America’s power and influence are waning in its own backyard while its enemies are steadily gaining ground. And the United States has only itself to blame. Through a series of policy errors, the U.S. is ceding the dominant position in its own hemisphere. As we approach the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine, it’s worth asking if that landmark strategic declaration is a dead letter.

For most of American history, Latin America has arguably been the chief driver of U.S. foreign policy. The last eight decades or so, with a focus on Europe and later the Middle East, can be seen as exceptions to the rule.

SPYING, BOTH AT HOME AND ABROAD, HAS BEEN ESSENTIAL TO CCP POWER

On Dec. 2, 1823, President James Monroe famously declared the “American continents … are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.”

Monroe’s message, largely drafted by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, served as a bedrock American foreign policy idea for more than a century. As the historian Jay Sexton observed in his 2012 book on the subject, “Generations of Americans would proclaim that Monroe’s message embodied fundamental principles of American statecraft.”

At the time, France promised to help Spain recover its lost colonies in South America. England was determined to prevent its historic rivals from gaining ground and possibly threatening its commercial interests. The British crown offered to use its ample military means to forestall this possibility — an enticing offer considering that the U.S. didn’t have much of an army or navy at the time.

However, czarist Russia made clear that should the U.S. abandon its neutrality, St. Petersburg would aid France. The solution to the problem, Adams argued, was a statement of U.S. preeminence in its hemisphere — even if the U.S. initially lacked the means to enforce it.

For better or worse, the U.S. became increasingly intertwined in the affairs of its southern neighbors. Some actions, such as the Mexican-American War and attempts to install regimes in Nicaragua and Cuba, fostered animosity and resentment that linger to the present day and remain fodder for America’s enemies.

But intervention wasn’t purely an attempt to expand imperial holdings. In many cases, the U.S. extended its presence to prevent rival European powers from expanding theirs. Successive generations of American presidents and congresses worked, if initially slowly and imperfectly, to establish U.S. dominance in the region. Sometimes they employed covert means, quietly backing mercenaries such as William Walker, a forerunner of sorts to today’s private military companies, to seize Nicaragua briefly and attempt to take Cuba. Between 1856 and 1903, the U.S. intervened in Panama alone no less than 13 times.

The Monroe Doctrine, Sexton has noted, “was the product of the larger geopolitical context of great power expansion, rivalry, and contraction from which the American nation and empire emerged.” The U.S. chipped away at British interests in the region, often nearly coming to blows. And after Imperial Germany, Great Britain, and Italy threatened action against Venezuela over its mounting debts, President Theodore Roosevelt issued the so-called Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.

Roosevelt stated that the U.S. reserved the right to use military force in Latin America, even to keep European powers out. As his biographer Edmund Morris noted, German officials such as Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow “regarded the Monroe Doctrine as an insult, at best a hollow threat,” and Alfred von Tirpitz, Kaiser Wilhelm’s bellicose secretary of state for naval affairs, “made no secret of his desire to establish naval bases in Brazil.” The kaiser’s strategists were even working on a far-fetched “plan for the possible invasion of the United States” in which Tirpitz would “dispatch his fleet” at the first sign of hostilities, eventually seizing “‘Puerteriko’ then launching surprise attacks along the American seaboard.” Later, during World War I, German diplomats pursued an outlandish plot to have Mexico invade the U.S. to regain its lost territories.

But as U.S. power grew, so, too, did its influence in Latin America. Over three decades, every president from William McKinley to Herbert Hoover deployed troops to the region. Indeed, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s top foreign policy adviser, Sumner Welles, wasn’t an expert on the nascent Soviet Union, China, or Europe. Rather, Welles, who as undersecretary of state was thought to be the real power running the State Department, billed himself as steeped in matters relating to the Western Hemisphere.

Similarly, in the period leading up to World War II, the FBI’s first major international posting wasn’t in Europe or Asia. With Roosevelt’s approval, the FBI had more than 700 agents operating in Latin America, collecting intelligence and working to thwart Nazi and communist ambitions.

