BINGHAMTON, New York — Folks along both sides of the state line know they’re sitting on a gold mine geologists call the Marcellus Formation, but those to the north have watched helplessly as their Pennsylvania neighbors prospered, an issue that President Trump believes could help him win the critical Keystone State on Tuesday.

The land on both sides was the same for generations, farms, fields, and woodlands dotting the bowl-shaped valley where the Susquehanna and Chenango rivers meet, and provided landowners with equal means. Then came fracking, which New York banned and Pennsylvania embraced. It minted millionaires in Pennsylvania but spread only the green associated with envy in the Empire State.

[PREDICT TUESDAY’S WINNER WITH THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER’S INTERACTIVE ELECTORAL MAP]

“Can you imagine what that must be like?” Scott Kurkoski, an attorney for the Joint Landowners Coalition, told the Washington Examiner. “To watch your neighbors get rich and you have nothing?”

Kurkoski represented some 70,000 New York landowners who thought their ships had come in back in 2007, when energy companies such as XTO Energy and Hess began offering life-changing amounts of money for oil and gas rights to their property. Scrubland that no one had wanted was on track to pull in $2,500 per acre with landowners also locking in 15% to 20% in royalties on production.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo put a moratorium on the practice in 2008. Four years later, he banned it outright, citing concerns raised by environmental activists, Hollywood celebrities, and wealthy cultural elites.

“We had those deals done and ready to go,” Kurkoski said. “We just needed the state to cooperate.”

A similar scene was playing out in western Pennsylvania, but for many, it had a much happier ending. Pennsylvania welcomed hydraulic fracturing, the process in which water, sand, and chemicals are injected into wells miles deep to break up layers of shale, releasing oil or gas.

Dan Fitzsimmons, who owns 185 acres in New York’s Broome County, watched as his neighbors just 15 miles away in Pennsylvania cashed in. He said his disappointment grew every time he saw red flares, signaling a new drill site, dot the night sky.

“Everyone’s getting rich,” another New York landowner, Victor Furman, said of his Pennsylvania neighbors. “People are making $500,000 upgrades to their $80,000 houses.”

The benefits from fracking didn’t just help Pennsylvania landowners. New well-paying jobs poured into the region, infrastructure improved, and new opportunities began to blossom from the boom.

Cabot Oil & Gas, for example, rebuilt hundreds of miles of local roads, helped build a “state of the art” hospital and library, extended new natural gas service to local communities, schools, and government buildings, helped fund new senior housing, and endowed a new technical college, geological engineer Chris Acker wrote in a 2018 blog post.

It’s hard to miss the cross-border contrast. Tom Shepstone, who operates the blog NaturalGasNow on behalf of his research firm Shepstone Management in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, said the towns of Bradford and Susquehanna have been two of Pennsylvania’s biggest success stories. But north of the state line, he said, “Chemung is one of the hardest hit on the New York side, and Elmira is an absolute basket case.”

Still, some fracking concerns linger.

A blistering 243-page report on the state’s 12-year run with fracking claimed public health and the environment had suffered, in part due to a “culture of inadequate oversight.” Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro faulted the Department of Environmental Protection’s leadership for being “too cozy” with the fracking industry and that the hands-off approach had harmed the state and its people.

