“Political power,” Mao Zedong famously declared in 1938, “grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Mao’s actions matched his words. The communist theoretician founded the People’s Republic of China — and murdered millions. But political power also flows from knowledge. Spies played a key role in the rise of the PRC, from Mao’s era to our own. And their reach extends far beyond China’s shores.

On April 17, 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it was charging two defendants in connection with “opening and operating an undeclared overseas police station in lower Manhattan.”

US AND CHINA ENGAGE IN WAR OF WORDS AT SINGAPORE SUMMIT

The two people accused, Lu Jianwang and Chen Jinping, allegedly helped the PRC spy on and intimidate Chinese dissidents living on American soil. The two are charged with acting at the behest of the Fuzhou branch of China’s Ministry of Public Security and with establishing a police station that occupied an entire floor in an office building in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

The revelation that a foreign power was operating with seeming impunity inside the United States sparked both outrage and curiosity. There are more than 100 illegal police stations operating throughout the world — including at least two more in the U.S., one in Los Angeles and another at an undisclosed location, according to Safeguard Defenders, a nonprofit organization focused on pan-Asian human rights.

Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI) held a bipartisan press conference in Manhattan, in which the chairman of the newly established U.S. House select committee on China asked, “How have we allowed this to happen on American soil? The answer, in my opinion, is that we have been blind, while the CCP has been very cunning.” The U.S., Gallagher warned, risks “becoming a hunting ground for dictators.”

It is inarguable that the U.S. has been blind to the threat posed by Chinese intelligence and influence operations. Indeed, the existence of the secret police stations was first revealed by Safeguard Defenders. In 2022, the group released several reports highlighting the PRC’s “illicit methods to harass, threaten, intimidate and force targets to return to China for persecution.” Many of the stations, the reports noted, were established in 2016, a fact that rebutted Beijing’s claims that they were created as a response to the coronavirus pandemic that began in 2020.

The recent indictments offer the latest evidence of China’s intelligence gathering. Earlier this year, a Chinese spy balloon traversed the U.S. before eventually being shot down on Feb. 4, 2023. American officials later revealed that the balloon possessed the capability to geolocate electronic communications, rejecting China’s claim that it was simply a weather balloon that had blown off course. The Pentagon later acknowledged that there have been other instances of Chinese spy balloons violating the sovereignty of the U.S., as well as more than 40 countries, including American allies.

Both the spy balloon incident and the revelations of secret police stations bring welcome attention to China’s intelligence gathering. Yet Chinese communist spies are hardly new. The history of China’s spy services stretches back a hundred years and is inseparable from the founding of the Chinese communist state.

The story begins not in China but in the nascent Soviet Union.

In December 1917, a month after the overthrow of the provisional government in Russia, the founder of the Soviet Union, Vladimir Lenin, called to “set the East ablaze.” With his eye on the capitalist West, Lenin advocated exporting communism to Central Asia and eventually, he hoped, British-ruled India. But his ambitions didn’t stop with the Raj.

“Let us turn our faces towards Asia,” he declared. In 1919, Lenin established the Communist International, or Comintern, to achieve world communism.

Lenin believed that capitalism would be weakened if it were cut off from the markets and resources that its colonial and semi-colonial territories provided. Lenin’s successor, Josef Stalin, held the same beliefs. And like Lenin, Stalin thought that chaos and division were essential ingredients to a communist revolution. China offered a compelling model.

In 1911, the emperor had been overthrown and a republic declared. Peking was internationally recognized as the capital, and a quasi-government was established. Yet China was rife with internal divisions, descending into a period in which regions were ruled by competing warlords, several with foreign sponsors.

In January 1920, the Bolsheviks took Central Siberia, establishing an overland link to China. Within four months, the Comintern sent a representative, Grigori Voitinsky, to China. By May, it had established a center in Shanghai. When budding Chinese Communist Party officials held their first congress a year later, two Comintern apparatchiks were in attendance, and so, too, was a young, albeit still undistinguished, delegate from the interior province of Hunan named Mao Zedong.

By 1926, the CCP had perhaps 20,000 members, and within a year, it would triple in membership. Yet this was but a fraction of a population estimated to be around 500 million. In keeping with communist doctrine, the Soviets would aid and support their brethren in China. Yet the Soviet Union would also arm and supply other parties in China, notably the Kuomintang, an umbrella nationalist movement.

