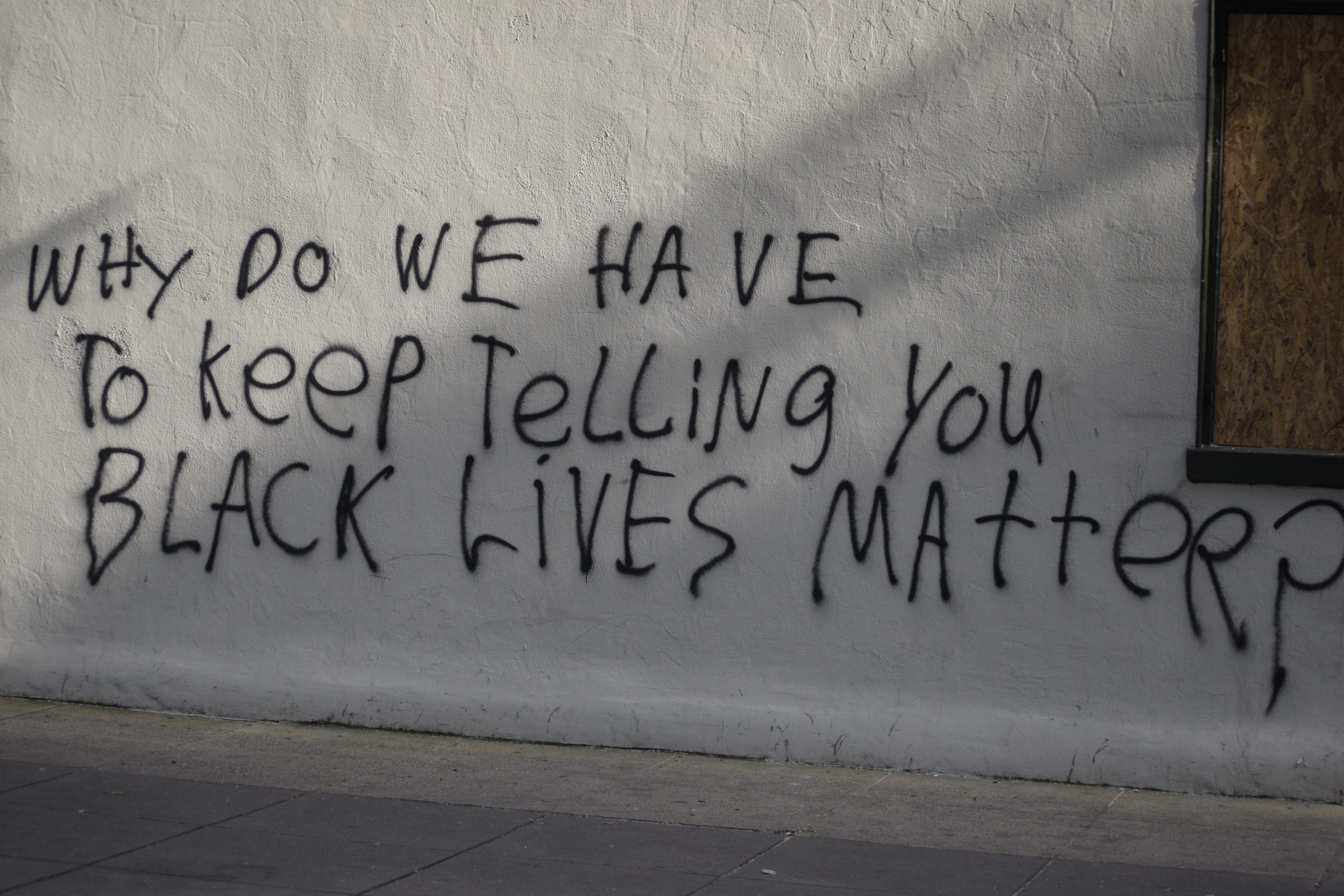

The streets around the White House were now cordoned off by police in riot gear and National Guardsmen in camouflage. The graffiti on the Decatur House declared, “Why do we have to keep telling you black lives matter?” Stephen Decatur, a famous American naval hero whose contemporaries thought him destined for the presidency, once known to every schoolchild, had been tragically killed in a duel in Bladensburg in 1820. No one here today seemed to care about that.

Similar graffiti and the ubiquitous slogan “F— 12” (did the youthful protesters think Trump was our 12th president? No, apparently the 12 refers to the police somehow) had been scrawled on the statues of 18th-century worthies at the corners of the park: Baron von Steuben and Comte de Rochambeau, both foreign aristocrats who had come to help during the revolution, believing this country to be the last, best hope for liberty and freedom for the human race.

On Sunday night, someone with a hacksaw had tried to cut the leg off Andrew Jackson’s horse prancing at the center of the park, and the “peaceful protesters” torched the groundskeeping structure, atop which they postured now in billowing pot smoke clouds. Great mounds of bottled water and snacks (candy bars, bags of Doritos and Cheetos, and cellophane-wrapped turkey-lettuce sandwiches) had been deposited along the sidewalk across the street from the blackened ruins of this structure.