Yet America’s assertion of dominance in its hemisphere has also been a wellspring for resentment both abroad and at home. And it is the latter, as much as the former, that has steadily eroded U.S. power in the region.

There has long been a tendency, particularly pronounced on the American Left, to apologize for the history of U.S. involvement in Latin America. Some of the ills that have plagued the region, such as poverty, instability, corruption, and autocracy, have been set, often unfairly, at Washington’s doorstep. Part of this impulse led FDR, at Welles’s guidance, to push for what he called a “Good Neighbor” policy toward the region. Yet Roosevelt didn’t go nearly so far as to force the U.S. to leave Latin America. Nor did he fail to push back against encroachments by America’s enemies. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for recent decades. And we are now beginning to reap the rewards.

China, Russia, and Iran are establishing footholds in Latin America. All three countries are revisionist powers that seek to supplant the U.S.-led world order. All three are allied in their objective. And the evidence of their ambition is growing.

Indeed, on June 8, it was revealed that Beijing is operating a spy base in Cuba, a mere 90 miles from American shores. In a telling move, the Biden administration initially denied the Wall Street Journal report — only to walk back that denial less than two days later. China, officials eventually confirmed, had been running an intelligence outpost since at least 2019. This should shock and trouble the public.

For years, the West has indulged in the CCP-approved narrative that China simply wants to be an East Asian power, not to rule the world. But this is a ruse, plain and simple. China’s rulers have greater designs, and Latin America will be an important front in the Sino-American contest to come.

Indeed, there are signs that the U.S. is rapidly losing influence throughout the region.

