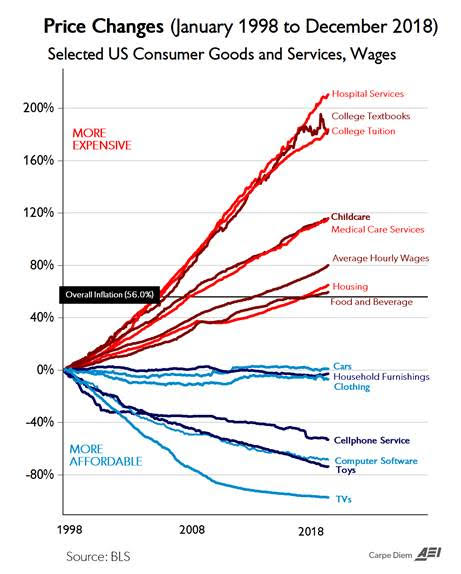

American Enterprise Institute economist Mark J. Perry is highly and justifiably respected for his ability to convey complicated economic relationships by way of rather simple charts and graphs. The most famous example of this, shown here, is called by some the “chart of the century.” The high praise comes about because the chart is loaded with information regarding the types of challenges faced by the Fed and other Washington policymakers. Perry’s most recent version reports price increases from 1998 through 2018 for 14 categories of goods and services along with the average wage and overall Consumer Price Index.

Overall, the result we see is astounding. In a word, the price increases shown for hospital services, college textbooks, and college tuition are startling. Meanwhile, the zero price increases and decreases reported for cars, household furnishings, and clothing offer some comfort.

A quick inspection of the chart raises several observations.

First off, the activities heavily affected by government rules and subsidies are prone to be less efficient and therefore more costly. Hospital services, medical care, and housing fall into this category.

Second, international competition matters a lot. Services and homebuilding are almost immune to global competition. Goods are not. This logic helps explain the taming of costs for TV sets, toys, cellphone services (which include the phone itself), clothing, cars, and household furnishings.

But the exploding costs associated with college tuition and textbooks raise other questions. Yes, there is a lot of government regulation and public sector ownership that affects college operations. And yes, there is an absence of meaningful international competition in the higher education marketplace. But textbooks? What’s happening here?

Perhaps, just perhaps, these two higher education items are plagued by a third consideration that could also affect each of the other 12 consumption categories. Tracking costs across time requires the analyst to adjust for changes in the quality of the goods themselves. For example, how do more efficient engines, additional safety devices, and standard navigation tools affect the value of vehicles over time? Adjusting for such changes so that the cost of a basic automobile can be tracked presents a monumental challenge for the Bureau of Labor Statistics analysts who maintain the chart’s underlying data.

Think about it this way: Just what is included in 1998 college tuition? Is it the same in 2018? What about expanded computer centers, 24/7 information services (libraries!), or more-advanced technology, physics and manufacturing labs? What about the skills of the faculty required to teach and guide research? Have those changed? Did 1998 textbooks include complete online instruction capabilities? Self-contained lectures? They can now.

One can raise similar questions about hospital services. It could well be that higher costs are driven partly by a fourth consideration: When a service is paid for by a third party, there is little incentive for buyer and provider to keep costs low. This implies that government-funded healthcare, higher education, textbooks, and childcare services are especially vulnerable.

I find myself thankful for international competition and hope that we American consumers will get more of it. I also hope the future will facilitate more global competition in healthcare services. And finally, I wonder what will happen to the hidden cost of college tuition and textbooks if some leading politicians get their way and college becomes “free.”

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business and Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.