FLINT, Michigan — Cynthia Marks started boiling her water about a year ago, when government officials told her to do so. She isn’t sure if something’s wrong with it now. She doesn’t trust it. She doesn’t trust them either.

She’s got a child at home, a 13-year-old. She can’t take chances.

There’s lead in the water here, a lot in some parts of the city. So much that officials are wondering if it might overwhelm the filters handed out by the National Guardsmen who’ve been called here.

The water of the Flint River was so polluted and acidic that it ate away at the lead pipes carrying water to the city’s homes, leaching it into glasses and cups that quenched the thirst of babies and adults alike.

People shouldn’t drink it. Some folks can’t bathe in it. Clothes get ruined when they go in the wash.

And like so many other Flintites, Marks is afraid.

“It’s almost like a Third World country. Just like people bring them water, people are bringing us water,” she said. “It’s sad. Flint is really small. It’s not really a bad place.”

It’s a Tuesday afternoon at Fire Station 3, just a little north of downtown. In a gray sky, snow swirls in the biting wind and the men and women of this once-proud town bow their heads against the cold. They fight through the slog of another winter’s day and try to avoid the gaze of soldiers who hand them cases of clean water to take home to their families.

This is a place where people once rarely hung their heads for anything. This was the home of General Motors, “Vehicle City” as one of the arches over Saginaw Street proudly proclaims. There were good schools, safe neighborhoods. There was going to be a better future.

Immediately after the city of Flint began using water from the river, residents noticed something wrong and began complaining to city officials about the color and the smell. (AP Photo)

That’s all gone now. Flint’s back broke when GM moved out of town, taking with it nine-tenths of the jobs it supplied. But Flint always had its pride.

Now that too is finally broken. “I wasn’t afraid to live here, but I am now,” Marks said.

She’s a lifelong resident and she could stomach crime, dwindling city services, watching the economy collapse.

But not even having clean water? That’s just too much.

“You know, it’s water. It’s bad enough the people were kind of iffy, but now it’s the water,” she said. “It’s almost like we’re in prison. We’re all in a square footage and it’s dangerous.”

The water crisis in Flint is quickly picking up steam as a national issue, both on Capitol Hill and on the campaign trail.

The Democratic National Committee announced last week former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders would debate in the eastern Michigan town on March 6 ahead of the state’s primary. On that same day, the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform held the first congressional hearing on exactly who is to blame for the crisis.

The House Committee on Energy and Commerce is investigating the governmental response to the lead water crisis as well. They’ve held multiple meetings with EPA staff about Flint and announced Friday there will be a hearing on an unspecified date in March about the crisis.

Marks said “they” were to blame. She never uttered the name of Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder, who has been ripped for the state’s slow response to the crisis. She never talked about the financial mismanagement of the city by past administrations. She never mentioned the Environmental Protection Agency, which remained silent despite knowing the drinking water in Flint was rife with lead. Even the people at the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, deemed most responsible for this tragedy, escaped being named.

It was all of them. Republicans and Democrats. Elected officials and bureaucrats. The city. The state. The feds. Government, as an institution, failed her, failed her friends, failed her family.

The House Committee on Energy and Commerce is investigating the governmental response to the lead water crisis, holding multiple meetings with EPA staff about Flint. (AP Photo/Molly Riley)

“They knew what they were doing. Why are they acting surprised?” she asked, incredulous. “They knew what would happen. Everything that’s been done has a trickle effect. Something is going to happen that’s good or bad afterward and they knew what it was.”

She shakes her head. “It was all to save a few dollars.”

Yet contemporary history of Flint shows a willingness of voters to repeatedly elect suspicious characters who bankrupted and helped lead it to ruin.

Glory days

To understand how this crisis happened, you need to understand how the state failed Flint. But first, you need to understand how Flint’s leaders failed their own residents.

And to understand that, you need to understand this: Flint used to be great.

Like so many other now-decrepit places in the Rust Belt, Flint was once on top of the world. That was mostly due to GM. General Motors, one of the jewels in the United States’ corporate crown, called this town a little north of Michigan’s Thumb home.

Flint was also the place that gave immediate credibility to the United Auto Workers, the union that would come to dominate the Great Lake State and help engineer its post-war economic boom.

In 1937, a sit-down strike at the GM plant ended after 44 days with a pay raise and the UAW suddenly becoming a force.

The decades after that strike were good to Flint. By the early 1970s, about 193,000 people called the city home.

“There was a huge sense of optimism when I was growing up, a lot of pride and a lot of confidence and a lot of optimism about the future,” said Rep. Dan Kildee, D-Mich., a Flint native now serving his hometown in Congress.

