As far as elections go, 2017 wasn’t a good year for Republicans. Democrats won gubernatorial races in New Jersey and Virginia, frequently outperformed their baselines in special elections across the country and won a senate seat in Alabama—arguably the most GOP-friendly state in the country.

So what happened?

On a surface level, this is a pretty easy question. President Trump has been historically unpopular throughout his first year, and when a president polls poorly, his or her party often suffers.

But that leaves some key questions unanswered—like which voters have been showing up in 2017? Which voters have been staying home? Which voters have shifted their vote during the Trump era? And what’s going to happen in 2018?

It’s hard to conclusively answer the first three questions with publicly available data (more on this below) and it’s even harder to predict the future. But a quick review of some of the most important races of 2017 show that Republicans have some significant problems heading into 2018.

Republicans Have a Turnout Problem

Part of the GOP’s problem is that the Trump-iest voters—less well educated, often rural whites—don’t seem to be showing up in great numbers while highly enthusiastic Democrats are. This has been a common refrain among election wonks. Nate Cohn had a helpful piece on this idea after the Alabama special Senate election, and Dave Wasserman has some valuable data on how low turnout from non-college-educated whites and high turnout among college-educated whites could help Democrats in the midterms.

But it’s also worth looking at some maps and data to get a sense of how pronounced this problem is.

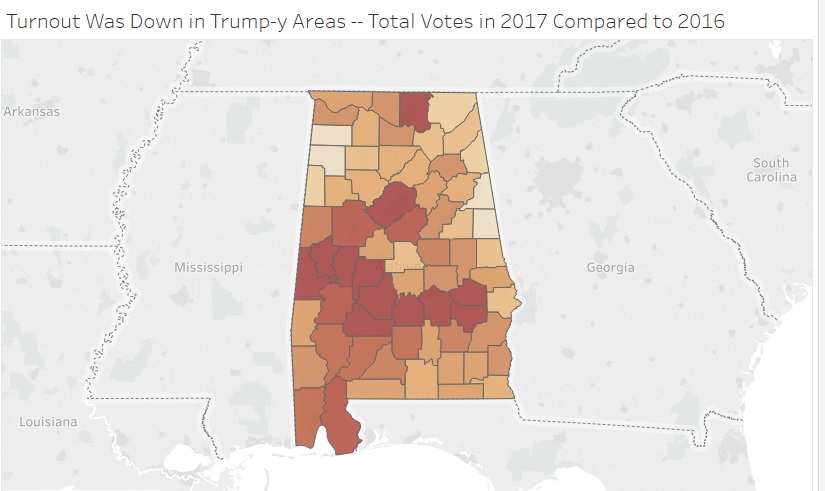

This map shows the turnout drop-off from 2016 to 2017 for each county in Alabama. Specifically, I added up the number of votes cast in each county in 2017 and divided that by the total votes cast in 2016 in that county. Darker parts of the map represent areas where 2017 turnout, compared to the 2016 baseline, was higher and lighter counties represent areas where it was lower.

If you’re familiar with Alabama politics, this map will make sense. The northern part of the state (apart from Huntsville), which is home to many rural, white, downscale, generally Trump-y voters, saw low turnout. The central band of the state, where many black voters live, and the Birmingham area saw comparatively higher turnout.

In other words, county-level data in Alabama suggest that turnout was down in some of the Trump-iest areas of the state (note: I use the word “suggest” here because county-level totals can’t tell us which individuals did or didn’t show up in an election—results obtained this way should be looked at cautiously).

