Boeing would easily survive the death of the Export-Import Bank, despite dire warnings from defenders of the taxpayer-backed financier.

By late August, Boeing was already enjoying the largest backlog of orders in the history of aviation. Then on Monday, Irish carrier Ryanair announced an order of 100 Boeing 737s.

It is hard to justify government involvement in foreign purchases from Boeing when private sources of financing have never been more plentiful.

So why are people fretting about the company? Boeing is the most important customer of Ex-Im. In fiscal 2012, 82 percent of Ex-Im’s loan guarantees subsidized Boeing exports. “Boeing’s Bank,” is the derogatory name for the agency. This isn’t a point a pride for the Obama administration or Ex-Im officials, who instead pretend Ex-Im mostly subsidizes small business (less than 20 percent of Ex-Im’s subsidy dollars go to businesses with fewer than 500 employees).

But in some provinces of American politics — mostly the American Right and Washington state—the leading defense of Ex-Im is that we need it in order to save Boeing.

“I want to make the point that those of you who are aggressively seeking reforms, which may or may not enable the continued existence of Ex-Im in any kind of a meaningful way, are playing with fire,” Democratic Congressman Denny Heck of Washington warned in a hearing this summer.

The danger, according to Heck: if Congress pared back Ex-Im subsidies, “we could wake up in 20 years and still have a duopoly in terms of airplane production in this world, but unfortunately it would be Airbus and the state of China and their C919.”

Hawkish conservative Frank Gaffney sounds a similar warning about the aerospace industry. Without Ex-Im, Gaffney wrote, “we are going to find ourselves even less capable of reconstituting our military production lines when, not if, they are needed.”

Heck’s and Gaffney’s arguments boil down to this: We need Ex-Im to subsidize our military-industrial complex so that it’s there to keep us safe. This argument amounts to defending Ex-Im as a double-secret defense budget.

The central premise to this argument, however, is false. A world without Ex-Im is not a world without Boeing. If Ex-Im disappeared tomorrow, Boeing would be fine.

Boeing makes the best airplanes in the world. That’s not really up for debate. Boeing is better than European competitor Airbus, and not because the U.S. government supports Boeing more — it doesn’t. Airbus, on the other hand, is so heavily subsidized that it’s practically a government agency. If anything, the evidence there suggests that intense government support dampens ingenuity.

Whenever government pulls away a subsidy, there is some pain in the transition. Boeing’s record back-order makes this moment the perfect time to transition Boeing out of export subsidies.

About 15 percent of Boeing sales get Ex-Im financing. That’s a big chunk, but those sales wouldn’t disappear if Ex-Im weren’t around. Goldman Sachs, in a recent research note, wrote: “If the US Export-Import charter is not renewed, we believe the overall impact in the near-to-medium term would be fairly limited given the robust financing environment at present….”

The Goldman note added: “It would only require a small step up from each of the many other sources of financing to fill an Ex-Im gap…. a marginal impact to an otherwise very strong existing backlog and ongoing order trends.”

This also tracks with Boeing’s own analysis of the aircraft finance market. The Wall Street Journal reported in 2013 that Kostya Zolotusky, managing director at Boeing Capital, “said he was confident the company could find alternative funding sources for customers that wouldn’t require it to boost its support of aircraft sales.”

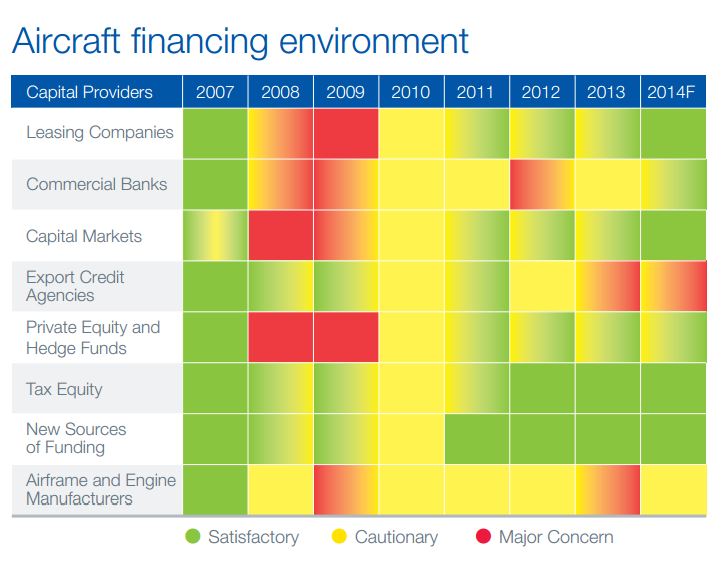

Boeing Capital analyzed the credit market for aircraft last December, color-coding the various avenues of financing based on their health and availability. For 2014, Boeing forecast that leasing companies, commercial banks, capital markets, private equity and hedge funds, tax equity and “new sources of funding” would all be green. In yellow was “Airframe and Engine Manufacturers.” The only category in red is “Export Credit Agencies” — that is, Ex-Im.

“Emirates, Dubai’s flagship airline,” Reuters reported this week, “would not have trouble buying planes from Boeing Co. even if the U.S. Congress fails to renew the U.S. Export-Import Bank’s charter later this month, a senior company executive said on Friday.”

Another important factor: many of Boeing’s customers are owned by governments. Ex-Im approved $40.5 billion in guarantees to airlines from 2007-2014. More than $19.5 billion of this (48%) went to government-owned airlines like Air China.

Boeing officials tell me that they need Ex-Im for when credit markets turn down again, and in order to sell to developing markets. Also, they point to Airbus’s subsidies. “Without Ex-Im, U.S. commercial aerospace manufacturing will shrink,” a Boeing official emailed me.

No doubt a reduction in aircraft export subsidies would reduce aircraft export sales. But cuts to the subsidies will mostly cut into profits made by the foreign airlines who enjoy their Boeings subsidized by U.S. taxpayers, the U.S. banks whose loans are backed by Ex-Im guarantees, and a little bit into Boeing’s profits. That a successful company would suffer slightly from reduced taxpayer subsidies is not a strong argument for continuing the subsidies.

America is lucky to have a company like Boeing. And even in a world where Europe and China slather subsidies on their jet-makers, Boeing is strong enough to survive without financing from the taxpayer.

Timothy P. Carney, The Washington Examiner’s senior political columnist, can be contacted at [email protected]. His column appears Sunday and Wednesday on washingtonexaminer.com.