Few people in the city, with the possible exception of those in GM’s corporate offices, knew this was to be the high-water point for Flint.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, GM began to move jobs out of the state and out of the country. This would prove to be catastrophic, if not fatal, for the city.

At its peak, GM and the auto industry employed 80,000 people in Flint. Today, it’s somewhere closer to 8,000.

No Plan B

Given that it’s been decades since GM decided to move jobs out of Flint, it would be reasonable to assume city leaders would have come up with a plan for a second act.

Yet people fled in droves, taking with them the property and income tax revenues that funded the city for so long.

The population shrank to a little less than 100,000. The only people left in Flint are those who can’t afford to go somewhere else or feel duty-bound to stay in their city.

And, through all those years, city government failed to adjust. “When those revenues start to go down, you start laying people off and the quality of services starts going down,” said state Sen. Jim Ananich, a Flint native who once served as City Council president and now is the top Democrat in the state Senate.

“A lot of people start thinking, ‘Should I stay or not?’ So, a lot of people left and that makes the problem even worse.”

Administrators and mayors throughout those years tried to keep up services while honoring the pension promises they made to past unionized city workers.

Under Flint’s strong-mayor system of government that includes a City Council, the mayor and city administrators have much of the power. Democratic Mayor Woodrow Stanley, who served throughout much of the 1990s, ended up being the face of this failure to adjust.

Democratic mayors of Flint Woodrow Stanley and Don Williamson plundered infrastructure money to pay wages. (AP Photo)

Stanley was slow to downsize Flint’s governmental operations as jobs left Flint and kept city services up in order to please his voters, who re-elected him three times. Reports from the time indicate Stanley did try some financial reforms to save money, but was blocked by the Democratic-controlled City Council.

By the early 2000s, Stanley’s administration racked up a $30 million operating deficit. Amid claims of racism, Stanley lost a recall campaign in March 2002 and the city’s first emergency manager was appointed.

Despite Stanley’s record as Flint mayor, voters elected him county commissioner just two years later. By 2009, Stanley was serving Flint as one of its state representatives in the Michigan House.

After two interim mayors, Democratic Mayor Don Williamson, who had been previously convicted in business scams decades earlier, was elected mayor in Flint in 2003. By the end of 2006, an emergency manger had left Flint in the black with a $6.1 million surplus.

Williamson’s tenure saw all of that progress reverse completely. He was accused of bribing voters by giving out $20,000 from his own personal fortune at a “customer appreciation day” at his car dealership and lied about a budget surplus that year that ended up being a multimillion dollar deficit. He still won re-election in 2007.

Lawsuits against Williamson ended up costing the city millions and he ran the city into a financial abyss. In 2009, by the time he resigned for health reasons and was facing a recall campaign, the city’s general fund was $10 million in the red.

Around the same time, the city’s problems with legacy costs were coming into sharp focus.

For the most part, these promises to past unionized workers were kept as abstract thoughts. Eric Scorsone, a Michigan State University economist who studied Flint’s descent into financial calamity, said the costs of these promises came in once a year.

It wasn’t until 2008 that new state legislation turned these once-a-year payments into the guillotine blade hanging over the city’s head. That was the year the state required cities to put retiree healthcare on the balance sheet.

“You were making promises … that weren’t even being recorded,” Scorsone said. “The decision-makers wouldn’t have even known what they were committing to other than the annual payment.”

Scorsone’s research showed the city had about $775 million of unfunded liabilities for past employees in 2011, the year an emergency financial manager took over the city.

Robbing Peter to pay Paul

How did the city administrators keep the lights on, so to speak? Oftentimes, legally or illegally, Ananich said, they used the city’s Water and Sewage Fund.

Water Lead Level Comparison Graphiq

“There’s no legal way to do it other than charging the fund for something that’s allowed,” he said, “but often, they’d just overspend and then use the fund later.”

Scorsone said city leaders used the water fund as “a bank” to pay for more basic city services. This practice of robbing Peter to pay Paul helped pay for police and firefighters, whose unions refused to accept more cuts and often took the city to arbitration.

According to a state report from 2011, the city took $61 million out of the Water Supply Fund over the previous 10 years to keep the city running and took about $10 million from the Sewage Disposal Fund from 2009-11. At the same time, city leaders increased water and sewer rates 35 percent.

The state report indicates that money “was not a loan and was not expected to be repaid.”

That money could have been used to pay for infrastructure upgrades or to pay the ever-increasing rates from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. Instead, it was gone.

Even as those funds faced financial ruin, the city kept using them as an ATM. The Water Supply Fund had a $9 million deficit in 2011 and the city continued to transfer money out of that fund and into the general fund to keep basic operations going.

