Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell bears responsibility for the highest inflation in decades, but private sector economists and investors also share in the blame.

Those whose livelihoods depend on making reliable forecasts and betting on markets joined Powell in failing to see in 2021 that rising inflation was not merely “transitory.”

True, a few noteworthy high-profile people warned early in 2021 that the Fed’s easy-money policies, combined with massive relief spending by congressional Democrats, would lead to too much spending economywide and push inflation too high — most notably Larry Summers, the former Clinton treasury secretary and Obama economic adviser, and Olivier Blanchard, the former International Monetary Fund chief economist. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), too, frustrated members of his party throughout 2021 by opposing further spending out of fear of inflation.

Yet the vast majority of the economics profession failed to see what was coming.

THE ONE STATISTIC THAT IS MAJOR TROUBLE FOR WHITE HOUSE ‘RECESSION’ DEFENSE

For example, there was no clear projection that inflation would remain high in the Blue Chip Economic Indicators, a collection of forecasts from business economists. As late as October 2021, the Blue Chip forecasts showed inflation ending the year at 4.3% and then dropping to 3.2% in 2022 — slightly above the Fed’s target, but only slightly, by a margin easily explained by supply chain disruptions.

Similarly, the group of professional forecasters surveyed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia expected in the third quarter of 2021 that inflation would rapidly fall back down to near the 2% target by the end of 2022.

Nor were investors in Treasury markets prepared. Yields on one-year Treasury securities were well below 1% throughout the year — meaning that buyers ended up losing significant money, in real terms, as their returns fell well short of realized inflation.

“They were all surprised, just as much as the Fed was,” said Joseph Gagnon, a fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former official at the central bank.

One reason the inflation surprised almost everyone is the unique pandemic and war-related supply chain disruptions.

“This is just a unique shock that we have never seen before and that no one was able to get on top of,” Gagnon said.

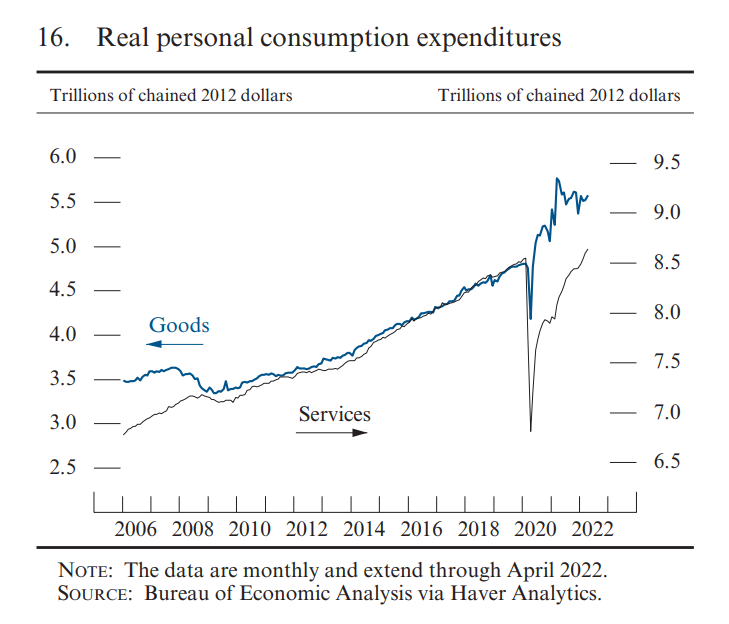

Part of the shock was a major shift in spending away from services and toward goods — spending on services remains below the pre-pandemic trend, but spending on items such as cars, appliances, sports equipment, and furniture is far above trend.

Prior to the pandemic, retailers had honed the art of maintaining very low inventories and having suppliers provide goods just in time to stock the shelves, said Susan Sterne, president and chief economist for Economic Analysis Associates. When the pandemic hit, “suddenly that was all blown apart,” she said. Consumers, many flush with relief checks from the government but stuck at home, started ordering goods online in huge quantities. At the same time, shutdowns in China and bottlenecks at ports and along transportation lines made it far higher to get goods into the United States. Energy prices soared too, all adding costs for goods.

None of that could have been foreseen.

Still, the supply-side problems created by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine cannot fully explain U.S. inflation.

GDP, in nominal (non-inflation-adjusted) terms, has risen far above the pre-crisis trend and above forecast, surging 10% in 2021 and then at a 6.6% annual rate in the first quarter of 2022. Economists view that as a sign of excess demand, rather than just supply-side problems.

How could both Powell and the private sector fail to see that the Fed was allowing monetary policy to become too loose?

Powell’s early, pre-pandemic tenure at the Fed provides a clue.

As Fed chairman, the former investment banker and lawyer had created the conditions necessary to keep the long jobs expansion intact through March 2020 — most notably by undertaking a campaign to cut the central bank’s interest rate target repeatedly throughout 2019.

Powell was effectively reversing a mistake made by the Fed under his predecessor, academic economist and current Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

Yellen spent almost her entire tenure as Fed chairwoman, which lasted from 2014 to early 2018, tightening monetary policy. Even though inflation was below the 2% target, Fed officials decided to raise rates based on what economists call the “Phillips curve” — that is, the relationship between unemployment and inflation.

To simplify, when the unemployment rate fell to 5% at the end of 2015, Yellen and company thought the economy was near full health and that inflation was bound to rise as predicted by the Phillips curve. Further monetary stimulus would only generate higher inflation.

Yellen was mistaken. She paid a political price for her mistakes when then-President Donald Trump, an unabashed and unconstrained advocate of lower interest rates at the time, replaced her in favor of Powell.

Powell soon presided over a major about-face. The Fed stopped raising rates in 2018. Then, citing low inflation expectations and fears of economic headwinds, Powell began lowering rates back down in mid-2019.

As it turns out, the labor market had much more room to grow without sparking inflation. Unemployment fell all the way to 3.5% before the pandemic, with few signs of excess inflation, much lower than the 5% Fed officials had thought possible. Jobless rates for black and Hispanic workers fell to record lows. Wage growth was accelerating.

The difference between a 5% unemployment rate and a 3.5% one is enormous. It represents about 2.5 million employed people, in terms of today’s labor market.

To avoid a repeat of the mistake of choking off job growth too early out of fear of future inflation, the Fed under Powell went so far in 2020 as to institute a new framework that explicitly allowed for the possibility of inflation rising slightly above target for a period of time to compensate.

When a similar situation arose in 2021, Powell applied the lessons of 2018-2019 and made clear he wanted to see how far job gains could go without inflation getting out of hand.

“We think we can be patient and allow the recovery to take place and allow the labor market to heal,” he said at a conference in October.

Crucially, Powell and the Fed got private-sector forecasters to buy into their line of thinking.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The Fed’s long struggle to push inflation up to 2%, and persistent misjudgment about unemployment bottoming out, led many to believe similarly in 2021 that inflation risks were low.

The experience “kind of created a certain framework or expectations of thinking of low inflation as really being something that is really built into the economy and hard to move,” said Peter Bernstein, chief economist of RCF Economic and Financial Consulting in Chicago.