CLEAR SPRING, Maryland — It’s 7 a.m. at the McDonald’s drive-thru just off U.S. 40 as a cheery, freckle-faced server emerges from the side door to deliver an order to a car pulled up to a parking spot in a waiting area.

“Heeeere’s your Egg McMuffin, young lady,” she announces with a broad smile.

For the next half-hour, a flurry of travelers and regulars grab a quick bite on the run or settle in with friends to trade their thoughts on the Blazers, the local high school football team, and their new coach. The weather and various aches, ailments, and community small talk also fill the fast-food restaurant.

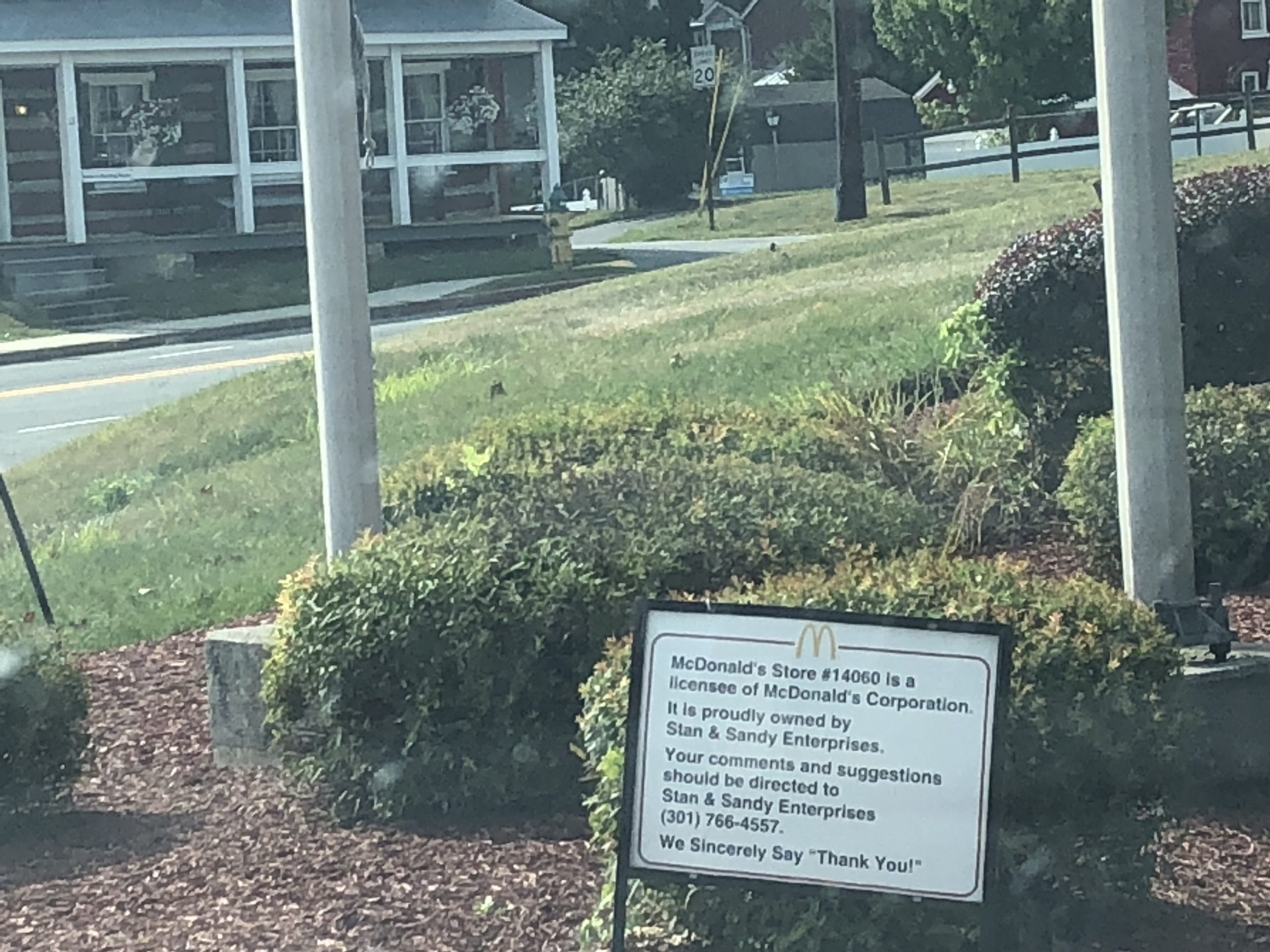

Often, when people think about McDonald’s ownership, they picture a big corporation located miles from their restaurants, with CEOs disconnected from the communities they serve and the people that work for them. But the truth is most of the restaurants that sit under the golden arches are franchises owned by people like Stan Neal, who owns this McDonald’s along with 20 others in Maryland and West Virginia.

Neal got his start as a 15-year-old flipping burgers at a Hagerstown franchise nearby. He has not only stayed rooted to his community, he gives back to it through donations to the local school, scholarship monies, and free meals to the needy. When he owned a motel, he gave out free rooms a few years ago when a historic flood hit the area.

Neal and the thousands of McDonald’s franchise owners across the country are not the kind of big corporate bosses pictured by activists and critics. This complicates the increasingly hysterical and increasingly frequent boycotts of corporations perceived to have violated some woke dogma.

“People want to make a statement by boycotting corporations because of the political views of the ownership,” said Tom Maraffa, professor emeritus at Youngstown State University.

“In the case of fast-food companies, often the local restaurant which would be the subject of the boycott is a franchisee who may have held the franchise years before the current political climate and may even have political views that differ from those corporate leadership,” he added.

Never mind the actual employees.

