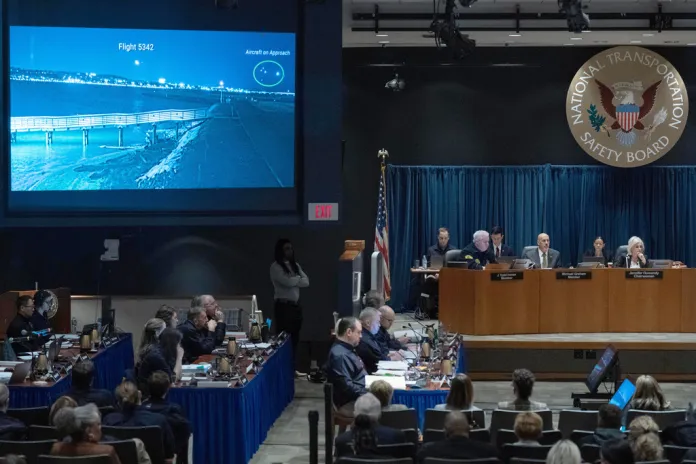

The National Transportation Safety Board on Tuesday delivered a sweeping indictment of how the Federal Aviation Administration failed for years to address known safety risks in the airspace around Reagan National Airport, setting the stage for last year’s deadly midair collision.

The collision between a U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter and a regional American Airlines jet killed all 67 people aboard both aircraft when they struck over the Potomac River just southeast of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. It was the deadliest U.S. aviation disaster since 2001.

As the board met days ahead of the one-year anniversary of the crash, investigators made clear the tragedy was not the result of a single bad decision or momentary lapse, but of repeated FAA failures to act on warning signs that accumulated for more than a decade in one of the most congested and complex airspaces in the country.

NTSB Chairwoman Jennifer Homendy said the investigation consistently returned to the same conclusion: the system drifted into danger without meaningful intervention.

“Any individual shortcomings were set up for failure by the systems around them,” Homendy said. “We are here to make sure those systems never fail again.”

How the crash unfolded

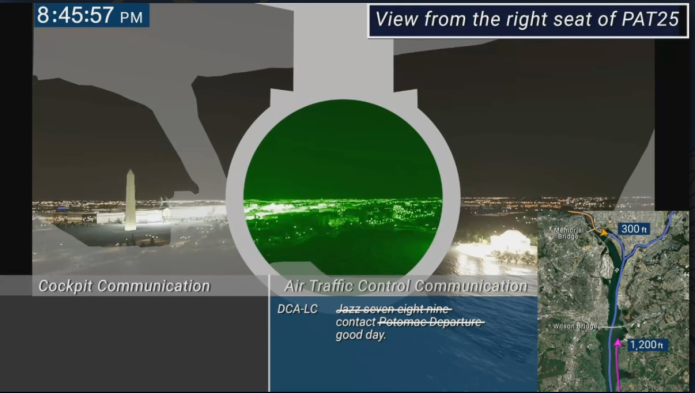

Investigators found that on the night of Jan. 29, 2025, a U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter was conducting a routine night training evaluation using night-vision goggles along a long-established route following the Potomac River, while a regional American Airlines jet was cleared to land on Runway 33 at Reagan National.

The two aircraft converged in an area where safety margins were already dangerously thin. The helicopter’s main rotor struck the underside of the airplane’s left wing, sending both aircraft into the river.

Senior accident investigator Bryce Banning told the board the pilots and air traffic controllers involved were properly trained, medically qualified, and not impaired.

“The existing separation distances between helicopter traffic and aircraft landing on Runway 33 were insufficient and posed an intolerable risk to aviation safety,” Banning said.

FAA data failures, ignored warnings, and safety culture

Much of Tuesday’s hearing focused on how the FAA handled safety data and how long-standing warning signs in the airspace around Reagan National were allowed to go unaddressed.

In one of the sharpest exchanges of the day, Dr. Jana Price, a transportation safety specialist for the NTSB, described instances where investigators said they were blocked or slowed in trying to obtain information from the FAA.

“This was in some cases, we were told that our requests were out of scope,” Price said.

Homendy pressed her on one request in particular.