“Comintern policy,” the historian Stephen Kotkin noted, “compelled the Chinese communists to become the junior partner in a coalition with the Kuomintang in order to strengthen the latter’s role as a bulwark against imperialism.” Spying would be a key element in the communist advance.

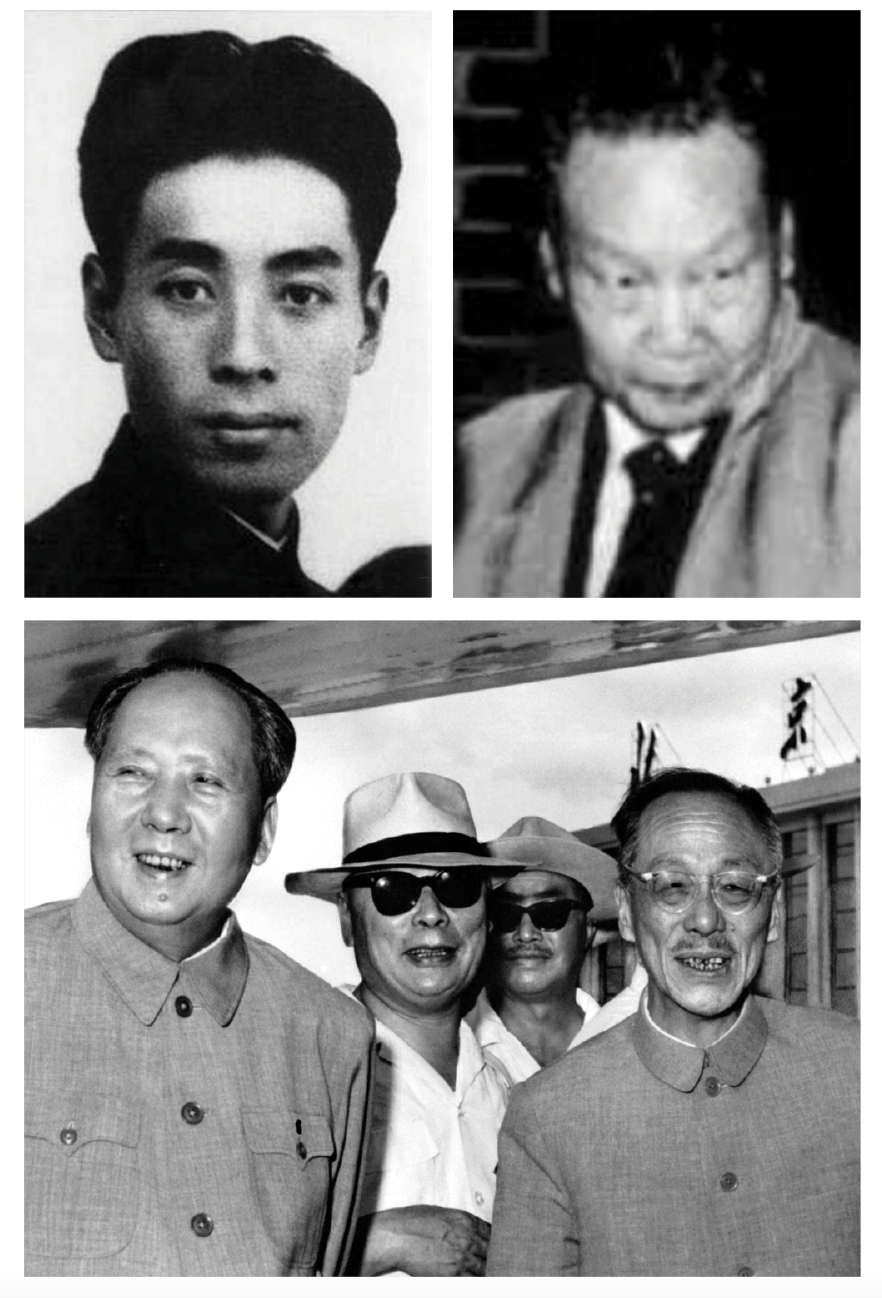

In 1927, the first Chinese communist spy service was established, the Central Committee Special Branch, or Zhongyang Teke. The Special Branch was created by Zhou Enlai, whose connections with the Comintern seem to date back to his time as a student in Germany in the early 1920s. Zhou would go on to become a founding father of the PRC and would later serve as Communist China’s premier from 1954 until his death in 1976.