In total, as of June 30, 2010, the general fund owed more than $18 million to other city funds, including the city street and public improvement fund. Using that money for anything other than fixing roads or city property was a violation of state and federal law.

According to the state report, all of these accounting tricks were hidden on the city’s records as a “pooled cash account.”

By 2011, the state had had enough. Flint’s ability to run itself would be taken away once again.

Public Act 436

In Michigan, cities and other municipal governments serve at the pleasure of the state government. What the state gives, the state can also take away.

Using Public Act 4 of 2011, Snyder installed his own leader to stabilize Flint’s finances. Michigan voters were so horrified by this law allowing the installation of a unilateral ruler with near-dictatorial powers to change city services and cancel and renegotiate contracts that they voted in November 2012 to repeal it.

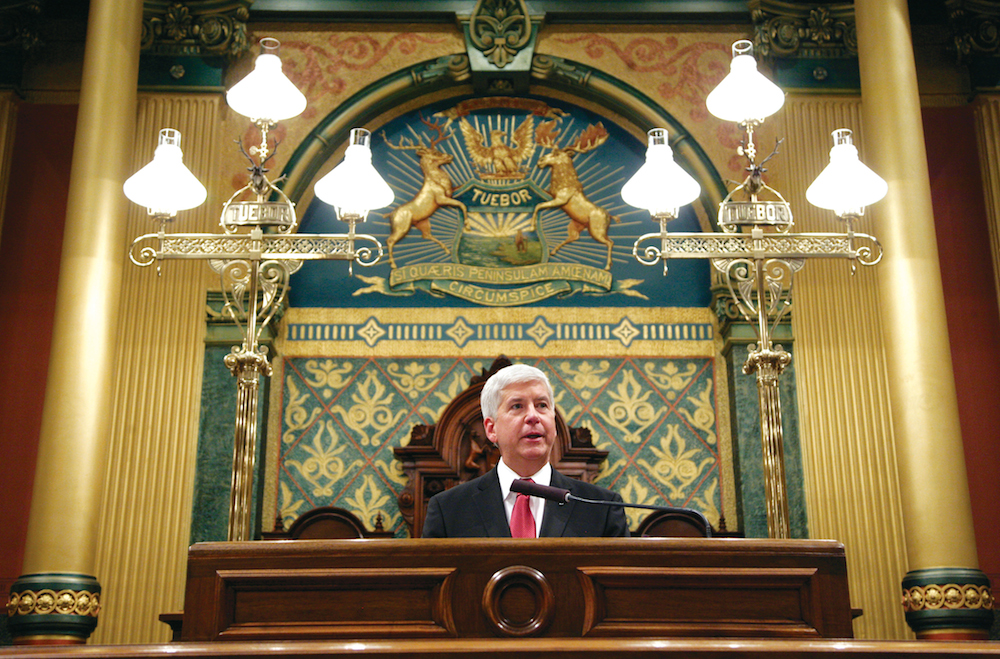

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder has been ripped for the state’s slow response to the Flint water crisis. (AP Photo)

The Republican-dominated Legislature and Snyder didn’t care much for the voters’ protests. Between the November 2012 election and the end of that year, the Legislature passed Public Act 436, a new version of the emergency manager law.

This time they included about $6 million in funding. That meant the voters couldn’t repeal the law through a referendum because the Michigan Constitution bans voters from removing laws that include any appropriation.

“The wrecking ball of Public Act 436 has hit many communities throughout the state of Michigan and not in a good way,” said state Rep. Sheldon Neeley, a Democrat from Flint and a former Flint City Councilman.

One of the purposes of Public Act 436 is to make sure governments can provide services “essential to the public health, safety and welfare” of residents, according to the law.

But, it was this law that gave Ed Kurtz, the emergency manager in charge in June 2013, the ability to unilaterally decide the city would take its water from the Flint River while waiting for the Karengondi Water Authority pipeline to be built.

Earlier that year, the Flint City Council voted to join the new authority and stop using the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department for its water source. Of course, it didn’t actually have any power to make that decision because of PA 436.

Instead, Kurtz and then-state Treasurer Andy Dillon had the final say. They signed off on the decision. It was expected to save the city about $19 million over eight years, estimates at the time showed.

Immediately after deciding to leave Detroit’s system, officials in the Motor City decided to kick Flint off their system in April 2014. It would take two years to build the pipeline to the new water authority so, in the meantime, the city would take its water from the Flint River, Kurtz decided.

When the switch actually came in April 2014, Flint residents immediately noticed something wrong. The water was brown, it smelled, it didn’t bubble up as much when they were doing dishes.

Tests showed the water was fine. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality tested water at the river and at the water treatment plant, never at homes in the city.