“Well, in this specific request, they basically told you no,” Homendy said.

Price said investigators were initially given some information on near-midair collisions, but the numbers did not line up with what staff expected, prompting additional questions. When investigators followed up seeking more detailed safety data from a federal aviation database designed to identify collision risks, they were told the request had to go directly to the FAA’s Air Traffic Organization. Price said that request stalled as well, with the ATO declining to provide the data, citing concerns about duplicating work, even though the NTSB was asking for additional details.

Homendy said such scope disputes and delays were especially troubling during an active investigation. “It is difficult when conducting an investigation to be told what is within the scope of your investigation, telling us ‘out of scope,’” she said.

Investigators said the data-access problems mirrored a much older failure to act. After a 2013 near-midair collision involving a helicopter and a commercial aircraft in the same corridor near Reagan National, a local helicopter working group recommended rerouting helicopter traffic away from the airport, revising altitude limits, and adding warning hot spots to aviation charts.

The FAA never implemented those recommendations.

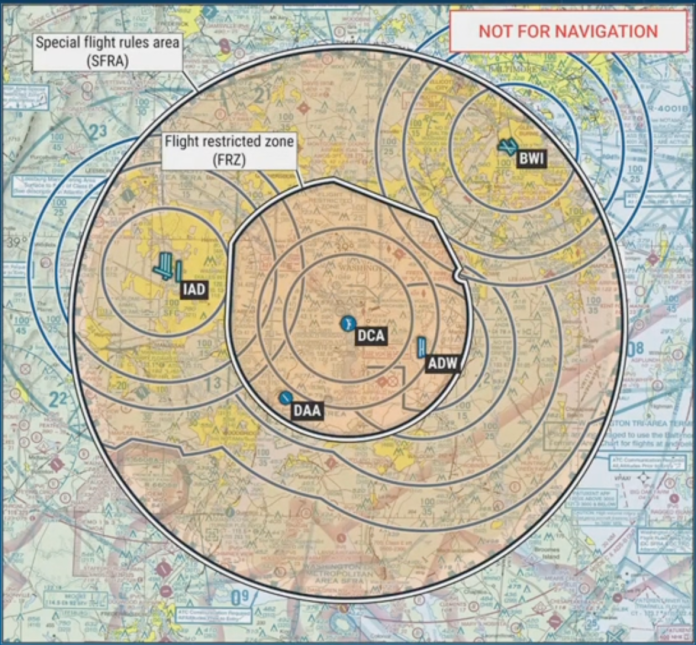

Brian Soper, who led the air traffic control portion of the investigation, said the helicopter routes were never designed to ensure safe separation from arriving and departing commercial aircraft.

“The route was never designed to ensure separation,” Soper said. “There were no procedures in place to automatically protect aircraft when operations overlapped.”

Price said those unaddressed risks continued to surface in FAA safety data for years. Multiple reporting systems captured thousands of close encounters between helicopters and commercial aircraft, but the FAA largely reviewed the events one at a time and through a compliance lens, focusing on whether rules were violated rather than whether the system itself was trending toward danger.

“The pattern was missed,” Price said.

Price also raised deeper concerns about safety culture inside the FAA’s ATO, telling the board that staff feared retaliation and that management “often discouraged filing reports because it made the facility look bad.” As a result, she said, evidence of a growing midair collision risk was never elevated or addressed at a systemwide level, even as warning signs accumulated across multiple databases.

Board member Michael Graham said the hearing revealed a troubling disconnect between the volume of safety data available to the FAA and the actions taken in response.

“I’m just amazed about the amount of data the FAA air traffic control organization had, and it sure doesn’t seem like they were doing anything with it,” Graham said.

Close calls and flight maps that never changed

Investigators said the danger near Reagan National was neither theoretical nor rare.

Since 2021 alone, there have been more than 15,200 air separation incidents involving helicopters and commercial airplanes near the airport, including 85 close-call events where aircraft came dangerously close to colliding. Those encounters were recorded across multiple FAA and industry tracking systems, yet investigators said they were never analyzed collectively in a way that triggered changes to the airspace.

Flight maps in use at the time of the crash continued to show helicopter routes running directly beneath commercial approach paths, leaving little margin for error. In some locations, helicopters flying Route 4 were separated from aircraft landing on Runway 33 by as little as 75 feet vertically.