The enemies of the CCP’s spy service were legion. Chinese communists had to contend with nationalists, the Japanese, and myriad foreigners who inhabited China, many of them in Shanghai, the birthplace of the CCP. The city had been carved up by foreign powers. By the time of the CCP’s founding, a mere seven of its 20 square miles were under direct Chinese rule.

In Shanghai, the British author J.G. Ballard recalled, “anything was possible, and everything could be bought and sold.” The city was a den of intrigue, replete with opium dens, cabarets, brothels, and spies. Shanghai, the author Ben Macintyre observed, “was the espionage capital of the East.” Foreigners didn’t need a passport or visa and were constrained only by the residence permits of their native countries, enabling spies to slip anonymously from one foreign-controlled jurisdiction to the other.

Shanghai would be the first proving ground for CCP spies.

By 1927, Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-Shek turned on the communists burrowed within his ranks, launching what became known as the “White Terror.” The purge ended cooperation between the CCP and the Kuomintang and resulted in thousands of deaths. “The bloodletting,” Macintyre observed, “was particularly horrendous in Shanghai.” The war between the two would continue intermittently for two decades.

Tellingly, internal enemies would be the priority for the CCP’s spies. “China’s intelligence agencies,” analyst Alex Joske wrote, “are bastions of ideological conservatism eager to see the black hand of foreign enemies” behind domestic unrest. That paranoia was ingrained from its earliest days. Intelligence operatives, with their time abroad and foreign contacts, would often fall victim to internal squabbles.

The man who could be considered the organization’s first spymaster, Gu Shunzhang, had been “born on [the] wrong side of the tracks in Shanghai” and spent his “adolescence hanging around bars, smoking opium, having affairs with women, learning the ways of the underworld,” journalist Roger Faligot noted in his book Chinese Spies: From Chairman Mao to Xi Jinping.

Gu was literally a magician, working as an illusionist and performing in the numerous nightclubs and casinos that dotted the Shanghai landscape. But Gu also worked in a tobacco plant, and it was there that he began his association with the CCP. The magician was sent to the Soviet Union for training, where he learned new parlor tricks before returning to China and linking up with Zhou.

Gu was soon named head of the CCP Politburo’s security service, where he was active in the conflict with the Kuomintang. But Gu’s magic tricks proved to have a short shelf life. It was while performing at a show in 1931 that Kuomintang’s spy service identified him from a photograph and flipped him into a double agent. Information provided by Gu reportedly led to the roundup and execution of countless communists. In 1934, the Kuomintang killed him.

Another early CCP spymaster would prove to have a much longer, and even more infamous, career. Kang Sheng would go down in history as “China’s Beria,” an allusion to Lavrentiy Beria, who served as Stalin’s spymaster. But Kang would outlive both Beria and Stalin, his days as a feared intelligence chief lasting well into the 1970s, when he continued to orchestrate purges for his longtime master, Mao. Indeed, when current CCP President Xi Jinping’s father, a founding father of the Chinese communist state, was excommunicated in the 1960s, Xi’s family blamed Kang.

Like Gu, Kang had been trained in the Soviet Union. Kang had originally been a supporter of Wang Ming, a rival of Mao. And like Gu, Kang had been a labor organizer before ascending the ranks of the CCP’s security architecture. Kang “could freeze you with a stare,” a Soviet liaison observed. “Everyone was afraid of him. You could see at first glance that he was a very evil and ruthless person.”

Suffering from both mental illness and severe myopia — his extra thick glasses, the New York Times wrote at his death, added to his “sinister appearance” — Kang spent the late 1930s and early 1940s rooting out accused spies in the CCP’s ranks, solidifying Mao’s grip on power.

Kang set up an intelligence school and headquarters at the “Date Garden,” which, Faligot noted, “soon came to be feared by CCP cadres as a horrific, nightmarish lair,” with interrogation rooms and prisons built into a clay hillside.

Kang’s job, the intelligence historian Christopher Andrew observed, “was to depose and destroy his fellow party members, and his continuing ‘investigations’ in the early 1960s laid the groundwork for the attacks of the Cultural Revolution to come.”