A Secret Service agent told me that they had found stolen cars parked around the city, trunks full of bottles filled with gasoline. The work of outside agitators, he said. A protester insisted this was entirely wrong (in more colorful language), a conspiracy theory put about by the police to justify a harsh crackdown. I didn’t know who to believe. “Some lies reproduce the truth so well it would be an error in judgment not to be deceived by them,” said the worldly French philosopher Francois de La Rochefoucauld.

But, as I watched, a rented van backed up 16th Street and deposited more pallets of water, boxes of plastic eye goggles, hand sanitizer, and, weirdly, gallons of milk, anecdotally thought to ease the sting of tear gas. Who had paid for all this stuff, the posters, the leaflets, the sandwiches, the snacks, the milk, the goggles, and the rented vans?

Green squares of paper instructing the arrested how to act and listing a number for legal aid littered the gutters. A whiff of organized conspiracy seemed to hover with the pot smoke over an otherwise grassroots demonstration. I began to get the feeling that this thing had indeed been planned in advance, long before George Floyd’s cruel and tragic death — and that it had as much to do with what my friend the photojournalist called, dismissively, “election-year politics” as anything else.

Indeed, the chanting of the protesters largely coalesced around injunctions to “FUCK TRUMP!” and for a while, the gathering took on the character of a Democratic campaign rally — before pingponging back to “BLACK LIVES MATTER!” and “F— THE POLICE!” and “GEORGE FLOYD!”

In deference to the pandemic, apparently over now, a masked youth went around spritzing people’s hands with sanitizer: An epidemiologist recently opined in the pages of the New York Times that folks should feel free to go out and protest, just wear face masks while doing so.

After a while, the peaceful crowd began throwing plastic water bottles full of water, rocks, and other projectiles at the police in their riot gear behind the waist-high barricades. Most of these missiles more or less harmlessly impacted the Roman legionnaire shields of the officers. Funny how crowd-control tactics haven’t changed much since the late Roman Empire when Empress Theodora sent the Praetorian Guard into the Hippodrome to quell the Nika rioters. That time, the historian Procopius tells us, 40,000 died.

After a while, my friend the photojournalist called my cell. “Better move back,” he said. “Trump is going to clear the streets around the square, he wants to walk to St. John’s Church for a photo-op.”

“What? How do you know this?”

“I have my sources,” he said mysteriously. “I’m going to my truck to get my Kevlar.”

The mood on H Street had indeed suddenly turned ugly. The protesters began shaking the low fences and shouting more invective and throwing more bottles, this time with a vengeance. One of them caught an officer full force on the shoulder and nearly knocked him down. Suddenly, a troop of mounted Park Police moved down H Street — there’s nothing like horsemen in armor (impressively studded black leather) to scatter a crowd.

Moments later, the barricades opened, and a phalanx of shielded riot-clad police officers moved forward. The crowd shifted back abruptly, then began to run, some of the young women screaming. Flash-bang grenades went off all around. One of them exploded near me, rattling the fillings in my molars.

“What am I doing here?” I thought, desperately. “I should be in the library working on my latest novel” — a period piece safely set in the 18th century. But the libraries are closed now, and I didn’t get a chance to answer this question. A mass of people surged toward the boarded-up husk of the Hay-Adams Hotel, and I ran with them, out of breath, an old fat man with his daughter’s camera, cursing himself for a fool.

Still, I went back the next night and the next, snapping my pics, recording history as I saw it. By Wednesday, the demonstrations had taken on the character of a Lollapalooza concert, with very stoned young people, arms around each other, sitting on the ground, singing, smoking pot, and eating donated sandwiches and chips. Part of these demonstrations was always about people being sick of the lockdown, all the pent-up energy and frustrations of staying in a one-bedroom apartment for three months staring at the inanity streaming on TV. Time for life and rock-throwing and radical politics, pandemic be damned.

Meanwhile, crowds of the hardcore hooligan fringe had moved up Wisconsin Avenue a couple of nights before in defiance of Bowser’s curfew, looting storefronts at Mazza Gallerie in Friendship Heights and into Maryland.

“I hear they broke into Saks,” I heard a middle-class matron say the next day at Trader Joe’s.

“I hope they didn’t hit the makeup counter,” her friend said. Similar women had said similar things when the Communards burned the world’s first department stores in Paris in 1870.

On Thursday morning, with most of the mess over, I went around taking pics of the spray-painted and vandalized monuments. Even Lincoln, enthroned in his beloved memorial, massive as the Hall of the Gods in Valhalla, had not escaped the destructive work of the antifa crowd. At the same time, in Alexandria, the City Council had quietly removed from its roundabout on Washington Street the statue (also much beloved by some) of the lone Confederate soldier lamenting his dead comrades.

It seems both sides had lost the war.

The killing of Floyd was a tragedy of national proportions — international proportions, even. They demonstrated in Copenhagen the other day, where a black person hasn’t been seen in years. But before it’s too late, and everything has been vandalized or destroyed in Floyd’s name by the “bad actors” (as the police call them, those stealthy enemies of the republic Lincoln helped preserve), we should all meditate on the words of Edmund Burke, the 18th-century political philosopher: “Only with infinite caution should we pull down an institution which has served the common purposes of society for generations without a model of proven utility before our eyes.”

Robert Girardi is a novelist and nonfiction writer from Washington, D.C. He can be reached at [email protected].