PITTSBURGH — A little more than 75 years ago, my father and a handful of friends, all sons of Italian immigrants, hitched up their sleds and rode them from the top of the city of Pittsburgh’s Summer Hill neighborhood slopes onto East Street during what was later called the Great Appalachian Storm. That superstorm on the Thanksgiving weekend of 1950 was one for the books, causing tremendous suffering and hardship. But it brought out the best in humanity, too.

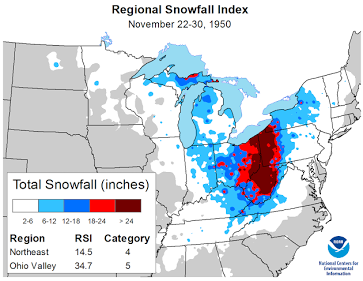

The Category 5 storm was slow-moving, battering the lower Appalachian mountains, the Ohio Valley, the Great Lakes, and the entire Northeast with staggering snow totals that still hold the record today.

According to the Weather Channel, tiny places such as Corburn Creek, West Virginia, received over 63 inches of snow. In Pittsburgh, there was more than 30 inches, and just across the state lines of West Virginia and Pennsylvania, in the town of Steubenville, there was over 44 inches. The National Centers for Environmental Information ranked this as the most extreme winter storm on record for the Ohio Valley. The frigid cold stretched from New York City diagonally into the Appalachian region, where temperatures dropped to an arctic 1 degree Fahrenheit in Asheville, North Carolina, and Georgia.

There were tragedies that emerged from that storm, ranging from fires in homes that firefighters were unable to reach to instances of exposure and flooding. In total, the United Press International estimated that as many as 212 people lost their lives. Lawlessness was even reported in Cleveland, Ohio, and a “shoot to kill” order was issued to “any prowlers caught breaking into abandoned businesses and homes.”

Life was upended in other ways, too.

The storm was so severe that, according to the Pittsburgh Sun Telegraph, where my grandfather worked at the time, the annual backyard brawl, the Pitt-Penn State football game, was postponed for the first time since the rivalry began in 1893. It was supposed to be the golden anniversary edition of the traditional season-closing game. But Pitt officials finally threw in the shovel and rescheduled for the next day. Pitt’s stadium turf was covered with more than 100,000 cubic feet of snow.

Allegheny County Judge William McNaugher closed all sessions of court because of the storm. The IRS shuttered all offices in the Western Pennsylvania region. That bank holiday brought a run on cash at hotels and restaurants.

In Pittsburgh, the Sun Telegraph noted that city police maintained a crew to handle any acts of violence or looting. But little crime was reported. Police were on call, however, for expectant mothers. During the storm, they received 30 maternity calls. Working with the U.S. Army, they were able to handle all but two. Those two mothers had the babies at home.

There were stories of cab companies working diligently to get people to and from wherever they needed to go. The only food shortage noted in Pittsburgh was milk, and local dairies rallied to drive their trucks to various neighborhoods for parents who needed it for their children.

Mayor David L. Lawrence, later Pennsylvania’s governor, put out a call for all Pittsburghers to help out by clearing the streets in front of their homes. The mayor warned everyone to stay away from downtown. All social functions were canceled.

Hundreds of extra laborers and volunteers from the local steel mills were asked to man snow-lifting equipment in the city. Army tanks even rumbled over snow-packed side streets, compressing the flakes so the streets would be open for firetrucks or ambulances. Trolley service runs were erratic at best. And department stores were closed.

Most of the stories in newspaper archives tell a story of communities pulling together to help each other out. Neighbors checked in on each other, often sharing leftover Thanksgiving turkey and stuffing.

And today, despite what you see on social media, we aren’t much different from our forefathers. A recent trip to several local grocery stores showed long lines but also unity and purpose, and a sense that we are all in this together.

Eileen Cunningham, who lives in the Lincoln Place neighborhood of Pittsburgh, didn’t have time to shop before Friday. She had been on grandma duty for four days after her daughter recently gave birth.

Eileen said that when she pulled up to the Aldi’s in West Mifflin, she had expected a long line. But she didn’t expect to see how well people were handling the situation or the camaraderie that they shared while waiting their turn at the cashier.

The line at Sam’s Club dwarfed what the mother of four experienced at Aldi’s. Yet she found the same sense of “in it together” that she found at the other store.

“Well, Sam’s Club was a zoo. However, everybody in line is more anticipatory, and nobody’s huffing and puffing there. It is actually different than a regular day, whenever people are usually kind of miserable and on their way,” she said, laughing. “I think everybody knows this is something different, and they are respecting that we are trying to prepare for something big,” she said.

Sam’s Club’s lines were very long, but despite having never met, people were often laughing and chatting back and forth. Cunningham laughed as one man said, “I think we should go home because the snow’s going to come before we get out of the store.” She had a bunch of popcorn in her cart, to which another woman behind her remarked about respecting her affection for the snack.

“Normally, people don’t say anything. But today was very different, and it’s kind of funny because it didn’t make the wait so long; everybody was talking to each other,” Cunningham explained.

Nearly everyone in line asked the cashiers what it was like, and the cashiers kept saying the same thing: “It makes the day go by quickly, and everyone is happy to be here because they are not in the storm yet.”

SALENA ZITO: PENNSYLVANIA DAIRY FARMERS CELEBRATE THE WHOLE MILK ACT

Even on X, some of the posts were comical as people went back and forth about whether the storm would be a dud, how they might be disappointed if it was, and if Secretary of State Marco Rubio would be named snow czar — a joke about the ever-increasing number of jobs President Donald Trump gives him.

The possibility of the strains on the infrastructure is certainly real. Ditto for hazardous driving, flooding, downed power lines, and the danger of electricity for days should not be diminished. Yet, you don’t have to look hard to find that the fabric of coming together in our country is still alive and well and flourishing.