By the time politicians put their hand on the Bible to take the oath of office, many have made their deals with devil. The current partisan church split in the House of Representatives then provides a decent opportunity to re-evaluate the office and the purpose of congressional chaplains.

Personal salvation cannot be the chaplain’s only goal. Public sanctification through moral direction of lawmakers ought to be the object and religious pluralism, the method instead. In short, it’s time to flood the zone.

In the beginning of the United States, there were constitutionally-mandated chaplains, one for the House and another for the Senate. They are elected at the beginning of each session and are entrusted with offering prayers at the start of the legislative day while ministering throughout Capitol Hill.

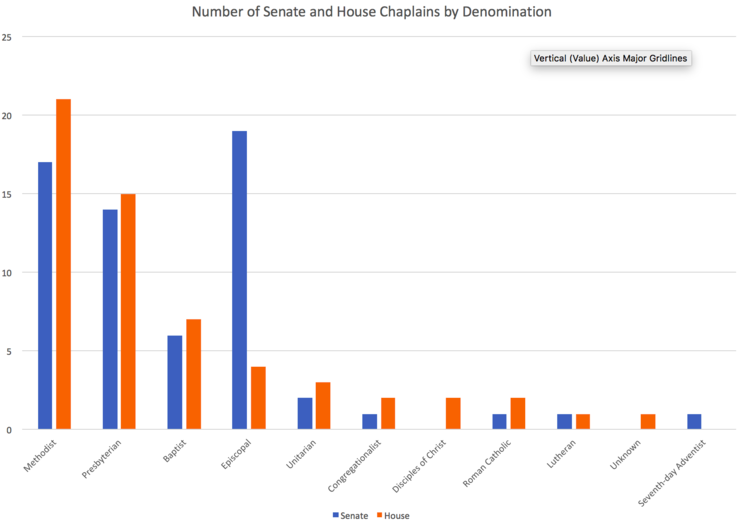

Paul Winfree notes over at N58 Policy Research that since the first Congress most have either been Methodist or Episcopalian. Only a handful have been Catholic and that’s the cause of the current controversy.

Speaker Paul Ryan asked for the resignation of Father Pat Conroy after that priest got political during a prayer. A lifelong Catholic, Ryan was attacked as anti-Catholic. Republican Study Committee Chairman Mark Walker suggested that Conroy’s replacement should be a married man to better understand the challenges of living and working away from home. An ordained Southern Baptist minister, Walker was also attacked as anti-Catholic and resigned from the search committee looking for the next chaplain.

While neither attack on Ryan or Walker has merit, they underscore an interesting point. How can one minister meet the needs of 435 members of Congress? It’s impossible. and that’s the point.

Due to their proximity to power and money, politicians are particularly susceptible to damnation and the rest of us have to pay for their sins (sometimes quite literally). Inside the halls of Congress then, doctrinal disagreements are less significant. Moral brute force is necessary.

Winfree imagines an inter-faith council of several spiritual advisors of all sorts of religious stripes. All those traditions, teachings, and truth claims have the makings of a miniature holy war or at least some nasty interdenominational debates. But here C.S. Lewis, that Anglican beloved by evangelicals and Catholics alike, is helpful:

Lewis continues by observing that while there have been differences between moralities there has never been a completely different morality. No mainstream religion, for instance, celebrates cowardice, dishonesty, or selfishness for their own sake. There are certain things that are right and wrong across all traditions and religions.

When a priest, a rabbi, and a pastor walk in Congress then, they will inevitably bicker about doctrine. They will not, however, disagree on whether it is right or wrong to steal taxpayer money, to cheat on a spouse, or to betray responsibility.

So draft another Catholic priest. Hell, draft a few of them. Hire pastors and padres and preachers from all sorts of denominations. Make certain no congressman can escape a chaplain before leaving Washington. His salvation isn’t necessary, though it’s preferable. General moral instruction at the most basic level is necessary. A low bar outside the Beltway, that moral direction is desperately needed here.