Sometimes, a public issue takes on a particularly personal importance. Such is the case for me with regard to the woke leftist takeover of James Madison’s Montpelier estate, as discussed in a column yesterday.

Please forgive the quasi-solipsism of the following account, but it’s the only way I know to explain why the assault on Madison’s memory seems like a personal affront as well as an objectively disordered approach to history. Sometimes, something personal can resonate with readers.

On James Madison’s March 16 birthday in 2000, Investor’s Business Daily published a column of mine noting that one year from that day would be Madison’s 250th birthday. I opined that Congress should appoint a commission of scholars (unpaid) to help commemorate the 250th and use it as an occasion for civic education. I said the commission should sponsor or encourage high school essay contests about the Constitution, that the scholars should meet together at least once, and a few other things.

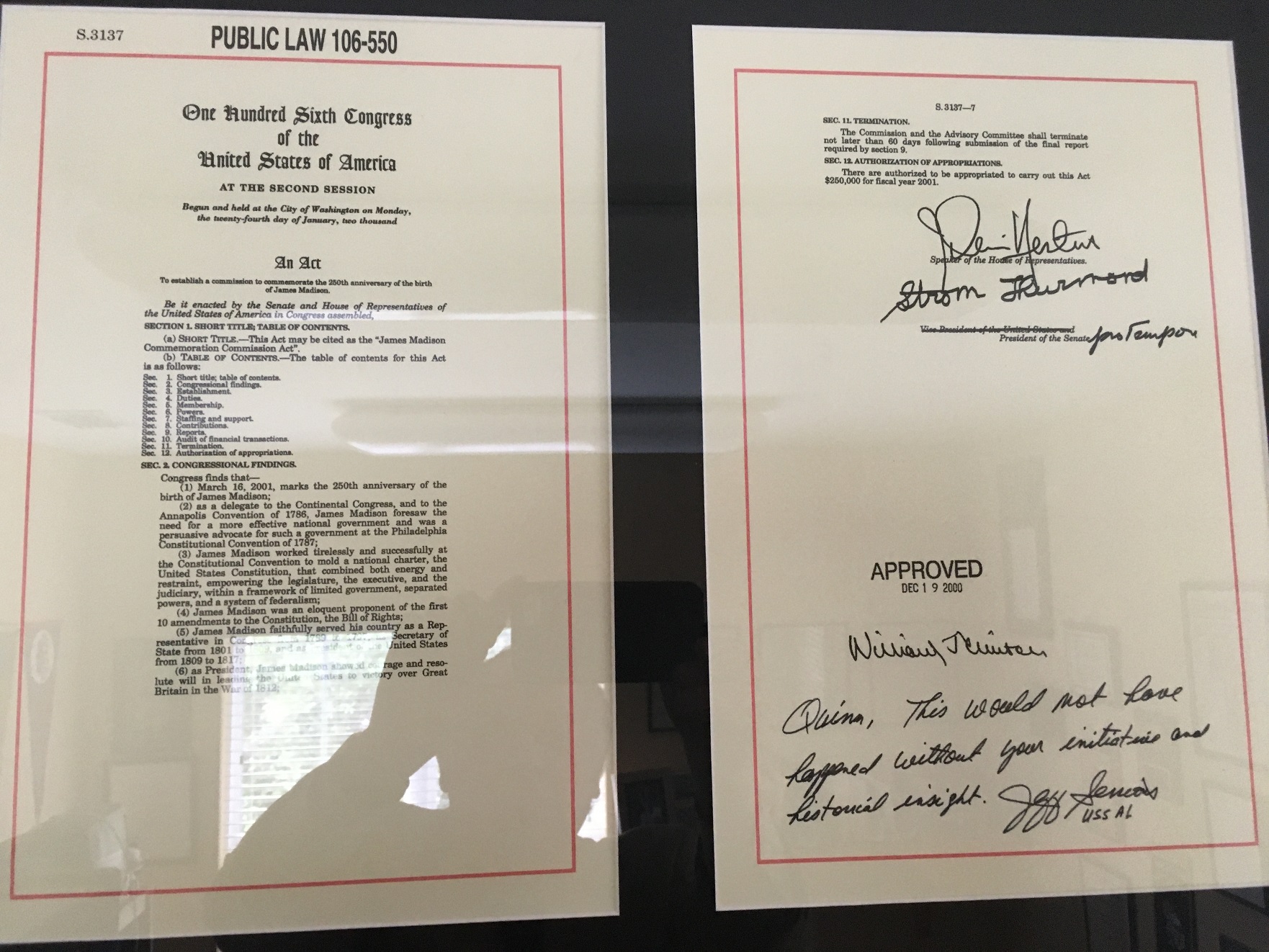

Then-Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-AL) saw my column and turned it into a bill directly tracking the column’s suggestions. It was one of the final bills passed and signed into law in the last Congress of President Bill Clinton’s tenure. Sessions gave me the original, official “Redline” copy of the bill signed by Clinton, Speaker Dennis Hastert, and Senate President Pro Tem Strom Thurmond.

The scholars were appointed; they held a symposium in an ornate room in the Library of Congress on March 16, 2001, with me as the only reporter present for the private part of the session; and they promulgated a call for civic education. There was a grand dinner that night at a banquet hall in the Library of Congress honoring Madison, with Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Sessions presiding and Justice Antonin Scalia among the numerous public officials in attendance. By happenstance, I rode the elevator with Scalia, but I couldn’t think of anything intelligent to say.

For me, it capped a day in which I had driven the 95 miles out to Montpelier, then only in the early phases of its restoration from what the DuPont family had done to alter it radically, and I enjoyed a fascinating private tour of all they were planning. The curators said the law creating the commission and the commemoration had hugely helped draw attention to Montpelier’s mission of celebrating the life and thought of the Father of the Constitution.

Several years later, halfway through the restoration, I was graced with another private tour. About five years after that, with the restoration almost complete, I took a public tour. By then, the foundation was well into its efforts to excavate evidence of the lives of the slaves who lived there. In context, that undertaking was appropriate and wise. Little did I know that almost all context would be thrown aside, with slavery essentially becoming Montpelier’s predominant focus.

The original mission of Montpelier obviously is something I feel personally invested in — and therefore personally upset at what has happened to it. Without Madison’s genius and unflagging determination, there is no way the U.S. Constitution would have been written and ratified. Without Madison’s work beginning in the Virginia colonial legislature and culminating in the new nation’s first Congress, there is no way the U.S. principles of religious liberty would be as well-protected.

James Madison is and always should be a Hero of Liberty, capitalized and bolded. And in 2051, 2101, and for as long as the United States survives, his example should be celebrated and emulated.