Here are some further observations about the British election, based on further analysis over the weekend.

3. How did the Conservatives win so many marginal seats (continued)?

In my earlier blogpost I wrote “a look at the election returns as they came in has convinced me (though I am open to persuasion based on a closer review of the numbers) that United Kingdom Independence Party numbers held up well in safe Labour and perhaps safe Conservative districts, but tended to go over to Conservatives in marginal seats.”

I’ve now gone over the numbers and have become convinced I was wrong. My analysis is confined to England and Wales, since Northern Ireland has its own parties and the Scottish Nationalists won 56 of the 59 seats in Scotland, leaving one each for Labour, Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. What I found was that in seriously contested seats, Ukip’s average performance was almost exactly the same as in the United Kingdom as a whole, as was the Labour percentage. On the other hand, the Conservative and Lib Dem averages were significantly higher in contested seats than in the United Kingdom as a whole (though the Conservative percentage was about equal to their percentage in England and Wales).

I treat as “seriously contested” 123 districts identified by the UK Polling Report as electoral battlegrounds, plus six Labour-held seats not on their list, which were won by Conservatives (Bolton West, Vale of Clwyd, Plymouth Moor View, Derby North, Telford and Morley & Outwood, which saw the biggest upset of the night, the defeat of shadow chancellor Ed Balls). UK Polling Report’s selection of electoral battlegrounds was based on the pre-election polling, which of course proved to be wrong; you can see the projections for each seat in the UK on the Electoral Forecast website.

The projections were that of these 129 seats, Conservatives would win 48, Labour 53, Lib Dems 27 and Ukip 1 (the seat of the former Conservative MP Douglas Carswell, who resigned his seat after switching parties and won it in a by-election). The actual results were very different: Conservatives won 99 of these seats, Labour 22, Lib Dems 7 and Ukip the correctly predicted 1. If the projections based on pre-election polling were right, Conservatives would have won 280 seats, Labour 261, Lib Dems 27 and Ukip 1. The actual count was Conservatives an absolute majority of 331, Labour 232, Lib Dems 7 and Ukip 1. The results in these 129 seats taken together made the difference between a governing majority and a hung parliament, in which neither of the major parties, even with its obvious coalition partner (Lib Dems for Conservatives, Scot Nats for Labour, though explicitly), would have had a majority of 323 (the speaker and the four Northern Irish Sinn Fein members don’t vote for parties). A big, big difference.

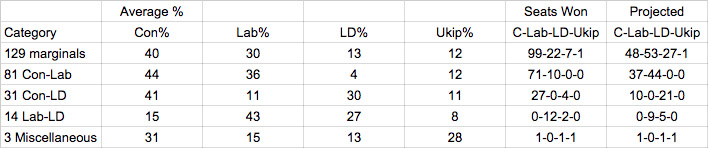

I calculated the average percentage for each party in these 129 seats. The numbers, shown in the table below are not very revealing. Conservatives got more of the votes on average, a margin of 40 to 30 percent over Labour, with Lib Dems at 13 percent and Ukip at 12 percent.

To see what was happening, I disaggregated the numbers by the nature of the competition, showing the average party percentage in each, in the 81 seats where the real competition was between Conservatives and Labour, the 31 seats where the competition was between Conservatives and Lib Dems, the 14 seats where the real competition was between Labour and Lib Dems and three miscellaneous seats (Clacton and Rochester & Stroud were Conservative-Ukip contests and Ceredigion is a Welsh seat where the competition was between Lib Dems and Plaid Cymru). The table shows the average vote for the four parties (Plaid Cymru lost, and I’m leaving it out) in all 129 districts and in each of the four categories. It also shows the number of seats each party won in each category and the number it was projected to win.

The overall take is that the Lib Dem vote basically collapsed (remember that they won 23 percent of the national vote in 2010), leaving all but a few of its incumbents losing and leaving it basically irrelevant in Conservative-Labour contests, with a pitiful 4 percent average vote. Labour whalloped Lib Dems by an average of 16 points in 14 Lab-LD seats, all of them held by Lib Dems going into the election. But they outperformed projections only a bit, winning 12 of those 14 seats rather than 9. Not a big pickup. Conservatives had a slightly smaller popular vote margin over Lib Dems, 11 points, in the Con-LD districts, but there were 31 of them, and instead of winning 10 as projected they won 27. In other words, Labour beat projections by three seats, Conservatives by 17.