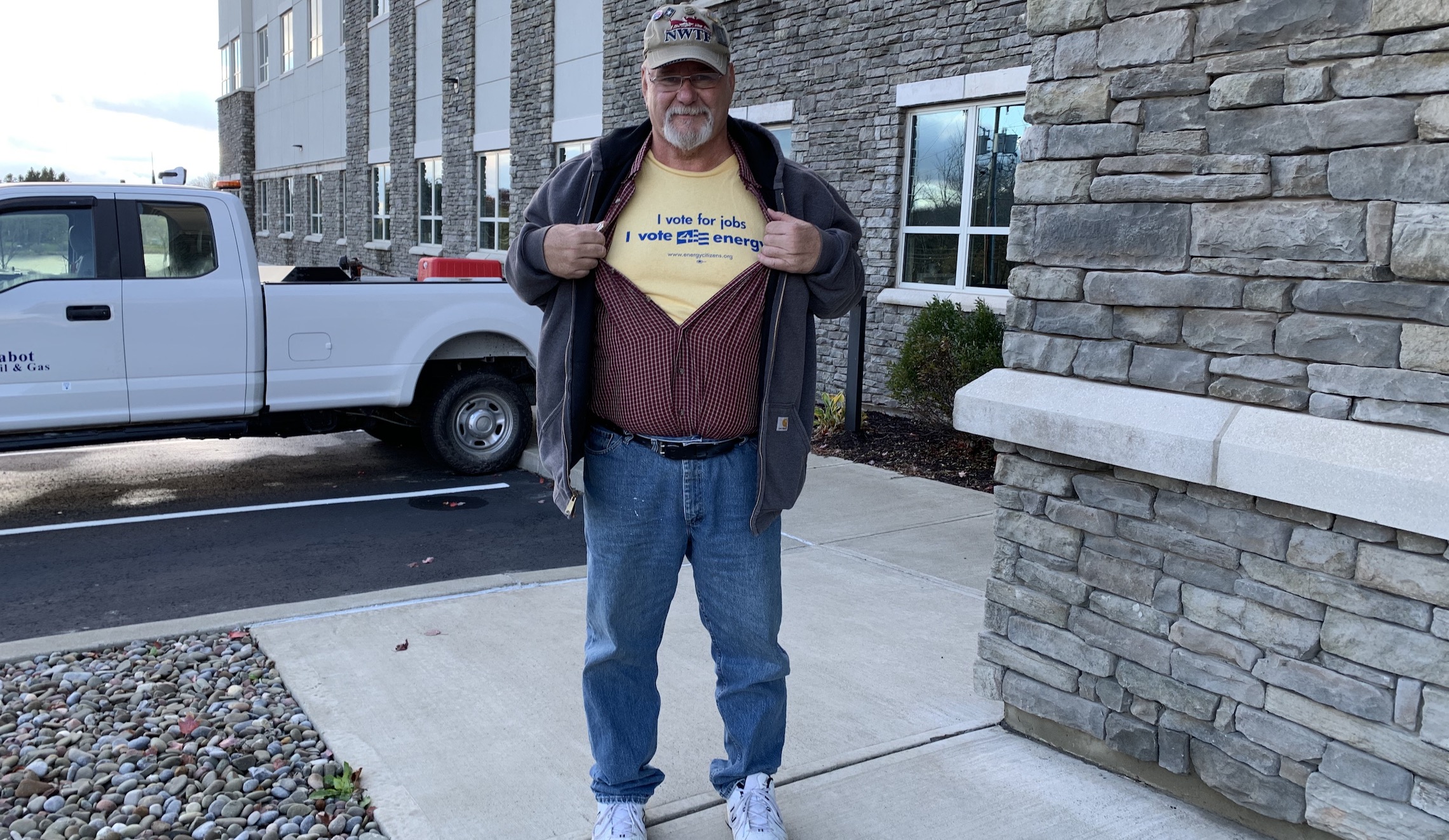

Furman, a Vietnam veteran born and raised in Binghamton, said he believes fracking should be part of the national conversation and that he’s watched with a heavy heart as opportunities dried up.

“The only thing to do around here is work in food service or at the hospital,” he said. “There’s not a lot to drive the economy.”

Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden and his running mate, Kamala Harris, have sent mixed messages about fracking, at times appearing to call for a ban, a phasing out, or perhaps just prohibiting the practice on public lands. President Trump has not equivocated in his full-throated support of fracking. Last week, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette cited Trump’s energy policies in endorsing Trump, its first backing of a Republican presidential candidate since 1972.

“Under Mr. Trump the United States achieved energy independence for the first time in the lifetimes of most of us. Where would Western Pennsylvania be without the Shell Petrochemical Complex (the ‘cracker plant’)?” the editorial board wrote.

With all eyes on Pennsylvania’s 20 electoral votes, the Trump campaign is banking on his pro-fracking stance to bolster his appeal to rural voters and help overcome the heavy Democratic vote in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

“Moments ago, I signed an executive order to protect Pennsylvania fracking and block any effort to undermine energy production in your state,” Trump told a crowd in Butler, Pennsylvania, on Saturday. “So, if one of these maniacs comes along and says, ‘End fracking,’ I signed it on the beautiful Marine One.”

No one imagines that anger over a fracking ban will put deep-blue New York in play, but in Binghamton, where a third of the population lives below the poverty line, businesses have closed, and schools have downsized, some do imagine what might have been.

“It’s frustrating to the people who are living in poverty, the towns that can’t pay for their own police departments … This was a way for them to bring in new tax revenue, and now, it’s not there,” Kurkoski said. “Here in New York, they’ve lost farms … Some have committed suicide, their families have fallen apart, their children have left, and it’s really hard to see, but that’s been the result of what’s happened.”