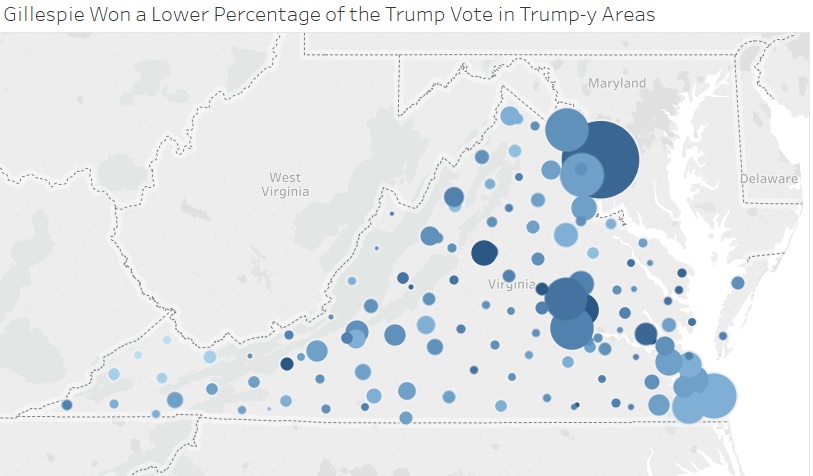

The GOP’s turnout problems aren’t limited to Alabama. In Virginia, the areas that are typically most associated with Trump—rural areas with numerous white voters without college degrees—saw lower turnout.

This map compares Republican gubernatorial candidate Ed Gillespie’s vote total compared to Trump’s total. Darker blues represent areas where Gillespie’s 2017 vote total came closer to Trump’s, and bubbles are sized based on the total turnout in that area in 2017. In short, Gillespie got a smaller share of the Trump vote in more rural, stereotypically Trump-y areas.

This isn’t the only way to document this shift. Seth Masket and Patrick Ruffini drew trends using the county-level data. In November, I broke down the data by CBSA division (rural, small town, large city, etc.) and found a similar pattern. But no matter how you slice up the data, it’s not unreasonable to look at this and think that Trump voters might not be energized in the way that Democrats are.

There are always exceptions to these patterns. In New Jersey, both county and unofficial town level results didn’t show the same clear relationship between higher vote share for Trump and lower turnout in 2017. Black voters haven’t turned out reliably for Democrats in every special election this year. There were also contests where county-level analyses like these don’t paint as clear of a picture of how much turnout dropped off (e.g. Montana, Kansas’s 4th District).

But the data from major contests, along with the sum of evidence from less prominent contests, point to problems for the GOP.

Turnout Isn’t the GOP’s Only Issue

It’s easy to focus on turnout after an election like Alabama, where an unlikely Democratic win was in part powered by a higher-than-usual non-presidential-election turnout among black voters. But that’s not the GOP’s only problem.

It’s hard to know exactly how many of the party’s problems are due to turnout and vote share without individual-level voter file data (which I don’t have). But it’s hard to imagine that persuasion didn’t matter in at least some of these elections. As Cohn pointed out, it’s hard to explain Jones’s vote totals in some well-educated areas solely by invoking turnout—some of the same upscale white Republicans who voted against Roy Moore for chief justice of the State Supreme Court in 2012 while casting their ballot for Mitt Romney probably voted for Doug Jones again in 2017. In Kansas’s 4th Congressional District, Republican Ron Estes won a much lower share of the vote than Trump in Sedgwick County (Wichita). That may have been the product of lower GOP turnout, but some voters might have flipped to the Democratic candidate. In Virginia, Democrats outperformed their share of the vote in rural areas, small towns, larger towns as well as cities. As noted earlier, low turnout among Republicans is part of that story, but so is the longer term leftward drift of voters in large urban areas (many of whom are formerly Republican college-educated white voters).

I could go on, but the point is that the GOP’s problems might not all be issues of turnout. Without voter file data, it’s hard to figure out exactly how important turnout is relative to changes in vote share, but it’s not impossible to imagine that both mattered some of the most important contests of 2017.

Maybe most importantly, Republican problems with turnout and vote share in 2017 special elections add to the growing cloud of problems surrounding them in 2018. Numerous incumbent Republican House members are retiring. The president is unpopular. Democrats are recruiting a large number of potentially viable congressional candidates. While Republicans have some advantages (a congressional map that allows them to keep the chamber even if they lose the House popular vote, a Senate map with a lot of Democratic exposure) and there’s time for conditions to change, the data as a whole doesn’t look good for Republicans.