Anecdotal arguments about the state of the economy are not always terribly valuable. Much less so when they suggest the exact opposite of what they are supposed to demonstrate. For example:

When I was a kid, ppl in Texas who lived in mansions were world famous. Now theyre just dentists, insurance agents, etc. The rich get richer

— Kurt Eichenwald (@kurteichenwald) December 28, 2016

Kurt Eichenwald, a Newsweek and Vanity Fair writer who has recently attained some notoriety for — well, it’s really not worth explaining here — is presenting evidence for the opposite case of the one he’s making.

There is plenty of data to suggest that the richest Americans have, on the whole, gotten richer in the time since Eichenwald was a child. But the fact that mere members of the professional class (dentists, insurance brokers) are now living in the sort of homes that were once reserved only for people of great wealth (oil magnates, movie stars, etc.) is really an indicator that the middle class has gotten richer, not that the rich have gotten richer.

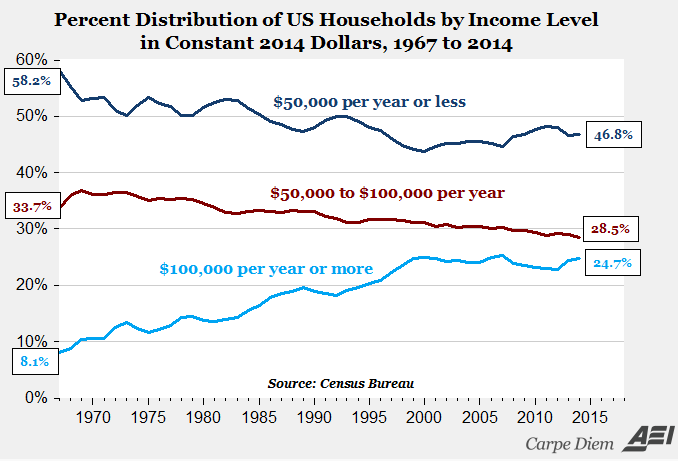

There is data to bear this out, too, at least in terms of income. A year ago, the American Enterprise Institute’s Mark Perry used U.S. Census numbers to show that the share of American households with six-figure incomes (measured in 2014 dollars to adjust for inflation) has more than tripled over the last 50 years.

Over the same period, the long-term trend has been one of modest decline in the share of households in what most people would consider to be a middle-income band ($50,000 to $99,999 per year) and about a 20 percent reduction in the share of households making less than $50,000 in 2014 dollars.

It’s certainly possible to argue that this isn’t happening fast enough, or to point out that this trend has been stalled for more than a decade now, or to present separate evidence that points to measures of growing income inequality. But the long-term trend that Eichenwald’s anecdote illustrates is not one of growing inequality. It is the trend of an increasing and increasingly shared level of basic prosperity that is not necessarily inconsistent with growing inequality.