Occasionally, you’ll see political commentators wrongly say that a presidential nominee isn’t allowed to pick a running mate from his own state. The slightly less wrong error that floats around is that the ticket can both be from one state, but that they’d be giving up their home state’s electoral votes.

These errors are both misreadings of the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, which basically created the system of President-Vice President tickets. Here’s the relevant passage:

Read that again. Now imagine that Jeb Bush wins the presidential nomination, and that he picks Marco Rubio as his running mate. The 12th Amendment doesn’t meaningfully affect electors from 49 states or D.C., but it does restrict what Florida’s electors can do.

Specifically, none of Florida’s 29 electors could cast a Bush-Rubio ballot. This doesn’t mean Bush-Rubio would need to win even without Florida. It does mean winning a close election becomes trickier.

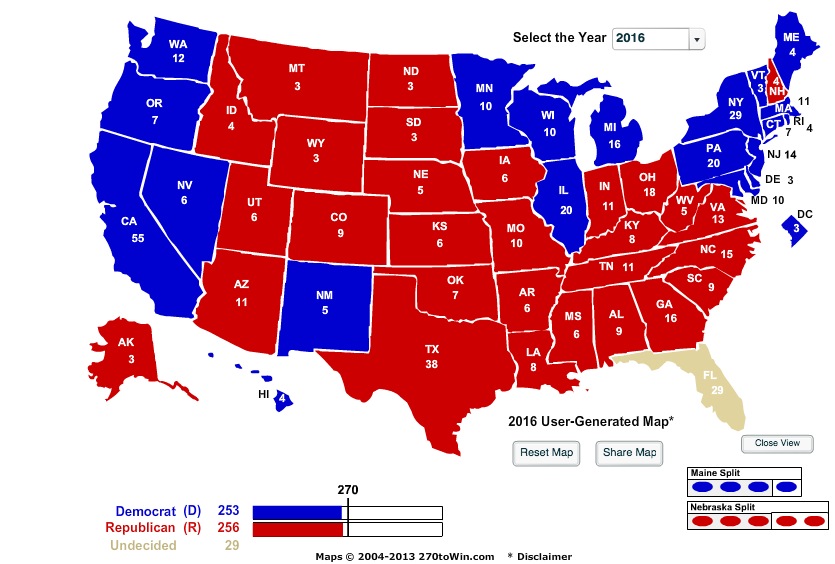

First, imagine Bush-Rubio win what Romney won in 2012 plus the six closest Obama states–Florida, Ohio, New Hampshire, Colorado, Iowa, and Virginia. Normally, that would be enough for 285 electoral votes (270 needed to win). But Florida’s 29 electors are constrained, so, for a second, take them off the scoreboard. Here’s what you’re looking at:

The GOP ticket would have 256 votes pre-Florida. So, 15 of Florida’s electors vote Bush-[BLANK] or Bush-Ryan, it doesn’t matter. the other 14 of Florida’s electors vote [BLANK]-Rubio, or Boehner-Rubio, it doesn’t matter. Bush would walk away with 271 electoral votes for President, and Rubio would have 270 for VP. Victory.

Here’s one way of putting it: A Bush-Rubio ticket would need to “win” 285 electoral votes in order to win in the Electoral College. The generalized way of putting it: if both members of a ticket are from the same state and they win their home state, their Election Day margin of victory must be equal to their state’s electors, divided by two.

For instance, Wisconsin has 10 EVs. A Walker-Ryan ticket would need to get to 275 on Election Day in order to win in the Electoral College.

But here’s the next, even more fun scenario:

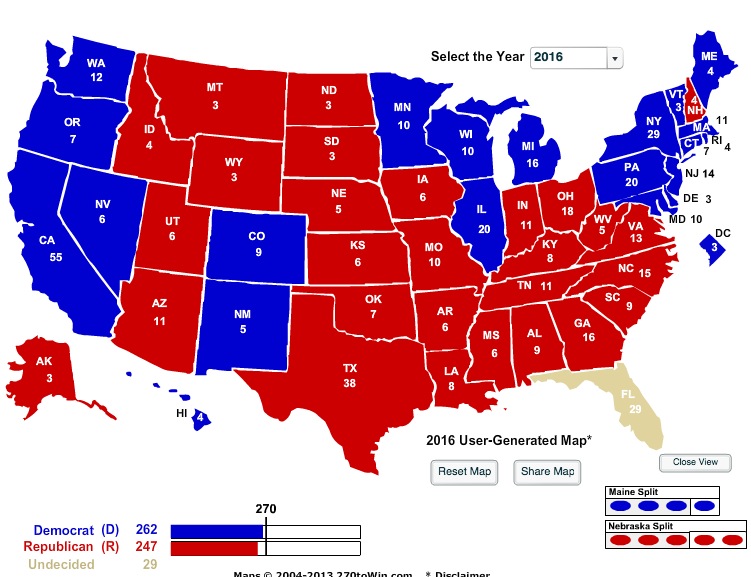

Say Bush-Rubio barely win enough states, including Florida, to get a slim majority of EVs. For instance, in the scenario below, where they don’t carry Colorado. In that case, the electors could push either Bush or Rubio over the finish line, but not both.

You might think, ah well, at least the GOP carries the presidency, if not the vice presidency. But here’s the thing: If nobody gets a majority in the Electoral College, for either President or VP, the election goes to Congress — but a different chamber for a different race. If the Electoral College doesn’t pick a President, the House of Representatives chooses among the three top vote-getters, in a vote in which each state’s House delegation gets one vote. For VP, the Senate would choose, in a straight-up vote, among the top two vote-getters.

So, in the 2016 scenario I outlined above, the right play might be for Florida’s electors to vote [BLANK]-Rubio. Here’s why: Congress counts the electors after the new Congress is sworn in. The 2016 elections are likely to give Democrats a majority in the Senate (especially if Rubio isn’t running for re-election). But Republicans would probably hold a majority of state delegations in the House.

So, in the second scenario above, Rubio wins the VP slot in the Electoral College, and the Presidential race goes to the House, where Bush defeats the Democrat.

This has been your probably-not-useful-but-maybe-interesting constitutional lesson for the morning. Carry on.