Last week, it was Olive Garden that was targeted, falsely, as being a corporate supporter of President Trump. Two weeks ago, a boycott was called against Equinox and SoulCycle because owner Stephen Ross was hosting a fundraiser for Trump. Several weeks ago, Nike pulled patriotically inspired shoes with the Betsy Ross flag because brand ambassador Colin Kaepernick objected to the design, causing people on both sides to proclaim their intents to boycott the brand.

It’s all so exhausting.

The outrage mob has become such a parody that stand-up comedian Dave Chappelle took a poke at the culture in his new Netflix special. He did an impersonation and asked the audience to name the target.

“Duh! Hey! Durr! If you do anything wrong in your life, duh, and I find out about it, I’m gonna try to take everything away from you, and I don’t care what I find out. It could be today, tomorrow, 15, 20 years from now, if I find out, you’re f–king, duh, finished!” said Chappelle.

While the audience began yelling it was Trump he was impersonating, Chappelle instead pointed directly at back at them and said, “That’s you! That’s what the audience sounds like to me. That’s why I don’t be coming out and doing comedy all the time, because y’all … is the worst motherf–kers I’ve ever tried to entertain in my f–king life.”

In other words, it is not just corporations who are being boycotted or canceled. It’s individuals who are being canceled by culture and the journalist class. This past week, the Washington Post ran a piece flagrantly smearing author J.D. Vance, taking his laments about falling birthrates in America and absurdly labeling it as white supremacy.

Maraffa argues that however visible this cancel culture and boycott fever are, they have not found their way into American life in a broad and meaningful way. When they do, it often backfires.

Consider the case of Chick-fil-A, when the social justice crowd went into full protest against the Georgia-based company for the faith of its leadership. Despite hundreds of protests, and government bodies in San Antonio and Buffalo, New York, banning their restaurants in their airports, nothing has gotten in the way of Chick-fil-A’s unmatched growth.

Maraffa worries what things would look like, though, if real life did become like Twitter. What if boycott lists were something people carried on their person or in their smartphone?

“It’s not beyond the realm of possibility,” he warns. “Performance wokeness is a plague, and we should do everything we can to avoid it from seeping into our daily lives.”