Of course, the pipes leaching lead into the water supply weren’t at the facility or in the river, so the problem was never caught.

The state didn’t require city workers to add any anti-corrosion controls to the Flint River water. No one has been able to explain why.

Michigan should have required the city of Flint to treat its water for corrosion-causing elements after elevated lead levels were first discovered in the city’s water a year ago, the state’s top environmental regulator says in testimony prepared for congressional hearing. (AP Photo)

“This is a case where there was a failure, in particular in the Department of Environmental Quality,” Snyder said. “Those folks work for me, so I am responsible for that and I take that responsibility.”

Flint residents were frustrated. They complained to their elected representatives on the City Council and, as elected officials tend to do, those representatives responded. Even General Motors, the company that drives Flint for better or worse, stopped using the public water system because it was corroding metal vehicles parts.

In March 2015, they voted to reconnect Flint to the Detroit water system. But, due to Public Act 436, they didn’t have any power to make the switch.

Emergency Manager Jerry Ambrose decided against switching back. It was the first act in a state response characterized by officials dragging their feet and later questioning the findings of researchers who showed them tests proving lead was poisoning the water.

It took until October for Snyder to admit something was terribly wrong in Flint. It took until January for him to declare a state of emergency. It was another example of the politics of indifference toward the state’s urban centers.

Few here will forget that a state spokesman told them as late as October that the water was safe and tests showing elevated lead levels in children’s blood were “unfortunate” in an attempt to downplay the findings.

“Everyone that was there ignored and neglected to do his or her duty to make sure this city was going to be in a living condition,” said Rev. W.J. Rideout, senior pastor at All God’s People Church in Detroit.

Anger and hopelessness

What’s happened since then has been well-documented: state and federal emergency declarations, a belated switch back to the Detroit water system, the celebrity cause du jour, millions of bottles of water coming in from all corners of the country to help.

The search for answers continues, but now has federal subpoena power. House Oversight Chairman Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, issued subpoenas last week for former Flint Emergency Manager Darnell Earley and Susan Hedman, the former head of the EPA region in charge of Flint.

The committee will depose Hedman to answer for her silencing of researcher Miguel Del Toral, who found high lead levels in Flint water in February 2015.

Earley was supposed to testify in front of the committee last week, but his lawyer refused the subpoena. Chaffetz told the U.S. Marshals to “hunt him down” to bring him before the committee, but Earley’s lawyer said that won’t be necessary.

Committee Chairman Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, chats with Ranking Member Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., on Feb. 3 before the hearing into the Flint water crisis begins. (AP Photo)

The Oversight investigation will continue. It’s possible Snyder gets hauled before the committee, which would thrill the panel’s Democrats. But, it appears there is bipartisan desire to hold everyone accountable.

“I cannot physically comprehend … what these people are going through,” Chaffetz said at the hearing, looking out on a crowd of people who traveled 14 hours by bus from Flint to D.C. for the hearing.

So, yes, Flint residents are happy that people are noticing what’s happening in their city. It’s nice to finally not be ignored. But, at the same time, these people have to go on living. They don’t even know when they can turn the water back on safely.

“The lead and all these other issues are very discouraging,” Ananich said, “but the look of complete lack of hope people have, the fear, the anger, that’s tough to deal with.”

The state is focusing its efforts now on putting phosphate into the water that will coat the lead pipes and keep them from leaching into the drinking water.

But, how can anyone trust those pipes any more? There are approximately 15,000 lead pipes in the city bringing water to private homes and businesses. In a place where the median income is about $28,000 and 35 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, how do they afford to fix those pipes?

These unanswered questions about water are only the immediate ones. When the water is drinkable again, how do you fix the loss of property tax, income tax and state funding that dried up in the last 30 years and isn’t coming back?

“This is an urban crisis zone,” said Rev. Jesse Jackson, who has been in Flint consulting with city leaders. “The water happened to be how it manifested itself, but even if you had water you’d still have unemployment, subprime lending, foreclosed housing, a diminished tax base. In many ways, the water just happens to be the point of challenge.”

Flint won’t be the last place in the richest country on the planet to experience this kind of crisis. Infrastructure all around the country is crumbling. There are lead pipes in lots of aging cities.

Ananich said politicians tend to focus on much sexier issues. Who cares about roads and pipes when the Islamic State is running rampant? But eventually infrastructure must be fixed. “We have all these issues that nobody wanted to deal with because they’re not sexy and now they’re coming home to roost,” he said.

This is an angry place right now, full of people who have been lied to and now don’t know who to trust.

In one of his most famous speeches, President Abraham Lincoln said the United States was a “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” That would be news to people like Cynthia Marks.