This is a clue, I think, to what was happening in the Con-Lab seats. The Conservatives ruthlessly targeted their five-year coalition partners the Lib Dems, and David Cameron crowed on the morning after the election that Conservatives had wiped them out in the southwest, from Kingston and Twickenham in southwest London to St. Ives at the southwest tip of the island of Great Britain. Lib Dem voters in the greater southwest have been more culturally liberal, more green on the environment, more supportive of the European Union and more dovish on foreign policy than traditional Margaret Thatcher Conservatives. Cameron has propitiated them in various ways: by supporting same-sex marriage, by planting windmills across the landscape and in the sea, by not (in words he used in 2006) “banging on” about Europe and in scarcely mentioning foreign policy.

The Conservative strategy in Con-LD districts was evidently to make the election a binary choice, to argue that the Conservatives’ Cameron was a safe and unobjectionable choice that Labour’s Ed Miliband’s economic redistributionism and his apparent dependence on the even more leftish and exotic Scots Nats made him unacceptable. The constituency service work and personal relationships built up by Lib Dem MPs over the years (back to the 1980s in some cases) did not matter. The greater southwest accounted for most of the 57 seats Lib Dems won in 2010. None are left now, unless you count one district in southwest London. Even Bath, where the incumbent’s victory over the up-and-coming Conservative cabinet minister Chris Patten in 1992 made national news, went Conservative by a 38 to 30 percent margin. It’s hard to see how Lib Dems can reconstruct what took them 30 years to construct. David Cameron was willing to work with them, often constructively. But he was also willing to wipe them out, and did.

As I have written several times, the British are experienced tactical voters. They know the balance between the parties in their constituencies and cast their votes in a way to achieve the national balance in Parliament they want. That is plain in the parties’ percentages of the vote in the Con-LD and Lab-LD seats: in the former Labour won only 11 percent of the votes and in the latter Conservatives won only 15 percent of the votes. Voters who didn’t want a Conservative government in the former or a Labour government in the latter gravitated to the Lib Dems.

These were districts with Lib Dem incumbents* who in most cases were running for another term; the incumbents had worked their districts hard and built up networks of Lib Dem supporters. Even so, they were massively outvoted, 41-30 in Con-LD seats, 43-27 in Lab-LD seats. After four years of supporting a Conservative-led coalition, the Lib Dems’ previous constituency was splintering. But contrary to expectations, it didn’t move largely to Labour. Instead, previous Lib Dem voters who were reasonably satisfied with the coalition record and/or appalled at the idea of a Labour government tugged left by the Scot Nats migrated into Conservative ranks.

The implosion of the Lib Dems is plainest in the 81 marginal Con-Lab seats. Here, where there was no incentive for tactical third-party voting, the Lib Dems were reduced to an average of 4 percent of the vote, roughly comparable to the Greens. And well below the 12 percent of the vote that went to Ukip, a percentage virtually identical to the 13 percent Ukip won nationally. I speculated that the Ukip vote may have evaporated in these districts. Not so: the Lib Dem vote did. I think — and perhaps Britain’s chastened pollsters may check on this — that there was a larger Lib Dem vote movement to Conservatives than to Labour and that some Lib Dem voters whom everyone considered likely to switch to Labour voted Ukip instead. The fact that Ukip ran second in many safe Labor seats in the North of England fortifies this view: for downscale voters repelled by Conservatives but untrusting of Labour, Ukip provided a means of expressing their views. Certainly the fact that Conservatives averaged 44 percent in these 81 seats to Labour’s 36 percent, and the fact that Conservatives came out ahead 71-10 in these seats rather than the projected 44-37 behind, point to this conclusion.