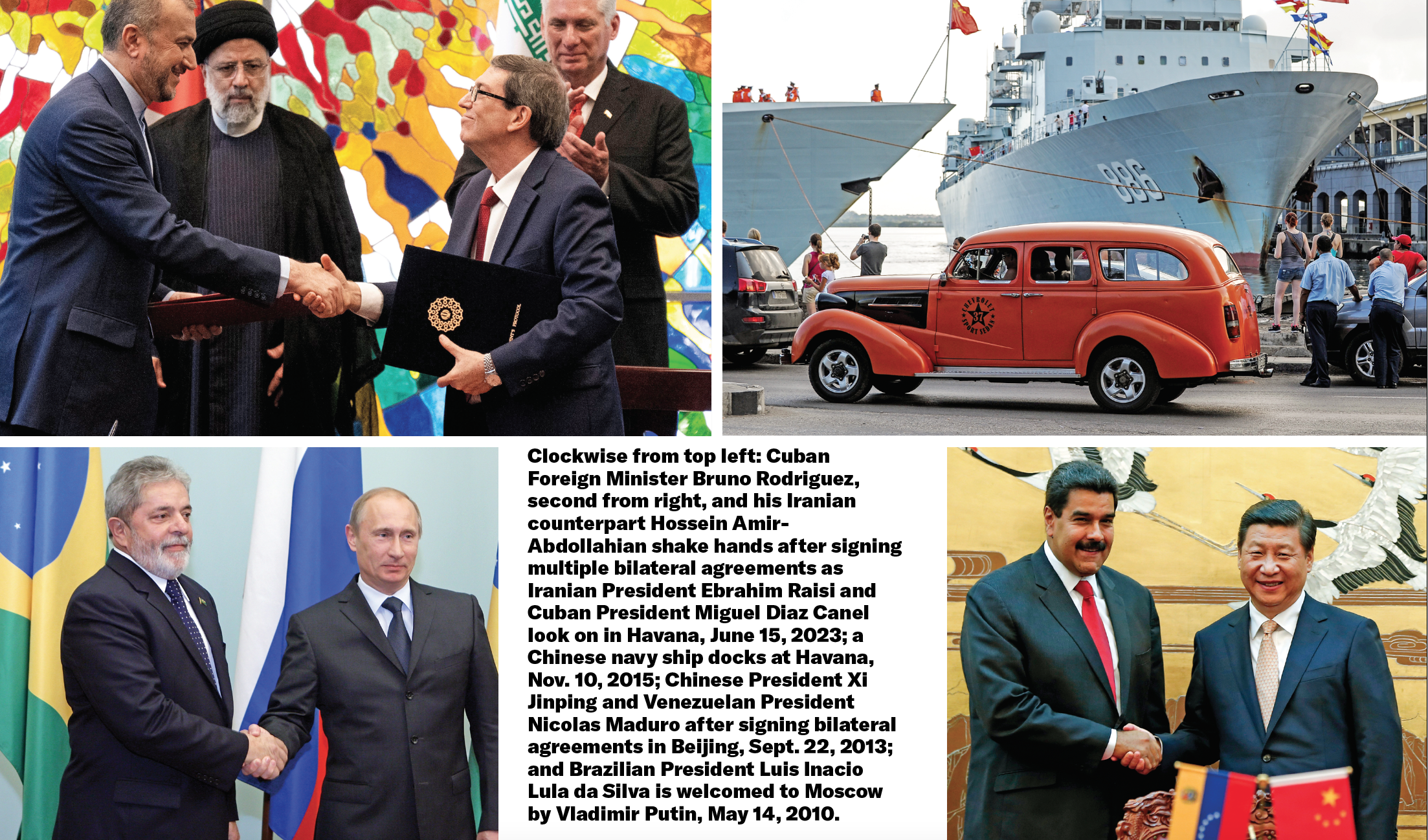

In April 2023, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, was welcomed with open arms in Beijing. A committed leftist with a long history of anti-Americanism, Lula’s 2023 return to the presidency was nonetheless hailed by the Biden administration. Yet since returning to power, Lula didn’t join President Joe Biden’s second Summit for Democracy in March 2023 and declined to sign on to its declaration condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Worse still, Lula used his China trip to call on the U.S. and the European Union to “stop encouraging war” and has steadfastly resisted efforts to send arms to Ukraine. A month after his China trip, Lula proposed creating a common South American currency to rival the U.S. dollar.

White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby told reporters that “Brazil is parroting Russian and Chinese propaganda without looking at all of the facts.” However, this is too generous by half. Lula has a history of feting America’s opponents, which is why his return to the presidency should have been lamented, not cheered.

The Islamic Republic of Iran, a key ally of Russia and China, has had close relations with authoritarian regimes in Cuba and Venezuela for decades. And Tehran’s ties in there have only grown.

In June 2023, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi embarked on a tour of Latin America, with a first stop in Venezuela. In Caracas, Raisi said Iran and Venezuela have “common interests and common enemies.” The two countries inked more than a dozen agreements, including ones that expand existing ties in the energy and military sectors. In Nicaragua, Raisi was greeted with both applause and promises to deepen trade before he proceeded to his final stop, Cuba.

Iranian, Russian, and Chinese links to Latin American autocrats aren’t new. But the brazenness in which they’re being pursued, seemingly without consequence, is noteworthy. And the lack of pushback from U.S. officials contradicts established precedence.

The deterioration in U.S. influence in Latin America didn’t happen overnight. Rather, it was the result of successive policy decisions that flowed from a particular worldview — and that marked a noticeable departure from previous U.S. aims and objectives in the region.

Under the Obama administration, the U.S. didn’t push back against its enemies in its backyard. Rather, it rewarded them. Then-President Barack Obama pushed for the most revolutionary change in Cuba policy in more than half a century. And a decade later, the results are in: It failed.

Fidel Castro’s Cuba was, of course, a key ally of the Soviet Union. It was the Castro dictatorship that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. For half a century, both Republican and Democratic administrations maintained an embargo against Cuba, which played an outsize role in exporting communism abroad and attacking U.S. interests.

Ronald Reagan and his immediate predecessors battled Cuban forces in proxy wars extending from Latin America and the Caribbean to the African continent. Reagan warned that communism presented the threat of a “new colonialism” to the region. By the 1990s, with the fall of its patron, the USSR, Cuba’s economy was in a tailspin. But defeat would soon be snatched from the jaws of victory.

