In an ironic turn of events, the day after President Trump shocked the world with his plan to impose border taxes on all imports from Mexico beginning June 10, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia released its latest 50-state “leading indicators” map, which forecasts a data-driven look at state economies six months in the future. The “Tariff Man,” as the president has styled himself, is once again living up to the moniker.

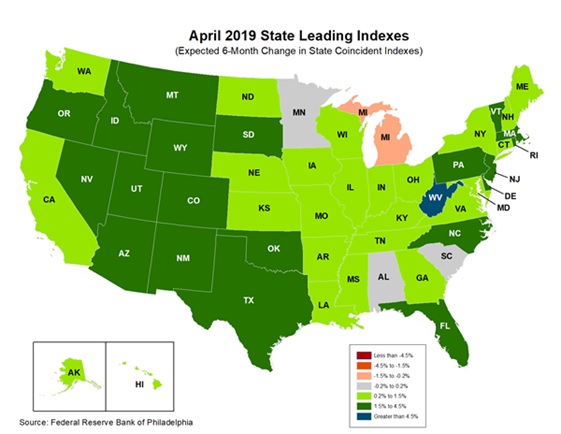

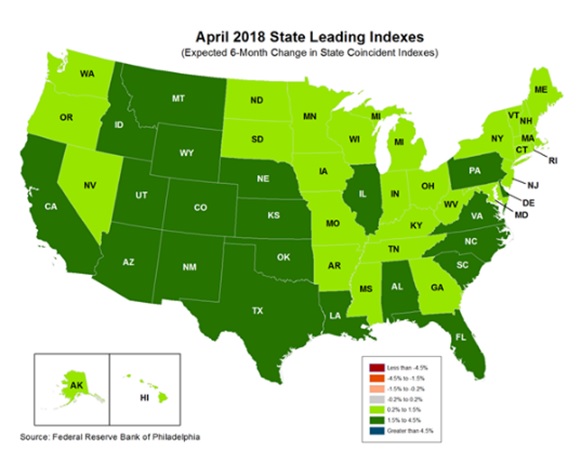

I provide here the latest Fed-produced map, along with its April 2018 counterpart for comparison purposes. The April 2019 map forecasts state economic conditions for October 2019, about four months before the Iowa presidential caucuses.

Here we see Michigan headed toward negative growth and two other leading auto-manufacturing states (Alabama and South Carolina) pointed toward the same destination. With the exception of West Virginia, the indicators are not bright east of the Mississippi River.

How does this relate to Mexico, tariffs, and the U.S. political landscape? Mexico is, as we all know, a top U.S. trading partner. It ranks number one in the most recent quarter and is a major source of automobiles, trucks, and vehicle parts imported to U.S. markets. Of course, this is why Trump can expect a meaningful Mexican reaction to his Tariff Man action.

On the other hand, Trump had to know that his announcement would impose high costs on the U.S. auto industry and American consumers. But having weighed the political importance of forcing Mexico to do more about the movement of U.S. asylum seekers, he took the action nonetheless.

There is no denying that the United States faces a messy situation on its southern border, one that our politicians have refused to fully deal with across recent decades. It is just as obvious that prospering, amicable neighbors are better situated to deal with tough problems than two countries engaged in a contentious trade war. One might reasonably think our leaders could organize a joint U.S.-Mexico effort to bring order and stability to the border. It’s conceivable that soft diplomacy, unlike trade war bluster, could generate a win-win outcome that would make all parties better off.

Similarly, reasonable people could be forgiven for thinking that politicians seeking reelection in 2020 might be a bit cautious about deliberately forcing an economic slowdown on vast and identifiable areas of the nation they hope to lead. But Trump, having brought prosperity-enhancing tax reductions and regulatory reform, seems willing to trade some of the gains for yet another day as a Tariff Man. Indeed, he seems to enjoy making the trade-off.

How much prosperity might we be giving up? Compare the two maps and notice how far the prospects of 50 states have regressed in the past year. As always, note the number of green states (many of which now have a softer hue) and the number of gray and pink states, which reflect very weak or negative growth prospects. In 2018, there were no pink or gray states. In 2019, there are four. The nation’s economic complexion changed across those 12 months but not for the better.

It is worth pointing out this most recent map does point to slightly better times than those from February and March. But the just-arrived May IHS Markit Manufacturers Index for the United States cut heavily in the direction of a slowdown, coming in at its lowest level since 2009.

Even so, the conclusion is the same: If carried out as promised, tariffs imposed on U.S.-bound Mexican exports will impose costs on U.S producers and consumers — especially on states that are auto-specialized.

President Trump has chosen to take an unusually risky action, both for the economy he seeks to serve and, perhaps, for himself.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business & Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.