Conservatives, led by Australian campaign guru Lynton Crosby and assisted by 2012 Obama campaign manager Jim Messina, clearly did a brilliant job of pounding their messages home in the seats where it mattered, gearing them to local opinion or local factors when appropriate, but stressing national themes as well. It was generally agreed that Labour had more campaigners on the ground, but they relied on a single national message with no local references, and their efforts were unable to deliver the votes they needed and which the pre-election polls suggested they would have.

4. A look toward the future.

The next election, unless the five-year term act of 2011 is repealed or its stringent conditions for another election within that interval are met, will be in 2020, a long time from now. It’s impossible to know what the economy will look like at that time, what foreign policy will look like, how the new Labour leader will fare with the public or, given that David Cameron has said he will not lead his party in a third election, who the Conservative prime minister will be.

That said, there are two factors likely to strengthen Conservatives. One is the redrawing of the constituency boundaries. Lib Dems reneged on their promise to support new boundaries after Conservatives withdrew their House of Lords reform bill from the floor of the House of Commons because of backbench opposition. (I was in Westminster Palace that day: an electric moment.) The new boundaries will clearly help Conservatives, many of whose constituencies have been growing in population, while heavily Labour seats in the North of England (and SNP seats in Scotland) have been losing population. If this election were held along the new boundaries, according to a UK Polling Report http://ukpollingreport.co.uk/blog/archives/9413 estimate, Conservatives would have won 322 of a reduced number of 600 seats. That would mean they would be ahead of all other parties (with the Speaker not voting) 322-277, in contrast to their current lead, with 650 seats, of 331-318. A 45-seat margin looks a lot more comfortable than a 13-seat margin.

A second factor is that Conservatives are not likely to be under threat from the Lib Dems. This year they were basically wiped out wherever they didn’t have incumbents, and they have only eight incumbents now. I don’t see how they can recover anything like their previous standing (23 percent of the popular vote and 57 seats) given their pathetic 4 percent average showing in seriously contested Con-Lab seats. Conservatives were the clear winners from their demise, picking up 27 of their seats to only 12 for Labour; almost all of these are likely to be solid Conservative seats looking ahead.

Nor, at least in this election, was Ukip a significant net negative for Conservatives. Instead, Ukip showed up as a competitor for Labour in many of its once solid seats. The Ukip candidate received 16.5 percent in Moreton & Outwood, the seat where Ed Balls was beaten by a Conservative by a 38.9 to 38.0 percent margin. My bet — though not one I’m certain of — is that without Ukip Balls would have won.

5. Were the polls wrong?

That’s a little like asking whether Custer lost at Little Big Horn. The pre-election polls showed little change throughout the post-March 30 election period and the consensus forecast was that the popular vote would be 34 percent Conservatives, 33 percent Labour, 8 percent Lib Dem and 13 percent Ukip. The last two numbers were about right; the first two were significantly wrong.

British polls were famously wrong also in the 1992 election, in which pre-election polls showed the popular vote for the two major parties even, but which the final results were Conservatives 43 percent and Labour 35 percent — a 7.5 percent error. The explanation generally given is summed up in the two words “shy Tories” — some Conservative voters were evidently unwilling to tell voters they were going to vote that way but in the privacy of the voting booths did so.

British polling techniques were revised, but evidently not enough: 23 years later the shy Tories seem to have made another appearance. Rob Hayward, a polling expert who coined the term shy Tory, notes that polls in 2014 elections for the European Parliament, local elections, parliamentary by-elections and the Scottish independence referendum tended to understate the actual Conservative (or anti-independence) vote by about 2 percent and overstate the actual Labour (or independence) vote by about 2 percent. If you substitute 3 percent for 2, that pretty much explains the result: the pre-election polls 34-33 race becomes in the actual vote a 37-30 race. Why? Perhaps shy Tories again.

Many Conservatives in Britain and conservatives in America suggest that in the left-wing media environment, when harsh invective is unleashed at expressions of conservative belief, many people are unwilling to say out loud that they support the Conservative (or Republican) party. But it’s also possible that we are looking at sampling or question-framing error, with pollsters reaching Conservative voters proportionately less often than Labour or Lib Dem or Ukip voters. The American fivethirtyeight.com website, which got every state right in the 2012 U.S. presidential election but was well off the mark in the U.K., explores these issues in this post and this one.