Kang’s own influence would ebb and flow, bolstered at times by having introduced Mao to his third wife, the former actress Jiang Qing, later known as the infamous “Madame Mao.” Kang, Faligot argued, was “the inventor of Maoism,” persecuting what he called “deviationist elements.” He would later play a key role in the Sino-Soviet split during the late 1950s, pushing for Beijing to be more independent from its onetime patron.

While the Kuomintang and the West battled the Japanese in World War II, the CCP largely stayed on the sidelines, saving its forces and energy for the renewed civil war that would follow. When the CCP won that conflict, proclaiming the establishment of the PRC in 1949, Mao’s spies had done their part. And they would play an even larger role in ensuring the survival of the Chinese communist state against enemies both foreign and domestic.

The CCP had spies abroad almost from its inception. This included Japan and other Asian nations, but the West wasn’t immune. France in the 1920s, with its many Chinese students and dissidents, was replete with budding communist agents. As the Cold War heated up, many of them would make their way to the U.S., Britain, Canada, and elsewhere. Perhaps their greatest success would be securing a mole inside the U.S. government for nearly four decades.

Larry Wu-tai Chin, a Chinese-born American, was recruited by CCP spies in 1944. He obtained employment in the U.S. Army as a translator and served in consulates in Shanghai and Hong Kong, passing state secrets the entire time. During the Korean War, he supplied Mao with the names of captured Chinese soldiers who were cooperating with American interrogators.

Next, Chin worked for the CIA, spending decades passing documents to his handlers and assisting CCP counterintelligence in catching “traitors.” His treason resulted in the murder of an untold number of CIA agents in China. Regrettably, it wouldn’t be the first time that U.S. assets in the Middle Kingdom would be compromised and extinguished.

Chin’s greatest coup, however, would be in alerting CCP leadership to President Richard Nixon’s planned overture years before it took place. When Nixon “went to China,” opening relations with the communist government more than 20 years after they were severed, the CCP was well prepared.

Mao and his premier, Zhou, were able to negotiate from a position of strength, extracting concession after concession from Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger — even though China’s own domestic situation was dire, its economy and society wrecked from Maoist initiatives.

Chin wouldn’t be caught until 1985 after a defector from the CCP revealed his treachery. He committed suicide in a Virginia jail cell while awaiting trial. Around the same time, then-CCP head Deng Xiaoping embarked on reforming and professionalizing China’s numerous spy services, even enlisting Xi Zhongxun, the father of Xi Jinping, to help.

CCP spies would have other notable successes in the U.S., famously penetrating the Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos national laboratories. They also proved adept at laying “honey traps,” in which an agent uses sex or romance to obtain information or favors, to ensnare American businessmen, politicians, and even, in one famous instance, FBI counterintelligence agents themselves.

Industrial espionage would prove to be another field that China’s spies excel at, pirating key intellectual property from the U.S. and its allies. According to FBI Director Christopher Wray, the scope and scale of Beijing’s efforts “blew me away.” The bureau, he noted in 2022, is opening a new counterintelligence investigation every 12 hours. China’s economic espionage, he warned, has grown “more brazen, more damaging than ever before.”

But Beijing’s skills extend beyond conventional spying. As Joske convincingly argued in his new book, Spies and Lies, “Influence and espionage are inextricable in the Chinese Communist Party’s intelligence operations.” An Australian-based intelligence analyst, Joske has documented the CCP’s extensive efforts to influence Western policy- and opinion-makers, including using Western think tanks to construct the intentionally disarming narrative of China’s “peaceful rise.” The CCP, its interlocutors argued, didn’t intend to threaten or supplant the U.S.-led international order. Rather, it just needed to be accommodated.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

But this was just a ruse: another deception by the descendants of Gu and Kang. And Beijing has more tricks up its sleeve. A recent U.S. national intelligence assessment warned of China’s “growing efforts to actively exploit perceived U.S. societal divisions” and “become more aggressive with their influence campaigns.”

The CCP has had a century to practice and perfect its spy craft, often catching the West flat-footed. But with a new Cold War heating up between an empowered China and the U.S., the stakes are much higher. In this new war, the West is facing a formidable foe.

Sean Durns is a Washington, D.C.-based foreign affairs analyst.