Homendy pressed investigators on how such conditions were allowed to persist.

“As a pilot, is there anywhere in our airspace where that would ever be acceptable?” she asked.

Investigators said the answer was no.

Air traffic control workload and a missed alert

Investigators also concluded that air traffic control actions fell short in the moments before the collision. The NTSB said the controller should have issued a safety alert as the two aircraft converged, which “may have allowed action to be taken to avert the collision.”

Testimony showed that the controller on duty was operating in an unusually demanding environment, managing multiple aircraft at once in some of the most constrained airspace in the country. With helicopter and local control positions combined, the controller was responsible for overseeing both commercial arrivals and helicopter traffic simultaneously during a busy period, increasing workload and cognitive strain.

NTSB staff said the controller later indicated feeling overwhelmed as traffic levels increased and tasks competed for attention, a condition investigators said reduced situational awareness at a critical moment.

The hearing detailed an operating environment at Reagan National that routinely forces controllers to manage dense commercial operations alongside frequent helicopter flights, narrow arrival corridors, and layers of restricted and prohibited airspace. Despite that complexity, the facility was downgraded in 2018, making it harder to recruit and retain experienced controllers in a high-cost region.

On the night of the crash, investigators said the combined positions required the controller to track several aircraft in proximity while relying heavily on pilot-applied visual separation.

Dr. Katherine Wilson, a senior human performance investigator for the NTSB, said that reliance was especially problematic under those conditions.

“That expectation wasn’t necessarily valid,” Wilson said, citing high workload, divided attention, and limited visual cues.

Technology limits that could not offset bad design

Investigators also took a close look at surveillance and collision-avoidance technology and made clear the crash was not the result of a single system failing.

Much of the discussion focused on Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast. While ADS-B Out is required for most civilian aircraft, military helicopters are not always required to transmit it during training flights conducted under visual flight rules. Investigators found that the Army helicopter was not consistently broadcasting position data that could have improved situational awareness in the busy airspace around Reagan National.

Even so, the NTSB said the lack of ADS-B Out was not, by itself, the cause of the collision. Air traffic controllers could still see both aircraft on radar, and the regional jet was not equipped with ADS-B In, meaning additional broadcast traffic information would not have reached the flight crew.

Investigators did flag broader problems with how ADS-B was handled across Army helicopter operations. They said post-installation checks and routine inspections were not strong enough to catch helicopters that were not broadcasting correctly, and that Army procedures limiting ADS-B use during routine flights further reduced helicopter visibility in already crowded airspace.

The board also found that collision-avoidance systems were never meant to act as a last-ditch safety net in airspace this tight. Warning systems are intentionally limited at low altitudes, making them far less effective when helicopters and commercial jets operate close together near an airport.

The bottom line, investigators said, was that no amount of technology could make up for airspace designed with so little room for error.

Government responsibility and what comes next

The findings come as the federal government has already acknowledged its role in the tragedy. The government also acknowledged that the pilots of both aircraft failed to maintain vigilance to see and avoid each other.

Homendy said that acknowledgment does not close the book.

“When you find human error, that’s not the end of the investigation,” she said. “That’s the beginning.”

The board is expected to vote on its final safety recommendations later Tuesday, after the conclusion of the daylong hearing.

“Our work doesn’t end today,” Homendy said. “Tomorrow begins the advocacy.”

Key findings from the investigation

The investigation makes clear this crash wasn’t caused by pilot error, fatigue, or the weather, but by a series of breakdowns across the system. Both flight crews were qualified, medically fit, and doing what they were supposed to do, and both aircraft were operating as they should have been. Instead, investigators pointed to air traffic control workload and decision-making, missed or incomplete traffic advisories, and an overreliance on “see and avoid” separation in an already crowded, complex airspace.

The findings also point to deeper, long-standing problems, including risky helicopter routing near Runway 33, altimeter tolerance problems that may have left the helicopter flying higher than the crew realized, training and communication gaps, and failures by both the FAA and the Army to recognize and address known hazards. All of it added up, quietly increasing the risk of a midair collision long before this crash.