As the website’s proprietor Nate Silver wrote on Britain’s election night, citing results not only in Britain but also in the U.S. in 2014 and Israel this year, “The world may have a polling problem.” Pollsters in Britain conduct interviews on the telephone and on the Internet. Perhaps they might be well advised to go back to in-person interviews, as many did when I entered the polling business with Peter Hart in 1974 and as they are now doing in Mexico. Current polling techniques were developed for countries with universal landline telephones and a population that answers the telephone. Americans and Brits no longer live in such a country; Mexicans never have.

6. The youngest member of Parliament.

Six or seven months ago, Douglas Alexander, Labour’s shadow foreign secretary, was expecting to win his fifth consecutive election in the Scottish constituency of Paisley and Renfrewshire South in the suburbs of Glasgow. He had a reasonable expectation of becoming British foreign secretary soon. But Glasgow, which a century ago considered itself “the second city of the British Empire,” voted for Scottish independence in the September 2014 referendum, and in last week’s election Alexander lost his seat by a 12-point margin to the Scottish National candidate Mhairi Black, a 20-year-old college student with strong convictions and a sharp tongue. She is the youngest member elected to Parliament since 1667.

And who was her younger predecessor? His name was Christopher Monck, whose name I ran across in research for my book Our First Revolution: The Remarkable British Upheaval That Inspired American’s Founding Fathers. As I recounted in a U.S. News blogpost ten years ago, the History of Parliament Trust’s The House of Commons 1660-1690 gives this account of him in the course of discussing young members of Parliament.

Thus the young Monck lost his voting seat in the House of Commons at age 16 after serving nearly three years as a speaking and voting member and became a non-voting member of the House of Lords until he reached his majority. Monck’s election in the county of Devon, which had a relatively large electorate, was apparently unanimous: no one presumably would run against the son of a duke who, as a general, had led his troops south from Scotland to oust the Parliamentary government and install Charles II as king in May 1660. The House of Commons 1660-1690, in an entry written by J. P. Ferris, provides more on his career:

“At the age of 13 he was returned as knight of the shire [Devon], probably without a contest, and took his seat at once, being named to a committee on 17 Jan. 1667. On 25 Oct. he was ordered by the House, with Sir Charles Berkeley I and (Sir) William Morice, to represent to the King the danger of theft and robbery on the highway, and to ask his father, as lord general, to provide a guard. On the same day, he was named to consider the charges against Mordaunt, and later in the same session he took part in the debate on the impeachment of Clarendon, urging the House to adhere to the general charges and not ‘depart from the liberties of England,’ in spite of the judges’ opinion. He was not yet 15, and thus probably the youngest Member ever to speak on the floor of the House.” Once finally seated in the Lords, he “took little part in politics, devoting himself to extravagance and pleasure . . . In 1686 he accepted the post of governor of Jamaica, though the income was only £2,500 p.a. and he was warned that he would be surrounded by spies and subject to misinterpretation, as in Whitehall and the western campaign. He left for the island on 5 Oct. 1687, red-eyed and yellow-faced from the effects of life at Court. His principal achievement was the recovery of a wrecked Spanish treasure-ship, the first successful salvage operation of modern times, which brought him in an estimated £48,000” — an enormous sum, perhaps $3 million today — “for an investment of £800. But he did not enjoy his wealth for long: drink and the climate finished him off on 6 Oct. 1688.”

Let us hope that Mhairi Brown, who has come down from Scotland to London with a more modest pedigree than Christopher Monck, has a longer parliamentary career and a much longer life ahead of her than that young man, though it seems unlikely she will accumulate anything like the amount of wealth that he momentarily amassed.

*Technically “incumbents” is inaccurate, since when Parliament was dissolved March 30 the House of Commons ceased to exist and there were no incumbents. I write “incumbents” rather than the technically more accurate “former members” or “previously elected members” because the single word is less awkward and more familiar to American readers.