The rise of another anti-American dictator and Castro ally, Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, invigorated the anti-American coalition in the region. Chavez boosted a cadre of like-minded Latin American leaders, including Lula of Brazil, the Kirchners of Argentina, Rafael Correa of Ecuador, and others. What changed, however, wasn’t the surge of the anti-American Left but the approach by the U.S., buoyed by a new president with a decidedly different outlook.

In an April 17, 2009, speech in Trinidad and Tobago, Obama apologized for the complicated history of the U.S. in the region, calling to “launch a new chapter of engagement that will be sustained throughout my administration” and proclaiming the U.S. “will be willing to acknowledge past errors.” This would be a new epoch, one in which “there is no senior partner and junior partner in our relations. There is simply engagement based on mutual respect and common interests and shared values.”

That the U.S. didn’t “share values” with the Castro or Chavez regimes was overlooked. The Obama administration believed that its enemies lacked independent aims and objectives. They merely reacted to the misbegotten policies of the U.S. Similarly, the administration, with its preference for multilateralism and disdain for hard power, glossed over another key point: Many of these regimes were continuing to aid our enemies. And autocrats don’t respect weakness. Rather, they feed off it.

Long before the CCP opened its spy base in Cuba, the island nation was providing Russia with surveillance capabilities. Nor was it just Moscow that Havana was helping. As foreign policy analysts John Suarez and Yang Jianli have documented, China has a decadeslong military presence on the island. “The dictatorships,” Suarez and Yang observed, “have much in common: They see the U.S. as an enemy, and they also see democracy and human rights as hostile to their interests. … Anti-Americanism remains a core tenet of their ideology.”

Yet the fact that Cuba had long-standing ties with Russia, China, and Iran didn’t stop the Obama administration from feting the Castro regime. Obama called to “chart a new course” in relations between Havana and Washington. Upon arriving in Cuba, the 44th president asserted that he was there to “extend the hand of friendship” and “bury the last vestige of the Cold War in the Americas.” When his plane approached Havana, Obama told his deputy national security adviser, Ben Rhodes, “That doesn’t look like a national security threat to me.”

Obama pushed to reestablish an embassy in Havana, remove the Castro regime’s well-deserved designation as a state sponsor of terrorism, and remove sanctions. Perhaps most infamously, the president of the U.S. attended a baseball game with Raul Castro, Fidel’s brother, a mass murderer and figure who played a key role in shoring up Havana’s ties with other anti-American dictatorships.

What did the U.S. get in return? Not much. Although Obama claimed that he was “under no illusion about the continued barriers to freedom that remain for ordinary Cubans,” human rights abuses in Cuba continued — and the island’s ties to hostile regimes, from Moscow to Tehran, only expanded. On June 20, the Wall Street Journal reported that China and Cuba are “negotiating a new joint military training facility that could lead to the stationing of Chinese troops 100 miles off Florida’s coast.”

The U.S. had failed to use the considerable leverage at its disposal, effectively giving away the store. Others, from Beijing to Caracas, took note.

Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed U.S.-designated terrorist group that rules Lebanon and murdered scores of Americans, has long had an extensive presence in South America, shoring up the security apparatuses in Cuba and Venezuela, carrying out attacks in Argentina, and operating a virtual fiefdom in the tri-border area of Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

According to a blockbuster 2017 Politico story by reporter Josh Meyer, the Obama administration quashed a long-running Drug Enforcement Administration investigation into Hezbollah’s extensive narcotics smuggling and money laundering, much of it in Latin America. The administration did so, the report alleged, as part of its efforts to achieve a deal with Iran over its nuclear weapons program.

Today, the U.S.-Mexico border is in chaos. Synthetic drugs, some developed with acquiescence from Chinese entities, are killing thousands of Americans. And anti-American dictatorships are expanding their influence in our own backyard. The history of the U.S. in Latin America is complicated and not without mistakes. But by forgetting that Washington has a historic interest — indeed, an obligation — to maintain the safety and security of our hemisphere, the U.S. has courted disaster. A disaster that benefits Beijing, among others, and weakens the U.S.

Sean Durns is a foreign affairs analyst based in Washington, D.C.